The Code Book (39 page)

Figure 59

Alice Kober. (

photo credit 5.5

)

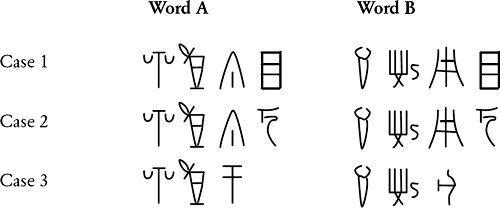

In order to crack Linear B, Kober realized that she would have to abandon all preconceptions. She focused on nothing else but the structure of the overall script and the construction of individual words. In particular, she noticed that certain words formed triplets, inasmuch as they seemed to be the same word reappearing in three slightly varied forms. Within a word triplet, the stems were identical but there were three possible endings. She concluded that Linear B represented a highly inflective language, meaning that word endings are changed in order to reflect gender, tense, case and so on. English is slightly inflective because, for example, we say “I decipher, you decipher, he deciphers”—in the third person the verb takes an “s.” However, older languages tend to be much more rigid and extreme in their use of such endings. Kober published a paper in which she described the inflective nature of two particular groups of words, as shown in

Table 17

, each group retaining its respective stems, while taking on different endings according to three different cases.

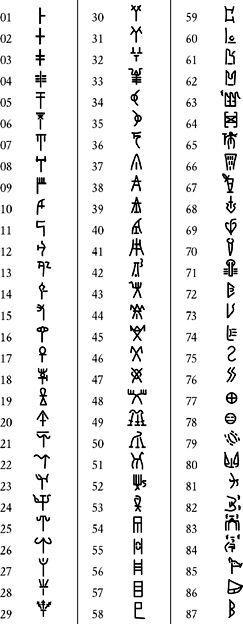

For ease of discussion, each Linear B symbol was assigned a two-digit number, as shown in

Table 18

. Using these numbers, the words in

Table 17

can be rewritten as in

Table 19

. Both groups of words could be nouns changing their ending according to their case-case 1 could be nominative, case 2 accusative, and case 3 dative, for example. It is clear that the first two signs in both groups of words (25-67- and 70-52-) are both stems, as they are repeated regardless of the case. However, the third sign is somewhat more puzzling. If the third sign is part of the stem, then for a given word it should remain constant, regardless of the case, but this does not happen. In word A the third sign is 37 for cases 1 and 2, but 05 for case 3. In word B the third sign is 41 for cases 1 and 2, but 12 for case 3. Alternatively if the third sign is not part of the stem, perhaps it is part of the ending, but this possibility is equally problematic. For a given case the ending should be the same regardless of the word, but for cases 1 and 2 the third sign is 37 in word A, but 41 in word B, and for case 3 the third sign is 05 in word A, but 12 in word B.

Table 17

Two inflective words in Linear B.

Table 18

Linear B signs and the numbers assigned to them.

The third signs defied expectations because they did not seem to be part of the stem or the ending. Kober resolved the paradox by invoking the theory that every sign represents a syllable, presumably a combination of a consonant followed by a vowel. She proposed that the third syllable could be a bridging syllable, representing part of the stem and part of the ending. The consonant could contribute to the stem, and the vowel to the ending. To illustrate her theory, she gave an example from the Akkadian language, which also has bridging syllables and which is highly inflective.

Sadanu

is a case 1 Akkadian noun, which changes to

sadani

in the second case and

sadu

in the third case (

Table 20

). It is clear that the three words consist of a stem, sad-, and an ending, -anu (case 1), -ani (case 2), or -u (case 3), with -da-, -da- or -du as the bridging syllable. The bridging syllable is the same in cases 1 and 2, but different in case 3. This is exactly the pattern observed in the Linear B words-the third sign in each of Kober’s Linear B words must be a bridging syllable.

Table 19

The two inflective Linear B words rewritten in numbers.

| | Word A | Word B |

| Case 1 | 25-67-37-57 | 70-52-41-57 |

| Case 2 | 25-67-37-36 | 70-52-41-36 |

| Case 3 | 25-67-05 | 70-52-12 |

Merely identifying the inflective nature of Linear B and the existence of bridging syllables meant that Kober had progressed further than anybody else in deciphering the Minoan script, and yet this was just the beginning. She was about to make an even greater deduction. In the Akkadian example, the bridging syllable changes from

-da-

to

-du

, but the consonant is the same in both syllables. Similarly, the Linear B syllables 37 and 05 in word A must share the same consonant, as must syllables 41 and 12 in word B. For the first time since Evans had discovered Linear B, facts were beginning to emerge about the phonetics of the characters. Kober could also establish another set of relationships among the characters. It is clear that Linear B words A and B in case 1 should have the same ending. However, the bridging syllable changes from 37 to 41. This implies that signs 37 and 41 represent syllables with different consonants but identical vowels. This would explain why the signs are different, while maintaining the same ending for both words. Similarly for the case 3 nouns, the syllables 05 and 12 will have a common vowel but different consonants.

Kober was not able to pinpoint exactly which vowel is common to 05 and 12, and to 37 and 41; similarly, she could not identify exactly which consonant is common to 37 and 05, and which to 41 and 12. However, regardless of their absolute phonetic values, she had established rigorous relationships between certain characters. She summarized her results in the form of a grid, as in

Table 21

. What this is saying is that Kober had no idea which syllable was represented by sign 37, but she knew that its consonant was shared with sign 05 and its vowel with sign 41. Similarly, she had no idea which syllable was represented by sign 12, but knew that its consonant was shared with sign 41 and its vowel with sign 05. She applied her method to other words, eventually constructing a grid of ten signs, two vowels wide and five consonants deep. It is quite possible that Kober would have taken the next crucial step in decipherment, and could even have cracked the entire script. However, she did not live long enough to exploit the repercussions of her work. In 1950, at the age of forty-three, she died of lung cancer.

Table 20

Bridging syllables in the Akkadian noun

sadanu

.

| Case 1 | sa-da-nu |

| Case 2 | sa-da-ni |

| Case 3 | sa-du |

A Frivolous Digression

Just a few months before she died, Alice Kober received a letter from Michael Ventris, an English architect who had been fascinated by Linear B ever since he was a child. Ventris was born on July 12, 1922, the son of an English Army officer and his half-Polish wife. His mother was largely responsible for encouraging an interest in archaeology, regularly escorting him to the British Museum where he could marvel at the wonders of the ancient world. Michael was a bright child, with an especially prodigious talent for languages. When he began his schooling he went to Gstaad in Switzerland, and became fluent in French and German. Then, at the age of six, he taught himself Polish.

Like Jean-François Champollion, Ventris developed an early love of ancient scripts. At the age of seven he studied a book on Egyptian hieroglyphics, an impressive achievement for one so young, particularly as the book was written in German. This interest in the writings of ancient civilizations continued throughout his childhood. In 1936, at the age of fourteen, it was further ignited when he attended a lecture given by Sir Arthur Evans, the discoverer of Linear B. The young Ventris learned about the Minoan civilization and the mystery of Linear B, and promised himself that he would decipher the script. That day an obsession was born that remained with Ventris throughout his short but brilliant life.

Table 21

Kober’s grid for relationships between Linear B characters.

| | Vowel 1 | Vowel 2 |

| Consonant I | 37 | 05 |

| Consonant II | 41 | 12 |

At the age of just eighteen, he summarized his initial thoughts on Linear B in an article that was subsequently published in the highly respected

American Journal of Archaeology

. When he submitted the article, he had been careful to withhold his age from the journal’s editors for fear of not being taken seriously. His article very much supported Sir Arthur’s criticism of the Greek hypothesis, stating that “The theory that Minoan could be Greek is based of course upon a deliberate disregard for historical plausibility.” His own belief was that Linear B was related to Etruscan, a reasonable standpoint because there was evidence that the Etruscans had come from the Aegean before settling in Italy. Although his article made no stab at decipherment, he confidently concluded: “It can be done.”

Ventris became an architect rather than a professional archaeologist, but remained passionate about Linear B, devoting all of his spare time to studying every aspect of the script. When he heard about Alice Kober’s work, he was keen to learn about her breakthrough, and he wrote to her asking for more details. Although she died before she could reply, her ideas lived on in her publications, and Ventris studied them meticulously. He fully appreciated the power of Kober’s grid, and attempted to find new words with shared stems and bridging syllables. He extended her grid to include these new signs, encompassing other vowels and consonants. Then, after a year of intense study, he noticed something peculiar-something that seemed to suggest an exception to the rule that all Linear B signs are syllables.

It had been generally agreed that each Linear B sign represented a combination of a consonant with a vowel (CV), and hence spelling would require a word to be broken up into CV components. For example, the English word minute would be spelled as mi-nu-te, a series of three CV syllables. However, many words do not divide conveniently into CV syllables. For example, if we break the word “visible” into pairs of letters we get vi-si-bl-e, which is problematic because it does not consist of a simple series of CV syllables: there is a double-consonant syllable and a spare -e at the end. Ventris assumed that the Minoans overcame this problem by inserting a silent i to create a cosmetic -bi- syllable, so that the word can now be written as vi-si-bi-le, which is a combination of CV syllables.

However, the word invisible remains problematic. Once again it is necessary to insert silent vowels, this time after the n and the b, turning them into CV syllables. Furthermore, it is also necessary to deal with the single vowel i at the beginning of the word: i-ni-vi-si-bi-le. The initial i cannot easily be turned into a CV syllable because inserting a silent consonant at the start of a word could easily lead to confusion. In short, Ventris concluded that there must be Linear B signs that represent single vowels, to be used in words that begin with a vowel. These signs should be easy to spot because they would appear only at the beginning of words. Ventris worked out how often each sign appears at the beginning, middle and end of any word. He observed that two particular signs, 08 and 61, were predominantly found at the beginning of words, and concluded that they did not represent syllables, but single vowels.