The Complete Guide to English Spelling Rules (3 page)

Read The Complete Guide to English Spelling Rules Online

Authors: John J Fulford

Noah Webster was the first lexicographer to attempt to bring some kind of order to English spelling. His arguments were based on a thorough knowledge of the subject and laced with a heavy dose of common sense. In the preface to

his

Compendious Dictionary of the English Language,

he took great pains to explain his reasoning. Let us use his words to look first at the

centre-center, theatre-theater

problem.

We have a few words of another class which remain as outlaws in orthography. These are such as end in

re,

as

sceptre, theatre, metre, mitre, nitre, lustre, sepulchre, spectre,

and a few others.... It is among the inconsistencies which meet our observation in every part of orthography that the French

nombre, chambre, disastre, disordre,

etc. … should be converted into number, chamber, disaster, disorder, etc. confirmable to the pronunciation, and that

lustre, sceptre, metre,

and a few others should be permitted to wear their foreign livery

3

.

The difference between Dr. Johnson and Noah Webster is clear. The former was primarily interested in the meaning of the words and their correct usage. To Dr. Johnson, the spelling was of little importance. The practical American, on the other hand, while stressing correct usage, was very interested in correct pronunciation and spelling.

He supports this statement by pointing out that the great English writers Newton, Dryden, Shaftsbury, Hook, Middleton, et al., wrote these words in the “regular English manner.”

Further on, Webster writes:

The present practice is not only contrary to the general uniformity... but is inconsistent with itself; for Peter, a proper name, is always written in the English manner; while

salt petre,

the word, derived from the same original, is written in the French manner

. Metre

also retains its French spelling, while the same word in composition, as in diameter, barometer, and thermometer, is conformed to the English orthography. Such palpable inconsistencies and preposterous anomalies do no honor to English literature, but very much perplex the student, and offend the man of taste.

4

From this, we can see that Webster, far from demanding radical change, was only insisting that English spelling conform to historical spelling rules. He was actually very conservative.

We may again use Noah Webster’s own words in the problem of

labor-labour

and

honor-honour :

To purify our orthography from corruptions and restore to words their genuine spelling, we ought to reject

u

from honor, candor, error, and others of this class. Under the Norman princes... to preserve a trace of their originals, the

o

of the Latin honor, as well as the

u

of the French honeur was retained... our language was disfigured with a class of mongrels. splendour, inferiour, superiour, authour, and the like, which are neither Latin nor French, nor calculated to exhibit the English pronunciation.

5

Noah Webster was the first lexicographer to attempt to bring some kind of order to English spelling.

He continues:

The palpable absurdity of inserting

u

in primitive words, when it must be omitted in the derivations, superiority, inferiority, and the like; for no person ever wrote superiourity, inferiourity...

6

Again we can see that Webster was demanding conformity in spelling including a strict adherence to the basic rules, for, as he wrote in an earlier paragraph, “Uniformity is a prime excellence in the rules of language.”

Another interesting difference between English and American spelling is the double

l

. The spelling rule for doubling the consonant when adding a suffix is quite clear. Part of the rule states that in words of more than one syllable, the final consonant shall not be doubled unless the accent falls on the final syllable. For example,

regret–regretted

. British spelling adheres to this rule except when the word ends in an

l

. Then, for some yet to be explained reason, the rule is abandoned and the

l

is doubled no matter where the accent happens to be. For example,

travel–travelled

. This double

l

can be seen in other strange places, such as,

chili–chilli, woolen–woollen

.

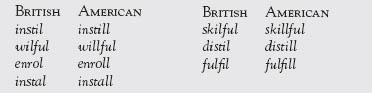

However, there are at least half a dozen cases where the situation is reversed and the British spell the word with only one l, while the Americans, for no logical reason, spell it with two. For example:

Noah Webster would have had something quite scathing to say about “such palpable inconsistencies and preposterous anomalies.”

In American spelling, there is a conscious attempt to simplify while retaining the correct sound and meaning, especially in the case of multiple letters. British English still retains numerous examples of double consonants where a single consonant would be quite sufficient, for example,

worshipping

and

focuss

. American simplification extends especially to triple vowels. Whether they are diphthongs or not, we feel that two vowels should be enough to produce the desired sound. Fortunately, many of the British triple vowel words are slowly disappearing, for example,

diarrhoea–diarrhea

and

manoeuvre–maneuver

. Retaining an unneeded and unhelpful extra letter is illogical when we remember that the prime function of language is clear communication.

Since Noah Webster’s time there have been a number of attempts to reform, or at least to improve, English spelling. They vary from the thoughtful to the ludicrous. At the present time there is a widespread belief that perhaps English spelling could be made more phonetic, despite the fact that English is not a completely phonetic language. Roughly half of our words are already spelled phonetically, but the other half could never be spelled according to the rules of phonics without utter chaos. In the words of the great writer Jonathan Swift,

Another cause ... which hath contributed not a little to the maiming of our language, is a foolish Opinion, advanced of late years, that we ought to spell exactly as we speak, which besides the obvious inconvenience of utterly destroying our Etymology, would be a thing we should never see the end of

.

7

This is not to say that spelling is sacrosanct and should never be allowed to change; on the contrary, our spelling is constantly changing, sometimes at glacial speed, other times quite rapidly. But not all change is for the better. A change in spelling is acceptable if it purges the original word of superfluous letters or illogical construction. Simplification is to be encouraged only if it does not change the meaning of the original word in any way. It is imperative that the new

spelling conform to the spelling rules and that it resemble the original word as closely as possible. Care should be taken to try to avoid the creation of yet another homophone or homograph.

Many attempts to reform English spelling have been targeted at the alphabet. George Bernard Shaw left the bulk of his fortune to a committee charged with producing a better alphabet, but with no success. On the other hand, the 19th century geniuses who produced the International Phonetic Alphabet were very successful and the IPA, has proved immensely valuable.

Probably the most famous person to tackle the problem was Benjamin Franklin. Although he was a friend of Noah Webster and an enthusiastic supporter of Webster’s work, he was much more radical than Webster. Franklin designed an alphabet containing six new letters, and he eliminated the

c

in favor of the

s

and the

k

. He showed his specially carved type to Webster, but Webster declined to use it. Initially, Webster had proposed quite a few revolutionary changes to English spelling, but the resistance that he encountered soon persuaded him that the average person was—and still is—not prepared to accept extraordinary changes to his or her mother tongue. Although Webster gradually modified his suggestions, quite a large number of his improvements were eventually accepted on both sides of the Atlantic.