The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason (70 page)

Read The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason Online

Authors: Charles Freeman

Tags: #History

16. “Alexamenos worships his god.” Early Christians were ridiculed for their worship of a “god” who had suffered the humiliation of crucifixion. In this graffito of c. 200 from Rome, one Alexamenos is mocked for worshipping a donkey on a cross. (Credit: Scala)

17. Even in the fifth century, Christians themselves had inhibitions about representing Christ on the cross, as can be seen in this representation of Christ from the door of the Roman church of Santa Sabina (c. 420). (Credit: Scala)

18. An increasing stress on the sinfulness of the human race led to graphic portrayals of the appalling agonies Christ had to go through to redeem humanity. (“The Crucifixion” from the Isenheim Altar, 1515; credit: Bridgeman Art Library)

19. A further development in the medieval iconography of Jesus was to differentiate him racially from his fellow Jews and to stress their responsibility for the crucifixion by caricaturing them. Note the same differentiation of Veronica, who has just wiped Christ’s face with her veil. (

Christ Carrying the Cross

by Hieronymus Bosch, c. 1450–1516; credit: Bridgeman Art Library)

20. The motif of the Good Shepherd had been known in eastern and Greek art for over a thousand years before it was adopted for Christ, as here (c. 300; credit: Scala). Constantine is known to have erected emblems of the Good Shepherd on fountains in Constantinople, and in his

Life

Eusebius tells how his troops mourned him as their own “Good Shepherd.” This is yet another example of how Constantine manipulated images to sustain consensus between pagan and Christian.

21. Traditional imperial iconography was also adopted as a setting for Christ’s life. On the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (359) in Rome, Christ is shown in the two central panels; in the upper panel, he appears in divine majesty ruling over the cosmos (in the same pose as an emperor is shown in a relief of 310), and, in the lower, entering Jerusalem, in a format also traditionally used for the arrival of emperors (credit: Scala). There were debates in this period over the relationship between the divine and human aspects of the emperor; here they appear to have been transferred into Christian theology, a forerunner of the great theological disputes over Christ’s nature in the decades to come.

22. While Christian art often drew on pagan imagery, it also developed distinctive themes of its own. In this sixth-century ivory from Ravenna, the emphasis is on Christ as miracle worker. The four major miracles shown are (reading counter-clockwise from top left): the Cure of the Blind Man, the Cure of the Possessed Man, the Cure of the Paralytic Man and the Raising of Lazarus. Below Christ are the Three Young Men in the Burning Fiery Furnace from the Old Testament. By the fifth century miracles had become the primary way in which a Christian “holy man” could show authenticity as one favoured by God; stories of miracles pervade the lives of the saints. (Credit: Ancient Art and Architecture Collection)

23. We also find an increasing adulation of sacred objects, icons and the relics of saints. Here the bones of St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, are borne into Constantinople by the patriarch of the city and welcomed by Senate, emperor, Theodosius II, and, probably, his pious sister Pulcheria, in 421. By now Constantinople is a Christian city. An icon of Christ appears at the gate into the imperial palace (upper left) and spectators in the top row of windows of the palace swing incense burners. (Credit: Bridgeman Art Library)

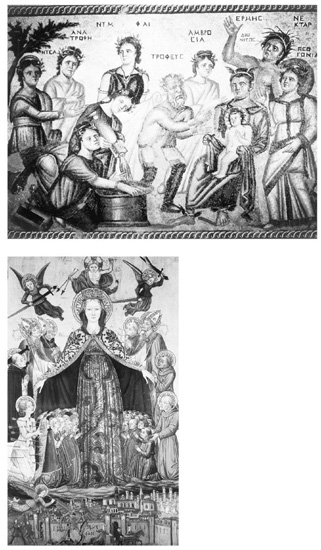

24, 25, 26. Goddesses had been prominent in Mediterranean religion, and the Egyptian Isis, here shown with her son Horus (above left; credit: Bridgeman Art Library) in a fourth-century A.D. limestone statue, was one of the most popular. As Christianity developed the role and status of Mary, she absorbed many of the attributes and iconographies of these goddesses. By the sixth century the Virgin and child, often accompanied by saints and angels, as in this example from St. Catherine’s, Sinai (above right; credit: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin /Preussicher Kulturbesitz / Museum für Spatantlike und Byzantinische Kunst), is an integral part of Christianity. No one depicts the femininity, and motherhood, of Mary more exquisitely than Caravaggio (1571–1610), here in his

Rest on the Flight into Egypt

(detail, below; Ancient Art and Architecture Collection).