The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Seven (39 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Seven Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

The notion of looking at things as they are is a very important concept. We cannot even call it a concept, it is an experience. Look! Why do we look at all? Or we could say, Listen! Why do we listen at all? Why do we feel at all? Why do we taste? The one and only answer is that there is such a thing as inquisitiveness in our makeup. Inquisitiveness is the seed syllable of the artist. The artist is interested in sight, sound, feelings, and touchable objects. We are interested and we are inquisitive, very inquisitive, and we are willing to explore in any way we can. We appreciate purple, blue, red, white, yellow, violet. When we see them, we are so interested. Nobody knows why, but purple looks good and sounds good, and red sounds and looks good. And we discover the different shades of each color as well. We appreciate colors as we hear them, as we feel them. Such tremendous inquisitiveness is the key point in the way we look at things, because with inquisitiveness we have a connection.

We as human beings each have a particular kind of body. We have certain sense organs, such as eyes, noses, ears, mouths, and tongues, to experience the different levels of sense perceptions. And our minds, basically speaking, can communicate thoroughly and properly through any one of those sense organs. But there is a problem of synchronizing body and mind only within the particular area connected with a person’s work of art. For example, a person could be a fantastic painter but a bad writer, or a good musician but a bad sculptor. We should not say that we are being punished or that we have no possibilities of correcting or improving that situation. Instead, by training ourselves in the practice of meditation and by training ourselves in the understanding of art as a fundamental and basic discipline, we could learn to synchronize our mind and body completely. Then, ideally speaking, we could accomplish any artistic discipline. Our mind and body have hundreds of thousands of shortcomings, but they are not regarded as punishment or as original sin. Instead they can be corrected and our mind and body synchronized properly. In doing so the first step is learning how to look, how to listen, how to feel. By learning how to look, we begin to discover how to see; by learning how to listen, we learn how to hear; by learning how to feel, we learn how to experience.

To begin with, we need to understand the general projection of the first perception, when you first look. The reason you are compelled to look is because of your inquisitiveness, and because of your inquisitiveness, you begin to see things. Usually, in nontheistic discipline, you look first and then you see things. Looking is prajna, intellect; seeing is wisdom [jnana]. After that you find your heaven principle. Heaven is the definite discovery of the product of what you are looking for, what you are seeing. This analysis is very scientific; it has been described in the abhidharma teachings of Buddhist philosophy. When sense objects and sense perceptions and sense organs meet, and they begin to be synchronized, you let yourself go a little further; you open yourself. It is like a camera aperture: your lens is open at that point. Then you see things, and they reflect into your state of mind. After that, you make a decision that what you’ve seen is either desirable or undesirable—and you make further decisions after that. That seems to be the basic idea of how a perceiver looks at a work of art.

The heaven, earth, and man principle could be applied to this process of perception. Having looked, you see the big thing first. This does not mean that you see a monolithic object or hear a monolithic sound: you may see a little flea or a gigantic mountain—from this perspective, they are the same. It is simply the first perception of

that,

which sets the foundation. That is the heaven principle. In discussing the creation of art, first thought is the second principle, or earth. But from the viewpoint of the perceiver of art, first thought is heaven. That big thing, that initial perception, breaks through your subconscious gossip. Sometimes it is shocking, sometimes it is pleasant, but whatever the case, a big thing happens—

that

—which is heaven. In the ikebana tradition, heaven is the first branch you place in your kenzan, the principal branch. It may be a breakthrough, maybe not quite.

After that, you have earth, which is a confirmation of that big thing. Earth allows the heaven principle to be legitimate, in the sense that it is your initial perception which allows you to do that second thing. As this second action is in accordance with your first perception, therefore your initial perception becomes legitimate and complementary.

Having organized heaven and earth together, you feel at ease and comfortable. So you add the man principle as the third situation, which makes you feel, “Whew! Wow, I’ve done it!” You could generate little messages or little bits of playful information, which makes the whole situation simple and straight—and also jazzes it up, decorates it. All these little touches are expressions of inquisitiveness, as well as expressions that because you looked, because you listened, therefore you saw, therefore you heard.

We are trying to work with that general principle of heaven, earth, and man. It takes a long time to learn not to jump the gun. Usually we are very impatient. We have a tremendous tendency to look for a quick discovery or for proof that what we have done is good, that we have discovered something, that we have made it, that it worked, that it is marketable, and so forth. But none of those impatient approaches show any understanding of looking and seeing at all.

The general approach of heaven, earth, and man is that things have to be done on a grand scale, whether you like it or not, with tremendous preparation. Ideally, you have to experience the basic ground in which situations are clean, workable, and pliable, in which all the implements are there. You do not try to cover up when an emergency occurs: you do not run to the closest supermarket to purchase Band-Aids or Scotch Tape or aspirin.

For the general work or discipline of art, both as students perceive it and as artists conduct themselves in its creation, there needs to be a good environment. The preparation of the environment is very important. In order to ride your horse, you have to have a good saddle as well as a good horse, if you can afford to buy one. In order to paint on canvas, you have to have a good brush and good paints and a good studio. Trying to ignore this inconvenience, working in your mouse hole or in your basement, might have worked for people in medieval times, but in the twentieth century it doesn’t. If you take that approach, you might be regarded as a veteran because you were willing to survive the dirt in order to present your glorious art, but unfortunately, very few artists who live like that come up with good results. Instead, many of them develop tremendous negativity and resentment toward society. Their resentment starts with their landlords, because they have had to work on their fantastic works of art in cold, damp basements for so many hours. Then they complain to their friends, who have never acknowledged or experienced what they have gone through. Then they begin to develop further complaints toward their world in general and toward their teacher. They begin to build up all sorts of garbage and negativity that way.

Some room for self-respect in a work of art is absolutely necessary. Furthermore, the implements we use in creating a work of art are regarded as sacred. If we were completely oppressed, if we had been persecuted to the extent that we could not even show our work of art, we might have to do it in a dungeon—but we are not facing that yet. We can afford to rise and take pleasure in what we are doing. We can have respect for what we are doing and appreciate the sacredness of the whole thing.

In discussing the principle of heaven, earth, and man, we are working on how the structure of perception relates with one’s sense fields, so to speak. We are talking in terms of a basic state of mind in which we have already developed a notion of ourselves and our communication with others. When others are working with us and we are working with them, there is a general sense of play back and forth and also some sense of basic existence. Where do such situations come from? They come from our practice of meditation. We no longer regard a work of art as a gimmick or as confirmation, it is simply expression—not even self-expression, just expression. We could safely say that there is such a thing as unconditional expression that does not come from self or other. It manifests out of nowhere like mushrooms in a meadow, like hailstones, like thundershowers.

The basic sense of delight and spontaneity in a person who has opened fully and thoroughly to himself and life can provide wonderful rainbows and thundershowers and gusts of wind. We don’t have to be tied down to the greasy-spoon world of well-meaning artists with their heavy-handed looks on their faces and overfed information in their brains. The basic idea of dharma art is the sense of peace and the refreshing coolness of the absence of neurosis. If there is no refreshing coolness, you are unable even to lift up your brush to paint on your canvas. You find that your brush weighs ten thousand tons. You are weighted down by your depression and laziness and neurosis. On the other hand, you cannot take what’s known as “poetic license,” doing everything freestyle. That would be like hoping that the rock you throw at night will land on your enemy’s head.

4. T

HE

M

ANDALA OF THE

F

OUR

K

ARMAS

“The entire Tibetan vajrayana iconography is based on this particular mandala principle. It works and did work and will work.”

The principle of heaven, earth, and man could be illustrated by means of a series of diagrams.

The heaven, earth, and man arrangement can exist on the basis of two situations. The first is that the innate nature of heaven, earth, and man exists in us as basic talent. This innate nature that we are going to work on is connected with a particular shape, the circle. The basic, innate nature of our existence and sense of perception is the circle.

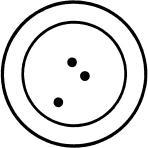

Diagram 1.

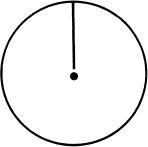

Then there is the sense of first dot, which is expanded with a line coming from that dot. First dot is best dot! The basic idea here is that the blank space is heaven and the first dot is earth. On the other hand, we could also talk about the whole thing, the first dot surrounded by a circle, as being the heaven principle.

Pacifying 1.

Within that first dot concept, we have a basic circle, as you can see. The circle is the idea of the basic innate nature of the heaven, earth, and man principle. The outer circle represents mind, and the inner circle represents energy. So the perimeter is thought, and the inner circle is a particular type of energy.

According to the vajrayana tradition, four basic types of energies exist, called the four karmas, or actions. The round shape of the inner circle represents gentleness and innate goodness. This is the first karma, which is the principle of peace, or pacifying. Innate goodness possesses gentleness and is absent of neurosis. These things could be experienced.