The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Seven (42 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Seven Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

The suggestion that you practice sitting meditation before you execute a work of art is obviously a good one, but that does not mean that you have to become a Buddhist. It is simply that you can give yourself space, a gap where you can warm up and cool off all at once. That is ideal. If you do that, it will bring with it the notion of extending your mind by working through your sense perceptions. To extend our minds through our sense perceptions, we have to

use

our sense perceptions; in other words, use our bodies as vehicles. We could use the analogy of photography. We have a particular type of film, which represents the mind, and we put the film into a camera, which has different apertures and speeds, all of which represent the body. When the film and the camera—mind and body—coincide, then we at least have a good exposure: the film will react to light and we will have good, clear photography. But beyond that, there is also how we frame what we see, what kind of lens we use, and what composition we have in mind. The way we frame the picture is connected with the four karmas. It comes up once we have the settings and the film already in order.

Synchronizing body and mind is always the key. If we are artists, we have to live like artists. We have to treat our entire lives as our discipline. Otherwise we will be dilettante artists or, for that matter, schizophrenic artists. That has been a problem in the past, but hopefully we can correct that situation, so that artists live like the greatest practitioners, who see that there is no boundary between when they practice art and when they are not practicing art. The post-art and the actual art experience become one, just as postmeditation and meditation begin to become one. At that point the meditator or artist has greater scope to relate with his or her life completely and thoroughly. He or she has conquered the universe—overcome it somewhat. There is a tremendous cheerfulness and nothing to regret, no sharp edges to fight with. So things become good and soothing and very workable—with a tremendous smile.

Another way of looking at the heaven principle is as total discipline, which is free from hope and fear. The general experience is no hope, no fear, and it comes in that particular order: first no hope, then no fear. At first we might have no idea what we are going to execute as our work of art. Usually, in executing art, we would like to produce something, but we are left with our implements, our accoutrements, and we have no idea how we are going to proceed or which tool to begin with. So no hope comes first. No hope comes first because we are not trying to achieve anything other than our basic livelihood. After that comes no fear, because there is no sense of an ideal model we should achieve. Therefore, there is no fear. Very simply, we could say, “We have nothing to lose.”

When we have that attitude and motivation, we are victorious, because we are not afraid of falling into any dungeons, nor do we hope for any particular high point. There is a general sense of even-mindedness, which could also be called genuineness or decency.

Decency

is a very important word for artists because when we say, “

I’m

an artist,” there is always a tinge of doubt. Maybe we are not telling the truth, but we might be making something up. So the whole principle of decency is trying to live up to that particular truth. We might be hopeful and we might be fearful. For instance, in modern society, many people are afraid of truth. That is why we find so many law firms willing to protect a lie. We can employ lawyers to support our lies and twists on the truth. A lot of lawyers make a lot of money that way. So lawyers and artists could both be questionable.

Being without fear and without hope, which is the heaven principle, provides a lot of freedom, a lot of space. It is not freedom in the sense of blatantly coming out with all sorts of self-styled expressions of imprisonment. Some people regard that as an expression of freedom. If they can clearly express their imprisonment, they begin to feel that they have made some kind of breakthrough. That can go on and on and on. People tried that approach in the fifties and sixties quite a lot in America. But they came back to square one in the seventies. Without getting into too much politics, here the notion of freedom is a letting-go process. There is enough room to express yourself. That is the definition of freedom. There is room for you to demonstrate your free style—not that of imprisonment, but the possibility of freedom from imprisonment altogether.

The earth principle comes after that. Earth is usually regarded as very solid and stubborn, as something we think we can’t be friendly toward. Digging soil takes a lot of effort and energy. But here there is a twist of logic: the earth principle is unobstructed; there is no obstacle. But we should not misunderstand this, thinking that the earth is pliable, that there is no ground to stand on, or that the earth will change. It all depends on our trip—or trips. Earth is somewhat solid, but at the same time earth can be penetrated very easily, with no obstructions. This is a very important point. Because it is related with the heaven principle of no hope and no fear, that actually brings down raindrops onto the earth, so earth can be penetrated, worked on. Because of that, there are possibilities of cultivating the earth and growing vegetation in it, and using it as a resource for cows to graze on. The possibilities are infinite.

But something is missing from the logic of the relationship between heaven and earth. The heaven principle of no hope and no fear could become very dry and too logical. We need some kind of warmth coming from heaven as well. If you put no hope and no fear together, that mounts up almost mathematically into tremendous warmth and love. Therefore when we have heaven, we could have raindrops coming down, making a sympathetic connection with earth. When that connection takes place, things are not so cut and dried. The more that relationship comes down from heaven, the more the earth begins to yield. Therefore the earth becomes gentle and soft and pliable, and can actually produce greenery.

Then we have man, which is connected with both those principles: being without hope and without fear, and being unobstructed. Man can survive with the mercy of heaven and earth and have a good relationship with both of them. It is almost a traditional, scientific truth that when heaven and earth have a good relationship, man has a good relationship with them. When heaven and earth are fighting, there is drought and starvation. All kinds of problems come from the conflict between heaven and earth. Whenever there is that kind of conflict, men and women begin to have doubts about their king, who is supposed to have the power to join heaven and earth but is not quite able to do so, as in the Judeo-Christian story of King David. Whenever there is plenty of rain and plenty of greenery, men feel that their king is worthwhile.

The man principle is known as simplicity: freedom from concepts, freedom from trappings. Men could actually enjoy the freedom from hope and fear of heaven and the pliability of earth. Therefore they could live together and relate to one another. The idea of the sky falling on their heads is no longer a threat. They know that the sky will always be there and that the earth will always be there. There is no fear that the sky and earth are going to chew man up and eat him. A lot of the fear of natural disasters comes out of man’s distrust of heaven and earth and of the four seasons working harmoniously together. When there is no fear, man begins to join in, as he deserves, living in this world. He has heaven above and earth below and he begins to appreciate the trees and greenery, bananas, oranges, and what have you.

In connection with the heaven, earth, and man principle, we have a fourth category, that of the four karmas. We are free from acceptance and rejection when we begin to realize pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, and destroying as the natural expression of our desire to work with the whole universe. We are free from accepting too eagerly or rejecting too violently; we are free from push and pull. In Buddhism that freedom is known as the mandala principle, in which everything is moderated by those four activities. You can express heaven and earth as pacifying or enriching or magnetizing or destroying: all four karmas are connected with joining heaven and earth. Because we are free from acceptance and rejection there is a basic notion of how we can handle the whole world. So the idea of the four karmas is not so much how we can handle ourselves, particularly, but it is how we can relate with the radiation coming out of the heaven, earth, and man principle. For example, if you are sitting on a meditation cushion, you can see how large a radius you cover around yourself and your neighbors, and the relationships connected with that.

At this point we could execute a few calligraphies connected with the heaven, earth, and man principle and with the four karmas. The brush I am using tonight is not trained yet—it’s been waiting here a long time in this hot climate, and it hasn’t been soaked in water yet. But we’ll see what we can do. [

Vidyadhara begins to execute calligraphies.

]

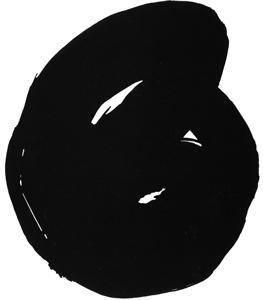

First, we go through the process of pacifying, in connection with the heaven, earth, and man principle.

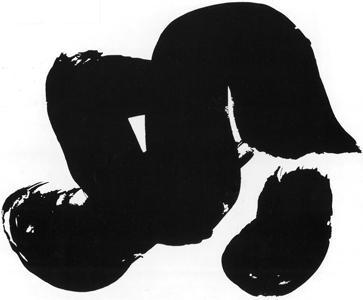

With enriching we begin from the south. It takes time to do the calligraphy in the form of a rabbit’s jump.

Magnetizing is very delicate and very difficult, quite difficult. I wonder if I should do it at all. It begins from the west. The sense of seduction lies in the rhythm; at the same time it is genuine seduction.

Now destruction. It’s very simple. We take our brush stroke from the north, the direction of the karma family. It is clean cut, as if you were running into Wilkinson’s sword—or for that matter, Kiku Masamune (a brand of sake). It cuts in all directions. Very simple.