The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason (71 page)

Read The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason Online

Authors: Charles Freeman

Tags: #History

27, 28. However rigid the theological definitions of the church, the boundaries between paganism and Christianity remained fluid. In this mosaic from Cyprus (first half of the fourth century), the god Dionysus is presented to on-looking nymphs as “a divine child” (above; credit: Scala). Perhaps more astonishing are the representations of the Virgin Mary produced by the medieval Italian confraternities. Here the confraternity of St. Francis in Perugia shows her protecting the people from the wrath of her son, who is shooting arrows of plague to earth (left; credit: Ancient Art and Architecture Collection). In Homer’s

Iliad

, Apollo also spreads plague with his arrows, and the goddesses Hera and Athena intervene to calm his wrath.

29, 30. One of the major developments of fourth-century Christianity was the adoption of the pagan custom of celebrating God through magnificent buildings, many of them of great beauty, as the simple basilica of Santa Sabina (top) in Rome (c. 420) suggests (credit: Scala). In a lovely seventh-century mosaic in her church outside Rome (above), Saint Agnes has been transformed by her martyrdom into a Byzantine princess and set against a background of gold (credit: Scala). Two of the popes responsible for building her church (one of the most atmospheric in Rome) surround her.

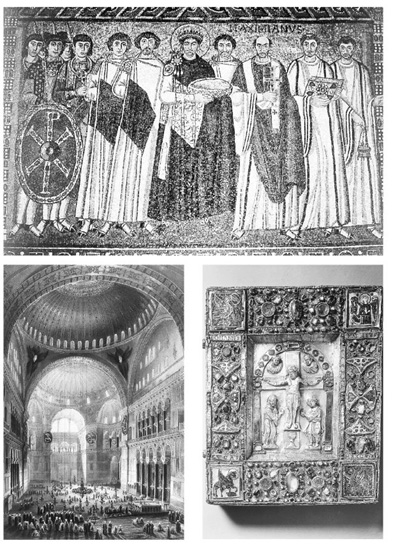

31, 32, 33. Among the most prominent church builders was the emperor Justinian (527–65), here shown with his entourage in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna (top; credit: Scala). His most majestic creation was Santa Sophia in Constantinople, here (above left) in a watercolour by Gaspard Fossati (1852, by which time it had become a mosque; credit: Scala). The massive transfer of resources into buildings was justified by Christians on the Platonic grounds that they provided an image on earth of the splendours of heaven. Any sacred object could be encased in gold and jewels, as this ninth-century gospel cover shows (above right; credit: Ancient Art and Architecture Collection). Well might Jerome complain that “parchments are dyed purple, gold is melted into lettering, manuscripts are dressed up in jewels, while Christ lies at the door naked and dying.” These underlying tensions erupted, centuries later, during the Reformation, when vast quantities of Christian art were destroyed by the reformers.

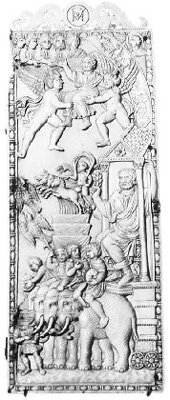

34, 35. This diptych may well have been issued by the Symmachus and Nicomachus families as a memorial to the pagan senator Praetextatus, who died in 384. “He alone,” it was said, “knew the secrets of the nature of the godhead, he alone had the intelligence to apprehend the divine and the ability to expound it.” Here a wealth of traditional imagery suggests the resilience of paganism in the late fourth century. See chapter 15 for detailed discussion of the diptych. (Credit: Hirmer)

36. The death of Symmachus, the upholder of freedom of thought against Ambrose of Milan, is commemorated in traditional style in this depiction of his apotheosis (c. 402). He ascends in heroic nudity from the funeral pyre in a four-horse chariot and is then received into heaven. (Credit: Ancient Art and Architecture Collection)

CHARLES FREEMAN

The Closing of the Western Mind

Charles Freeman is the author of

The Greek Achievement

and

Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

He lives in Suffolk, England.

ALSO BY CHARLES FREEMAN

Egypt, Greece, and Rome

The Greek Achievement

The Legacy of Ancient Egypt

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, FEBRUARY 2005

Copyright © 2002 by Charles Freeman

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Freeman, Charles, [date]

The closing of the Western mind: the rise of faith and the fall of reason /

Charles Freeman.—1st American ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Civilization, Western. 2. Christianity—Influence. 3. Church and state—

Europe—History. 4. Church history—Primitive and early church, ca. 30–600.

5. Church history—Middle Ages, 600–1500. 6. Civilization, Western—Classical

influences. 7. Hellenism. 8. Europe—History—To 476. 9. Europe—

History—476–1492. 10. Europe—Intellectual life. I. Title.

CB245.F73 2003

940.1’2—dc21

2002044821

eISBN: 978-0-307-42827-1

v3.0