The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Seven (41 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Seven Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

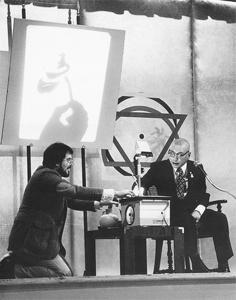

Spontaneous calligraphy on overhead projector. Los Angeles Dharma Art Seminar.

PHOTO BY ANDREA ROTH, 1980. FROM THE COLLECTION OF SHAMBHALA ARCHIVES.

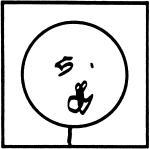

Pacifying.

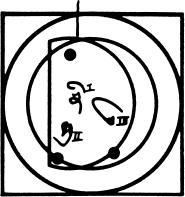

The circle within the square is connected with the first karma, pacifying. It represents the cooling off of neurosis. Traditionally, to relate to the principle of cooling off, we have to enter from the east, which in this case is down. [See line at bottom of circle. In Tibetan mandalas, east is below, west is on top, north is to the right, and south is to the left.] Entering from the east, we develop a sense of peace and coolness. In the middle, slightly off-center, is a cool situation, which cools off the boredom and heat of neurosis. [

Vidyadhara draws symbols in blue.

] It is pure, blue, cool. So the original manifestation, that of pacifying, is gentleness and freedom from neurosis. It is pure and cool.

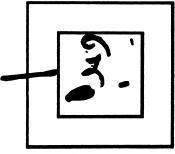

Enriching.

Within the same square shape, the same kind of wall, representing manifestation, we also can place the enriching principle, which is basically the absence of arrogance and aggression. We usually enter this mandala from the south. [See line at left.] Entering from the south, we begin to make a connection with richness. We no longer regard the square as a wall, but rather as our conquest of any areas where there might be arrogance. Arrogance is overcome, it is transparent. To make it clearer, I’ll put a little red into the paint; plain yellow seems rather weak, although yellow does make sense in representing the absence of arrogance.

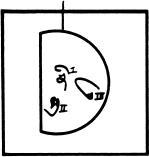

Magnetizing.

The basic principle of magnetizing is overcoming poverty. We approach it from the west. [See line at top of diagram.] Maybe this is too mysterious, but here are heaven, earth, and man. [

Vidyadhara draws symbols in red on diagram.

] It is free from poverty. It is very hard to say

why

all these things work, but it makes sense when you look at them properly, when you have some sense of visual perspective. So, ladies and gentlemen, it is up to you, and it is very traditional.

[

Vidyadhara draws symbols in green.

] In the manifestation of the fourth karma, destruction, we enter this particular energy field from the north. [See line at the right.] The background may be slightly problematic because it is supposed to come down a little further, but it gives you some idea of the principle of this karma, which is the destruction of laziness.

If we put all of the second series of diagrams together, we begin to have some idea of the whole thing. East represents awake; south represents expansion; west represents passion or magnetizing; north represents action. That seems to be the basic mandala principle that has developed.

Destroying.

Mandala 1.

[

Vidyadhara overlays original dot and circle over the four.

] On top of that we could add two lines that represent the psychological state of being; that is how far we could get into it. We are working toward the center and then, having become a practitioner, we go through the whole thing. [

Vidyadhara draws line completely across diagram.

] That is the basic visual diagram of the whole path, starting from hinayana, through mahayana, into vajrayana.

First of all, students enter from the east because they want to be relieved of their pain, they want to be peaceful. They enter from the south because they would also like to have some sense of richness in them, having already entered the path. They enter from the west because they would like to make a relationship with their community members, the sangha. They enter from the north because they would also like to activate or motivate working with the sangha. So apart from the artistic arrangement, there is a sociological setup that goes with the mandala principle as well. We can actually operate from this basic mandala principle—in flower arranging, horseback riding, dishwashing, and all the rest.

This final diagram is everything put together. It looks rather confusing in the middle, but it makes sense because we have the principles, and [displaying original dot and circle] we have the psychological state of being—why we want to become sane at all. It might look very confusing, but it might make sense. The entire Tibetan vajrayana iconography is based on this particular mandala principle. It works and did work and will work. It is quite obvious that it is possible to work with it.

Mandala 2.

There is always room to find your spot [the heaven principle]. And then from that particular spot you can branch out, which is the earth and man principle. Don’t panic. We can do it that way.

This discussion is not as abstract as you might think; it is more visual. It is worthwhile looking into these diagrams and colors as you study the basic principles. You might find these diagrams confusing, but if you look at them and develop your own diagrams and play with them, you might find that there is a reference point, and that the whole thing makes sense.

5. D

ISCIPLINE

“The concept of synchronizing body and mind is a total one, related to whatever work of art you execute or whatever life you lead.”

As you know already, the notion of space and its relationship to the artist’s point of view is very important. The temperature of that space, the coolness and absence of the heat of neurosis, also is very important as the background to our discussion. With that foundation, we also have the possibility of no longer freelancing, but educating ourselves through discipline, which is one of the foremost factors in the growing-up process. It all becomes a further learning situation: working with our world, our life, and our livelihood, as well as our art. Art is regarded as a way of life altogether, not necessarily as a trade or business.

We already talked about having a correct understanding of the work of art and not polluting the whole world by our artwork. We are trying to work to create a decent society where the work of art is respected and regarded as very sacred and does not become completely mercenary. On the other hand, certain artists have wanted to expand their vision and relate with as many people as possible. Quite possibly they did have a genuine reference point, and hundreds of thousands of people came along and appreciated their works of art. The question of how much restraint we should use and how much we should expand our vision and our energy to reach others is a very tricky one.

We are going to go back and reiterate the concept of heaven, earth, and man once more, in connection with what we have discussed already. The heaven, earth, and man principle that we are going to discuss will be accompanied by some on-the-spot calligraphies based on the principles of the four karmas: pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, and destroying.

In heaven, earth, and man, the first principle, as you know already, is heaven. It might be interesting for you to realize the psychological and physical implications of that principle in regard to executing a work of art. To begin with, the artist should have a feeling of connection with the brush or the musical instrument. Whatever medium you might use, you have a reference point to the body. This is connected with the idea of synchronizing body and mind. The concept of synchronizing body and mind is a total one, related to whatever work of art you execute or whatever life you lead. The way you dress yourself, the way you brush your hair, the way you brush your teeth, the way you take your shower or bath, the way you sit on your toilet—all of those basic activities are works of art in themselves. Art is life, rather than a gimmick. That is what we are talking about, not how the Buddhist concept can be salable and merchandised. I would like to remind you again and again, in case you forget, that art in this sense includes your total experience. And within that the mind and body are relating together.