The Complete Guide to English Spelling Rules (6 page)

Read The Complete Guide to English Spelling Rules Online

Authors: John J Fulford

(1) A change in spelling is acceptable if it purges the original word of superfluous letters or illogical construction.

(2) Simplification is to be encouraged only if it does not change the meaning in any way or create yet another homophone or homograph.

(3) In all cases it is imperative that the new spelling conform to the spelling rules.

(4) “...and that it resemble, as closely as possible, the original word.

(1) “A change in spelling is acceptable if it purges the original word of superfluous letters or illogical construction.”

It is clear that the reformers did this, often with excessive enthusiasm.

(2) “Simplification is to be encouraged only if it does not change the meaning in any way or create yet another homophone or homograph.”

Here the reformers made too many mistakes. Considering the high quality of the academics who made up most of the committees, it is truly astonishing the number of times that the reformed word was simply a homonym and bound to cause confusion.

(

3) “In all cases it is imperative that the new spelling conform to the spelling rules.”

It is all too clear that the spelling rules were largely ignored by the reformers. Perhaps they saw these rules as traditions that had to be broken in order to get the job done, or perhaps they hoped to create new spelling rules that were more logical. Whatever their reasoning, it is clear that they wasted little effort attempting to make their spellings conform to the traditional English spelling rules.

(4) “...and that it resemble, as closely as possible, the original word.”

In this vital matter, the reformers failed completely. There was little if any attempt to cater to the “visual prejudice” of the general public. Too many of the new words appear ungainly, awkward, and down right ugly. Many are so different in appearance that the reader has to pause a while in order to assimilate them. When all things are considered, it is probably this last factor that was mainly responsible for the lack of interest shown by the general public and the ultimate decline of the reform movement.

There is little doubt that elitism and snobbery were important factors in the defeat of the spelling reformers. At the time the reformers were working, the great cities of the eastern United States were swarming with new immigrants, most of whom were low-class laborers with just a smattering of English. In England and in America, the people who migrated to the cities from rural areas were hardly much better, as few had much education.

It can take up to twenty years for a person to acquire a near perfect grasp of English, and it usually takes both time and money, two things not available to the average working man at that time. The result was a small but powerful elite that read books, newspapers, and journals and prided itself on the ability to use both the spoken and the written word with ease and skill. The standard of literacy and fluency was very high indeed—for the few. This is not to say that it was only the children of the rich and powerful who were well educated. History is full of examples of men and women of very humble origins who acquired a near perfect grasp of the English language through extraordinary perseverance. Abraham Lincoln is an excellent example.

But the common working man, who was most in need of a better education, was not asked for his opinion of the work of the spelling reformers. The most violent criticism of reform came from newspaper editors, writers, and statesmen, all of whom saw it as an attack on that which they valued the most—their excellent grasp of English and their hard earned knowledge of its intricacies and subtleties. We could compare this resistance to the medieval guild masters protecting their craft and craftsmen from interlopers.

Today, when literacy is all but universal, we can look back with some astonishment at the way in which spelling reform was rejected and the virulence of those who opposed it. But has one short century made much difference? There is still a great deal of elitism involved in the use of English. One small grammatical error can lower a speaker in the eye of his listener; a little mispronunciation or the wrong accent can do the same. Poor sentence structure can ruin even the best article or e-mail, whereas the clever use of words can make the poorest argument sound convincing.

As for spelling, there is an almost primitive defensive reaction to any spelling mistake discovered in our morning newspaper. We are angry and indignant when we see spelling mistakes in any printed document, whether it is an official

publication or merely a hand-delivered leaflet. This reaction occurs just as readily when the misspelled word is one of those ludicrous, illogical, un-phonetic words that should have been “reformed” centuries ago.

There are numerous publications that refuse to use any “modern” spelling. The editors seem to think that

analogue

is superior to

analog,

that

archaeology

with three vowels in a row is more correct than

archeology

with only two, and they shudder at

thru

and

lite

. Unfortunately, such reactionary thinking is not uncommon, even though it is historically and etymologically false and any attempt to radically “improve” English spelling will surely be met by stiff resistance based largely on visual prejudice. In the preface to his 1806 edition, Noah Webster wrote,

The opposers of reform, on the other hand, contend that no alterations should be made in orthography, as they would ... occasion inconvenience.... It is fortunate for the language and for those who use it, that this doctrine did not prevail in the reign of Henry the Fourth ... had all changes in spelling ceased at that period, what a spectacle of deformity would our language now exhibit! Every man ... knows that a living language must necessarily suffer gradual changes in its current words, and in pronunciation ... strange as it may seem the fact is undeniable, that the present doctrine that no change must be made in writing words, is destroying the benefits of an alphabet, The correct principal respecting changes in orthography seems to lie between these extremes of opinion. No great changes shall be made at once... But gradual changes to accommodate the written to the spoken language ... and especially when they purify words from corruptions...are not only proper but indispensable

.

8

Throughout this book, I use the phrase “commonly used words.” This needs a little explanation. The English language contains over half a million words, more than any other European language, and new words appear almost daily as old words change or disappear. No one person could

be familiar with the entire vocabulary. While the average educated person uses only a tiny fraction of these words, he or she is familiar with, and will recognize, a much greater number. Although the words used in this book can be found in any good dictionary, I have attempted to keep to a bare minimum the use of names, technical and scientific terms, and rare or obscure words.

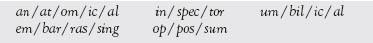

I use the terms “stem” and “root” when referring to the basic word before affixes have been added. In the majority of cases, the stems will be recognizable words, but, over time, many of these words have vanished or been drastically changed, and yet the stem with its affix has remained. For example, we use the words invoke, provoke, and revoke, and it is clear that the in, pro, and re are prefixes. But the root word voke no longer exists.

C

lear and careful pronunciation is of immense value when one is faced with a spelling problem. Breaking a word into its component syllables is the best approach to clear pronunciation, which brings us to the question, just what is the correct way to divide a word into syllables?

Most dictionaries, texts, and guides are quite useless, as there are both complete confusion and numerous contradictions. If we look up a word in three different guides, we will probably get three different choices, sometimes four. This is unfortunate because correct syllabification is a great help to both correct pronunciation and correct spelling.

Words are merely sounds strung together to form recognizable combinations. The heart of each sound is a vowel or diphthong. The vowel sound will be either short or long, and each syllable must contain the vowel or diphthong plus the consonants that give it that particular sound. Let us look at the short vowel sound first.

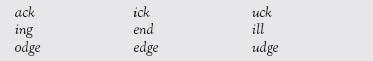

Spelling rule #1: Closed syllables consist of a vowel followed by a consonant.

They are almost always short vowels.

In a closed syllable the vowel may be followed by two or more consonants and still retain the short vowel sound.

Note that these blends or digraphs form an essential part of the syllable and must remain with the vowel.

With double consonants, the division is between the two consonants unless they are at the end of the word. Never split a blend or digraph.