The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 (14 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

Q:

Can there be awareness without a watcher?

A:

Yes, because the watcher is only paranoia. You could have complete openness, a panoramic situation, without having to discriminate between two parties, “I” and “other.”

Q:

Would that awareness involve feelings of bliss?

A:

I do not think so, because bliss is a very individual experience. You are separate and you are experiencing your bliss. When the watcher is gone, there is no evaluation of the experience as being pleasant or painful. When you have panoramic awareness without the evaluation of the watcher, then the bliss becomes irrelevant, by the very fact that there is no one experiencing it.

The Hard Way

I

NASMUCH AS NO ONE

is going to save us, to the extent that no one is going magically to enlighten us, the path we are discussing is called the “hard way.” This path does not conform to our expectation that involvement with the Buddhist teaching will be gentle, peaceful, pleasant, compassionate. It is the hard way, a simple meeting of two minds: if you open your mind, if you are willing to meet, then the teacher opens his mind as well. It is not a question of magic; the condition of openness is a mutual creation.

Generally, when we speak of freedom or liberation or spiritual understanding, we think that to attain these things we need do nothing at all, that someone else will take care of us. “You are all right, don’t worry, don’t cry, you’re going to be all right. I’ll take care of you.” We tend to think that all we have to do is make a commitment to the organization, pay our initiation fee, sign the register, and then follow the instructions given us. “I am firmly convinced that your organization is valid, it answers all my questions. You may program me in any way. If you want to put me into difficult situations, do so. I leave everything to you.” This attitude supplies the comfort of having to do nothing but follow orders. Everything is left to the other person, to instruct you and relieve you of your shortcomings. But to our surprise things do not work that way. The idea that we do not have to do anything on our own is extremely wishful thinking.

It takes tremendous effort to work one’s way through the difficulties of the path and actually get into the situations of life thoroughly and properly. So the whole point of the hard way seems to be that some individual effort must be made by the student to acknowledge himself, to go through the process of unmasking. One must be willing to stand alone, which is difficult.

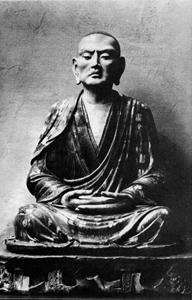

Lohan.

An arhat in meditation posture, a disciple of the Buddha.

WILLIAM ROCKHILL NELSON GALLERY OF ART, KANSAS CITY, MO.

This is not to say that the point of the hard way is that we must be heroic. The attitude of “heroism” is based upon the assumption that we are bad, impure, that we are not worthy, are not ready for spiritual understanding. We must reform ourselves, be different from what we are. For instance, if we are middle-class Americans, we must give up our jobs or drop out of college, move out of our suburban homes, let our hair grow, perhaps try drugs. If we are hippies, we must give up drugs, cut our hair short, throw away our torn jeans. We think that we are special, heroic, that we are turning away from temptation. We become vegetarians and we become this and that. There are so many things to become. We think our path is spiritual because it is literally against the flow of what we used to be, but it is merely the way of false heroism, and the only one who is heroic in this way is ego.

We can carry this sort of false heroism to great extremes, getting ourselves into completely austere situations. If the teaching with which we are engaged recommends standing on our heads for twenty-four hours a day, we do it. We purify ourselves, perform austerities, and we feel extremely cleansed, reformed, virtuous. Perhaps there seems to be nothing wrong with it at the time.

We might attempt to imitate certain spiritual paths, such as the American Indian path or the Hindu path or the Japanese Zen Buddhist path. We might abandon our suits and collars and ties, our belts and trousers and shoes in an attempt to follow their example. Or we may decide to go to northern India in order to join the Tibetans. We might wear Tibetan clothing and adopt Tibetan customs. This will seem to be the “hard way,” because there will always be obstacles and temptations to distract us from our purpose.

Sitting in a Hindu ashram, we have not eaten chocolate for six or seven months, so we dream of chocolate, or other dishes that we like. Perhaps we are nostalgic on Christmas or New Year’s Day. But still we think we have found the path of discipline. We have struggled through the difficulties of this path and have become quite competent, masters of discipline of some sort. We expect the magic and wisdom of our training and practice to bring us into the right state of mind. Sometimes we think we have achieved our goal. Perhaps we are completely “high” or absorbed for a period of six or seven months. Later our ecstasy disappears. And so it goes, on and on, on and off. How are we going to deal with this situation? We may be able to stay “high” or blissful for a very long time, but then we have to come back or come down or return to normal.

I am not saying that foreign or disciplinary traditions are not applicable to the spiritual path. Rather, I am saying that we have the notion that there must be some kind of medicine or magic potion to help us attain the right state of mind. This seems to be coming at the problem backward. We hope that by manipulating matter, the physical world, we can achieve wisdom and understanding. We may even expect expert scientists to do it for us. They might put us into a hospital, administer the correct drugs, and lift us into a high state of consciousness. But I think, unfortunately, that this is impossible, we cannot escape what we are, we carry it with us all the time.

So the point we come back to is that some kind of

real

gift or sacrifice is needed if we are to open ourselves completely. This gift may take any form. But in order for it to be meaningful, it must entail giving up our hope of getting something in return. It does not matter how many titles we have, nor how many suits of exotic clothes we have worn through, nor how many philosophies, commitments and sacramental ceremonies we have participated in. We must give up our ambition to get something in return for our gift. That is the really hard way.

We may have had a wonderful time touring around Japan. We may have enjoyed Japanese culture, beautiful Zen temples, magnificent works of art. And not only did we find these experiences beautiful, but they said something to us as well. This culture is the creation of a whole lifestyle completely different from that of the Western world, and these creations spoke to us. But to what extent does the exquisiteness of culture and images, the beauty of the external forms really shake us, deal with us? We do not know. We merely want to savor our beautiful memories. We do not want to question our experiences too closely. It is a sensitive area.

Or perhaps a certain guru has initiated us in a very moving, extremely meaningful ceremony. That ceremony was real and direct and beautiful, but how much of the experience are we willing to question? It is private, too sensitive to question. We would rather hoard and preserve the flavor and beauty of the experience so that, when bad times come, when we are depressed and down, we can bring that memory to mind in order to comfort ourselves, to tell ourselves that we have actually done something worthwhile, that, yes, we are on the path. This does not seem to be the hard way at all.

On the contrary, it would seem that we have been collecting rather than giving. If we reconsider our spiritual shopping, can we remember an occasion when we gave something completely and properly, opened ourselves and gave everything? Have we ever unmasked, stripping out of our suit of armor and our shirt and skin and flesh and veins, right down to the heart? Have we really experienced the process of stripping and opening and giving? That is the fundamental question. We must really surrender, give something, give something up in a very painful way. We must begin to dismantle the basic structure of this ego we have managed to create. The process of dismantling, undoing, opening, giving up, is the real learning process. How much of this ingrown toenail situation have we decided to give up? Most likely, we have not managed to give up anything at all. We have only collected, built, adding layer upon layer. So the prospect of the hard way is very threatening.

The problem is that we tend to seek an easy and painless answer. But this kind of solution does not apply to the spiritual path, which many of us should not have begun at all. Once we commit ourselves to the spiritual path, it is very painful and we are in for it. We have committed ourselves to the pain of exposing ourselves, of taking off our clothes, our skin, nerves, heart, brains, until we are exposed to the universe. Nothing will be left. It will be terrible, excruciating, but that is the way it is.

Somehow we find ourselves in the company of a strange doctor. He is going to operate on us, but he is not going to use an anesthetic because he really wants to communicate with our illness. He is not going to allow us to put on our facade of spirituality, psychological sophistication, false psychological illness, or any other disguise. We wish we had never met him. We wish we understood how to anesthetize ourselves. But now we are in for it. There is no way out. Not because he is so powerful. We could tell him goodbye in a minute and leave. But we have exposed so much to this physician and, if we have to do it all over again, it will be very painful. We do not want to have to do it again. So now we have to go all the way.

Being with this doctor is extremely uncomfortable for us because we are continually trying to con him, although we know that he sees through our games. This operation is his only way to communicate with us, so we must accept it; we must open ourselves to the hard way, to this operation. The more we ask questions—“What are you going to do to me?”—the more embarrassed we become, because we know what we are. It is an extremely narrow path with no escape, a painful path. We must surrender ourselves completely and communicate with this physician. Moreover, we must unmask our expectations of magic on the part of the guru, that with his magical powers he can initiate us in certain extraordinary and painless ways. We have to give up looking for a painless operation, give up hope that he will use an anesthetic or sedative so that when we wake up everything will be perfect. We must be willing to communicate in a completely open and direct way with our spiritual friend and with our life, without any hidden corners. It is difficult and painful, the hard way.

Q:

Is exposing yourself something that just happens, or is there a way of doing it, a way of opening?

A:

I think that if you are already committed to the process of exposing yourself, then the less you try to open the more the process of opening becomes obvious. I would say it is an automatic action rather than something that you have to do. At the beginning when we discussed surrendering, I said that once you have exposed everything to your spiritual friend, then you do not have to do anything at all. It is a matter of just accepting what is, which we tend to do in any case. We often find ourselves in situations completely naked, wishing we had clothes to cover ourselves. These embarrassing situation always come to us in life.

Q:

Must we have a spiritual friend before we can expose ourselves, or can we just open ourselves to the situations of life?

A:

I think you need someone to watch you do it, because then it will seem more real to you. It is easy to undress in a room with no one else around, but we find it difficult to undress ourselves in a room full of people.

Q:

So it is really exposing ourselves to ourselves?

A:

Yes. But we do not see it that way. We have a strong consciousness of the audience because we have so much awareness of ourselves.

Q:

I do not see why performing austerities and mastering discipline is not the “real” hard way.

A:

You can deceive yourself, thinking you are going through the hard way, when actually you are not. It is like being in a heroic play. The “soft way” is very much involved with the experience of heroism, while the hard way is much more personal. Having gone through the way of heroism, you still have the hard way to go through, which is a very shocking thing to discover.

Q:

Is it necessary to go through the heroic way first and is it necessary to persevere in the heroic way in order to continue on the truly hard way?

A:

I don’t think so. This is what I am trying to point out. If you involve yourself with the heroic way, you add layers or skins to your personality because you think you have achieved something. Later, to your surprise, you discover that something else is needed. One must

remove

the layers, the skins.