The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 (29 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

To the conventional way of thinking, compassion simply means being kind and warm. This sort of compassion is described in the scriptures as “grandmother’s love.” You would expect the practitioner of this type of compassion to be extremely kind and gentle; he would not harm a flea. If you need another mask, another blanket to warm yourself, he will provide it. But true compassion is ruthless, from ego’s point of view, because it does not consider ego’s drive to maintain itself. It is “crazy wisdom.” It is totally wise, but it is crazy as well, because it does not relate to ego’s literal and simple-minded attempts to secure its own comfort.

The logical voice of ego advises us to be kind to other people, to be good boys and girls and lead innocent little lives. We work at our regular jobs and rent a cozy room or apartment for ourselves; we would like to continue in this way, but suddenly something happens which tears us out of our secure little nest. Either we become extremely depressed or something outrageously painful occurs. We begin to wonder why heaven has been so unkind. “Why should God punish me? I have been a good person, I have never hurt a soul.” But there is something more to life than that.

What are we trying to secure? Why are we so concerned to protect ourselves? The sudden energy of ruthless compassion severs us from our comforts and securities. If we were never to experience this kind of shock, we would not be able to grow. We have to be jarred out of our regular, repetitive, and comfortable lifestyles. The point of meditation is not merely to be an honest or good person in the conventional sense, trying only to maintain our security. We must begin to become compassionate and wise in the fundamental sense, open and relating to the world as it is.

Q:

Could you discuss the basic difference between love and compassion and in what relation they stand to each other?

A:

Love and compassion are vague terms; we can interpret them in different ways. Generally in our lives we take a grasping approach, trying to attach ourselves to different situations in order to achieve security. Perhaps we regard someone as our baby, or, on the other hand, we might like to regard ourselves as helpless infants and leap into someone’s lap. This lap might belong to an individual, an organization, a community, a teacher, any parental figure. So-called “love” relationships usually take one of these two patterns. Either we are being fed by someone or we are feeding others. These are false, distorted kinds of love or compassion. The urge to commitment—that we would like to “belong,” be someone’s child, or that we would like them to be our child—is seemingly powerful. An individual or organization or institution or anything could become our infant; we would nurse it, feed it milk, encourage its growth. Or else the organization is the great mother by which we are continuously fed. Without our “mother” we cannot exist, cannot survive. These two patterns apply to any life energy which has the potential to entertain us. This energy might be as simple as a casual friendship or an exciting activity we would like to undertake, and it might be as complicated as marriage or our choice of career. Either we would like to control the excitement or we would like to become a part of it.

However, there is another kind of love and compassion, a third way. Just be what you are. You do not reduce yourself to the level of an infant nor do you demand that another person leap into your lap. You simply be what you are in the world, in life. If you can be what you are, external situations will become as they are, automatically. Then you can communicate directly and accurately, not indulging in any kind of nonsense, any kind of emotional or philosophical or psychological interpretation. This third way is a balanced way of openness and communication which automatically allows tremendous space, room for creative development, space in which to dance and exchange.

Compassion means that we do not play the game of hypocrisy or self-deception. For instance, if we want something from someone and we say, “I love you,” often we are hoping that we will be able to lure them into our territory, over to our side. This kind of proselytizing love is extremely limited. “You should love me, even if you hate me, because I am filled with love, am high on love, am completely intoxicated!” What does it mean? Simply that the other person should march into your territory because you say that you love him, that you are not going to harm him. It is very fishy. Any intelligent person is not going to be seduced by such a ploy. “If you really love me as I am, why do you want me to enter your territory? Why this issue of territory and demands at all? What do you want from me? How do I know, if I do march into your ‘loving’ territory, that you aren’t going to dominate me, that you won’t create a claustrophobic situation with your heavy demands for love?” As long as there is territory involved with a person’s love, other people will be suspicious of his “loving” and “compassionate” attitude. How do we make sure, if a feast is prepared for us, that the food is not dosed with poison? Does this openness come from a centralized person, or is it total openness?

The fundamental characteristic of true compassion is pure and fearless openness without territorial limitations. There is no need to be loving and kind to one’s neighbors, no need to speak pleasantly to people and put on a pretty smile. This little game does not apply. In fact it is embarrassing. Real openness exists on a much larger scale, a revolutionarily large and open scale, a universal scale. Compassion means for you to be as adult as you are, while still maintaining a childlike quality. In the Buddhist teachings they symbol for compassion, as I have already said, is one moon shining in the sky while its image is reflected in one hundred bowls of water. The moon does not demand, “If you open to me, I will do you a favor and shine on you.” The moon just shines. The point is not to want to benefit anyone or make them happy. There is no audience involved, no “me” and “them.” It is a matter of an open gift, complete generosity without the relative notions of giving and receiving. That is the basic openness of compassion: opening without demand. Simply be what you are, be the master of the situation. If you will just “be,” then life flows around and through you. This will lead you into working and communicating with someone, which of course demands tremendous warmth and openness. If you can afford to be what you are, then you do not need the “insurance policy” of trying to be a good person, a pious person, a compassionate person.

Q:

This ruthless compassion sounds cruel.

A:

The conventional approach to love is like that of a father who is extremely naive and would like to help his children satisfy all their desires. He might give them everything: money, drink, weapons, food, anything to make them happy. However, there might be another kind of father who would not merely try to make his children happy, but who would work for their fundamental health.

Q:

Why would a truly compassionate person have any concern with giving anything?

A:

It is not exactly giving but opening, relating to other people. It is a matter of acknowledging the existence of other people as they are, rather than relating to people in terms of a fixed and preconceived idea of comfort or discomfort.

Q:

Isn’t there a considerable danger of self-deception involved with the idea of ruthless compassion? A person might think he is being ruthlessly compassionate, when in fact he is only releasing his aggressions.

A:

Definitely, yes. It is because it is such a dangerous idea that I have waited until now to present it, after we have discussed spiritual materialism and the Buddhist path in general and have laid a foundation of intellectual understanding. At the stage of which I am speaking, if a student is to actually practice ruthless compassion, he must have already gone through a tremendous amount of work: meditation, study, cutting through, discovering self-deception and sense of humor, and so on. After a person has experienced this process, made this long and difficult journey, then the next discovery is that of compassion and prajna. Until a person has studied and meditated a great deal, it would be extremely dangerous for him to try to practice ruthless compassion.

Q:

Perhaps a person can grow into a certain kind of openness, compassion with regard to other people. But then he finds that even this compassion is still limited, still a pattern. Do we always rely on our openness to carry us through? Is there any way to make sure we are not fooling ourselves?

A:

That is very simple. If we fool ourselves at the beginning, there will be some kind of agreement that we automatically make with ourselves. Surely everyone has experienced this. For instance, if we are speaking to someone and exaggerating our story, before we even open our mouths we will say to ourselves, “I know I am exaggerating, but I would like to convince this person.” We play this little game all the time. So it is a question of really getting down to the nitty-gritty of being honest and fully open with ourselves. Openness to other people is not the issue. The more we open to ourselves, completely and fully, then that much more openness radiates to others. We really know when we are fooling ourselves, but we try to play deaf and dumb to our own self-deception.

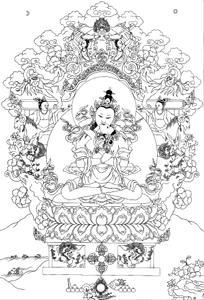

Vajradhara and consort. The personification of Shakyamuni Buddha teaching tantra. Symbol of the Absolute in its polarity aspect.

DRAWING BY GLEN EDDY.

Tantra

A

FTER THE BODHISATTVA

has cut through fixed concepts with the sword of prajna, he comes to the understanding that “form is form, emptiness is emptiness.” At this point he is able to deal with situations with tremendous clarity and skill. As he journeys still further along the bodhisattva path, prajna and compassion deepen and he experiences greater awareness of intelligence and space and greater awareness of peace. Peace in this sense is indestructible, tremendously powerful. We cannot be truly peaceful unless we have the invincible quality of peace within us; a feeble or temporary peacefulness could always be disturbed. If we try to be kind and peaceful in a naive way, encountering a different or unexpected situation might interfere with our awareness of peace because that peace has no strength in it, has no character. So peace must be stable, deep-rooted, and solid. It must have the quality of earth. If we have power in ego’s sense, we tend to exert that power and use it as our tool to undermine others. But as bodhisattvas we do not use power to undermine people; we simply remain peaceful.

Finally we reach the tenth and last stage of the bodhisattva path: the death of shunyata and the birth into “luminosity.” Shunyata as an experience falls away, exposing the luminous quality of form. Prajna transforms into jnana or “wisdom.” But wisdom is still experienced as an external discovery. The powerful jolt of the vajra-like samadhi is necessary to bring the bodhisattva into the state of

being

wisdom rather than

knowing

wisdom. This is the moment of bodhi or “awake,” the entrance into tantra. In the awakened state the colorful, luminous qualities of the energies become still more vivid.

If we see a red flower, we not only see it in the absence of ego’s complexity, in the absence of preconceived names and forms, but we also see the brilliance of that flower. If the filter of confusion between us and the flower is suddenly removed, automatically the air becomes quite clear and vision is very precise and vivid.

While the basic teaching of mahayana buddhism is concerned with developing prajna, transcendental knowledge, the basic teaching of tantra is connected with working with energy. Energy is described in the

Kriyayoga Tantra

of Vajramala as “that which abides in the heart of all beings, self-existing simplicity, that which sustains wisdom. This indestructible essence is the energy of great joy; it is all-pervasive, like space. This is the dharma body of nondwelling.” According to this tantra, “This energy is the sustainer of the primordial intelligence which perceives the phenomenal world. This energy gives impetus to both the enlightened and the confused states of mind. It is indestructible in the sense of being constantly ongoing. It is the driving force of emotion and thought in the confused state, and of compassion and wisdom in the enlightened state.”

In order to work with this energy the yogi must begin with the surrendering process and then work on the shunyata principle of seeing beyond conceptualization. He must penetrate through confusion, seeing that “form is form and emptiness is empty,” until finally he even cuts through dwelling upon the shunyata experience and begins to see the luminosity of form, the vivid, precise, colorful aspect of things. At this point whatever is experienced in everyday life through sense perception is a naked experience, because it is direct. There is no veil between him and “that.” If a yogi works with energy without having gone through the shunyata experience, then it may be dangerous and destructive. For example, the practice of some physical yoga exercises which stimulate one’s energy could awaken the energies of passion, hatred, pride, and other emotions to the extent that one would not know how to express them. The scriptures describe a yogi who is completely intoxicated with his energy as being like a drunken elephant who runs rampant without considering where he is going.