The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 (43 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

The fourth aspect of the eightfold path is “right morality” or “right discipline.” If there is no one to impose discipline and no one to impose discipline on, then there is no need for discipline in the ordinary sense at all. This leads to the understanding of right discipline, complete discipline, which does not exist relative to ego. Ordinary discipline exists only at the level of relative decisions. If there is a tree, there must be branches; however, if there is no tree, there are no such things as branches. Likewise, if there is no ego, a whole range of projections becomes unnecessary. Right discipline is that kind of giving-up process; it brings us into complete simplicity.

We are all familiar with the samsaric kind of discipline which is aimed at self-improvement. We give up all kinds of things in order to make ourselves “better,” which provides us with tremendous reassurance that we can

do

something with our lives. Such forms of discipline are just unnecessarily complicating your life rather than trying to simplify and live the life of a rishi.

Rishi

is a Sanskrit word which refers to the person who constantly leads a straightforward life. The Tibetan word for “rishi” is

trangsong (drang sron). Trang

means “direct,”

song

means “upright.” The term refers to one who leads a direct and upright life by not introducing new complications into his life situation. This is a permanent discipline, the ultimate discipline. We simplify life rather than get involved with new gadgets or finding new concoctions with which to mix it.

The fifth point is “right livelihood.” According to Buddha, right livelihood simply means making money by working, earning dollars, pounds, francs, pesos. To buy food and pay rent you need money. This is not a cruel imposition on us. It is a natural situation. We need not be embarrassed by dealing with money nor resent having to work. The more energy you put out, the more you get in. Earning money involves you in so many related situations that it permeates your whole life. Avoiding work usually is related to avoiding other aspects of life as well.

People who reject the materialism of American society and set themselves apart from it are unwilling to face themselves. They would like to comfort themselves with the notion that they are leading philosophically virtuous lives, rather than realizing that they are unwilling to work with the world as it is. We cannot expect to be helped by divine beings. If we adopt doctrines which lead us to expect blessings, then we will not be open to the real possibilities in situations. Buddha believed in cause and effect. For example, you get angry at your friend and decide to cut off the relationship. You have a hot argument with him and walk out of the room and slam the door. You catch your finger in the door. Painful, isn’t it? That is cause and effect. You realize there is some warning there. You have overlooked karmic necessity. It happens all the time. This is what we run into when we violate right livelihood.

The sixth point is “right effort.” The Sanskrit,

samyagvyayama,

means energy, endurance, exertion. This is the same as the bodhisattva’s principle of energy. There is no need to be continually just pushing along, drudging along. If you are awake and open in living situations, it is possible for them and you to be creative, beautiful, humorous, and delightful. This natural openness is right effort, as opposed to any old effort. Right effort is seeing a situation precisely as it is at that very moment, being present fully, with delight, with a grin. There are occasions when we know we are present, but we do not really want to commit ourselves, but right effort involves full participation.

For right effort to take place we need gaps in our discursive or visionary gossip, room to stop and be present. Usually, someone is whispering some kind of seduction, some gossip behind our back; “It’s all very well to meditate, but how about going to the movies? Meditating is nice, but how about getting together with our friends? How about that? Shall we read that book? Maybe we should go to sleep. Shall we go buy that thing we want? Shall we? Shall we? Shall we?” Discursive thoughts constantly happening, numerous suggestions constantly being supplied—effort has no room to take place. Or maybe it is not discursive thoughts at all. Sometimes it is a continual vision of possibilities: “My enemy is coming and I’m hitting him—I want war.” Or, “My friend is coming, I’m hugging him, welcoming him to my house, giving him hospitality.” It goes on all the time. “I have a desire to eat lambchops—no, leg of lamb, steak, lemon ice cream. My friend and I could go out to the shop and get some ice cream and bring it home and have a nice conversation over ice cream. We could go to that Mexican restaurant and get tacos ‘to go’ and bring them back home. We’ll dip them in the sauce and eat together and have a nice philosophical discussion as we eat. Nice to do that with candlelight and soft music.” We are constantly dreaming of infinite possibilities for all kinds of entertainment. There is no room to stop, no room to start providing space. Providing space: effort, noneffort and effort, noneffort—it’s very choppy in a sense, very precise, knowing how to release the discursive or visionary gossip. Right effort—it’s beautiful.

The next one is “right mindfulness.” Right mindfulness does not simply mean being aware; it is like creating a work of art. There is more spaciousness in right mindfulness than in right effort. If you are drinking a cup of tea, you are aware of the whole environment as well as the cup of tea. You can therefore trust what you are doing, you are not threatened by anything. You have room to dance in the space, and this makes it a creative situation. The space is open to you.

The eighth aspect of the eightfold path is “right samadhi,” right absorption. Samadhi has the sense of being as it is, which means relating with the space of a situation. This pertains to one’s living situation as well as to sitting meditation. Right absorption is being completely involved, thoroughly and fully, in a nondualistic way. In sitting meditation the technique and you are one; in life situations the phenomenal world is also part of you. Therefore you do not have to meditate as such, as though you were a person distinct from the act of meditating and the object of meditation. If you are one with the living situation as it is, your meditation just automatically happens.

SIX

The Open Way

T

HE

B

ODHISATTVA

V

OW

B

EFORE WE COMMIT

ourselves to walking the bodhisattva path, we must first walk the hinayana or narrow path. This path begins formally with the student taking refuge in the buddha, the dharma, and the sangha—that is, in the lineage of teachers, the teachings, and the community of fellow pilgrims. We expose our neurosis to our teacher, accept the teachings as the path, and humbly share our confusion with our fellow sentient beings. Symbolically, we leave our homeland, our property and our friends. We give up the familiar ground that supports our ego, admit the helplessness of ego to control its world and secure itself. We give up our clingings to superiority and self-preservation. But taking refuge does not mean becoming dependent upon our teacher or the community or the scriptures. It means giving up searching for a home, becoming a refugee, a lonely person who must depend upon himself. A teacher or fellow traveler or the scriptures might show us where we are on a map and where we might go from there, but we have to make the journey ourselves. Fundamentally, no one can help us. If we seek to relieve our loneliness, we will be distracted from the path. Instead, we must make a relationship with loneliness until it becomes aloneness.

In the hinayana the emphasis is on acknowledging our confusion. In the mahayana we acknowledge that we are a buddha, an awakened one, and act accordingly, even though all kinds of doubts and problems might arise. In the scriptures, taking the bodhisattva vow and walking on the bodhisattva path is described as being the act of awakening bodhi or “basic intelligence.” Becoming “awake” involves seeing our confusion more clearly. We can hardly face the embarrassment of seeing our hidden hopes and fears, our frivolousness and neurosis. It is such an overcrowded world. And yet it is a very rich display. The basic idea is that, if we are going to relate with the sun, we must also relate with the clouds that obscure the sun. So the bodhisattva relates positively to both the naked sun and the clouds hiding it. But at first the clouds, the confusion, which hide the sun are more prominent. When we try to disentangle ourselves, the first thing we experience is entanglement.

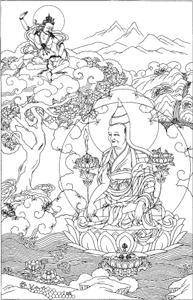

Longchenpa (Klong chen rab byams pa) with Shri Simha above his head. Longchenpa was a great teacher of the Nyingma lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. He is known for systematizing the oral teachings of this lineage. Shri Simha was an Indian master of the highest teachings of tantra. He was a teacher of Padmasambhava, who brought the buddhadharma to Tibet.

DRAWING BY GLEN EDDY.

The stepping-stone, the starting point in becoming awake, in joining the family of buddhas, is the taking of the bodhisattva vow. Traditionally, this vow is taken in the presence of a spiritual teacher and images of the buddhas and the scriptures in order to symbolize the presence of the lineage, the family of Buddha. One vows that from today until the attainment of enlightenment I devote my life to work with sentient beings and renounce my own attainment of enlightenment. Actually we cannot attain enlightenment until we give up the notion of “me” personally attaining it. As long as the enlightenment drama has a central character, “me,” who has certain attributes, there is no hope of attaining enlightenment because it is nobody’s project; it is an extraordinarily strenuous project but nobody is pushing it. Nobody is supervising it or appreciating its unfolding. We cannot pour our being from our dirty old vessel into a new clean one. If we examine our old vessel, we discover that it is not a solid thing at all. And such a realization of egolessness can only come through the practice of meditation, relating with discursive thoughts and gradually working back through the five skandhas. When meditation becomes an habitual way of relating with daily life, a person can take the bodhisattva vow. At that point discipline has become ingrown rather than enforced. It is like becoming involved in an interesting project upon which we automatically spend a great deal of time and effort. No one needs to encourage or threaten us; we just find ourselves intuitively doing it. Identifying with buddha nature is working with our intuition, with our ingrown discipline.

The bodhisattva vow acknowledges confusion and chaos—aggression, passion, frustration, frivolousness—as part of the path. The path is like a busy, broad highway, complete with roadblocks, accidents, construction work, and police. It is quite terrifying. Nevertheless it is majestic, it is the great path. “From today onward until the attainment of enlightenment I am willing to live with my chaos and confusion as well as with that of all other sentient beings. I am willing to share our mutual confusion.” So no one is playing a one-upmanship game. The bodhisattva is a very humble pilgrim who works in the soil of samsara to dig out the jewel embedded in it.

H

EROISM

The bodhisattva path is a heroic path. In the countries in which it developed—Tibet, China, Japan, Mongolia—the people are rugged, hardworking and earthy. The style of practice of the mahayana reflects the heroic qualities of these people—the Japanese samurai tradition, the industriousness of the Chinese peasant, the Tibetan struggle with barren, forbidding land. However, in America the ruggedly heroic approach to practice of these peoples is often translated and distorted into a rigid militantism, a robotlike regimentation. The original approach involved the delight of feeling oneself invincible, of having nothing to lose, of being completely convinced of your aloneness. Sometimes, of course, beginning bodhisattvas have second thoughts about such a daring decision to abandon enlightenment and throw themselves to the mercy of sentient beings and work with them, taking delight and pride in compassionate action. They become frightened. This hesitation is described metaphorically in the sutras as standing in the doorway of your house, having one foot out in the street and the other foot inside the house. That moment is the test of whether you go beyond the hesitation and step out into the no-man’s-land of the street or decide to step back into your familiar home ground, of whether you are willing to work for the benefit of all sentient beings or wish to indulge yourself in the arhat mentality of self-enlightenment.

The preparation for the bodhisattva path is the unification of body and mind: the body works for the mind and the mind works for the body. The hinayana shamatha and vipashyana practices make the mind precise, tranquil, and smooth in the positive sense—precisely being there, rather than dreaming or sleeping or hazily perceiving. We can make a cup of tea properly, cook sunny-side-up properly, serve food properly, because the body and mind are synchronized.