The Complete Yes Minister (20 page)

He then went on to say that it is

his

job to run the Department. And that my job is to make policy, get legislation enacted and – above all – secure the Department’s budget in Cabinet.

his

job to run the Department. And that my job is to make policy, get legislation enacted and – above all – secure the Department’s budget in Cabinet.

‘Sometimes I suspect,’ I said to him, ‘that the budget is all you really care about.’

‘It is rather important,’ he answered acidly. ‘If nobody cares about the budget we could end up with a Department so small that even a Minister could run it.’

I’m sure he’s not supposed to speak to me like this.

However, I wasn’t upset because I’m sure of my ground. ‘Humphrey,’ I enquired sternly, ‘are we about to have a fundamental disagreement about the nature of democracy?’

As always, he back-pedalled at once when seriously under fire. ‘No, Minister,’ he said in his most oily voice, giving his now familiar impression of Uriah Heep, ‘we are merely having a demarcation dispute. I am only saying that the menial chore of running a Department is beneath you. You were fashioned for a nobler calling.’

Of course, the soft soap had no effect on me. I insisted on action, now! To that end, we left it that he would look at my reorganisation plan. He promised to do his best to put it into practice, and will set up a committee of enquiry with broad terms of reference so that at the end of the day we can take the right decisions based on long-term considerations. He argued that this was preferable to rushing prematurely into precipitate and possibly ill-conceived actions which might have unforeseen repercussions. This seems perfectly satisfactory to me; he has conceded the need for wide-ranging reforms, and we might as well be sure of getting them right.

Meanwhile, while I was quite happy to leave all the routine paperwork to Humphrey and his officials, from now on I was to have direct access to

all

information. Finally, I made it clear that I never again wished to hear the phrase, ‘there are some things it is better for a Minister not to know.’

all

information. Finally, I made it clear that I never again wished to hear the phrase, ‘there are some things it is better for a Minister not to know.’

February 20th

Saturday today, and I’ve been at home in the constituency.

I’m very worried about Lucy. [

Hacker’s daughter, eighteen years old at this time – Ed

.] She really does seem to be quite unbalanced sometimes. I suppose it’s all my fault. I’ve spent little enough time with her over the years, pressure of work and all that, and it’s obviously no coincidence that virtually all my successful colleagues in the House have highly acrimonious relationships with their families and endlessly troublesome adolescent children.

Hacker’s daughter, eighteen years old at this time – Ed

.] She really does seem to be quite unbalanced sometimes. I suppose it’s all my fault. I’ve spent little enough time with her over the years, pressure of work and all that, and it’s obviously no coincidence that virtually all my successful colleagues in the House have highly acrimonious relationships with their families and endlessly troublesome adolescent children.

But it can’t all be my fault.

Some

of it must be her own fault! Surely!

Some

of it must be her own fault! Surely!

She was out half the night and came down for a very late breakfast, just as Annie and I were starting an early lunch. She picked up the

Mail

with a gesture of disgust – solely because it’s not the

Socialist Worker

, or

Pravda

, I suppose.

with a gesture of disgust – solely because it’s not the

Socialist Worker

, or

Pravda

, I suppose.

I had glanced quickly through all the papers in the morning, as usual, and a headline on a small story on an inside page of

The Guardian

gave me a nasty turn. HACKER THE BADGER BUTCHER. The story was heavily slanted against me and in favour of the sentimental wet liberals – not surprising really, every paper has to pander to its typical reader.

The Guardian

gave me a nasty turn. HACKER THE BADGER BUTCHER. The story was heavily slanted against me and in favour of the sentimental wet liberals – not surprising really, every paper has to pander to its typical reader.

Good old

Grauniad

.

Grauniad

.

I nobly refrained from saying to Lucy, ‘Good afternoon’ when she came down, and from making a crack about a sit-in when she told us she’d been having a lie-in.

However, I

did

ask her why she was so late home last night, to which she replied, rather pompously, ‘There are some things it is better for a father not to know.’ ‘Don’t

you

start,’ I snapped, which, not surprisingly, puzzled her a little.

did

ask her why she was so late home last night, to which she replied, rather pompously, ‘There are some things it is better for a father not to know.’ ‘Don’t

you

start,’ I snapped, which, not surprisingly, puzzled her a little.

She told me she’d been out with the trots. I was momentarily sympathetic and suggested she saw the doctor. Then I realised she meant the Trotskyites. I’d been slow on the uptake because I didn’t know she was a Trotskyite. Last time we talked she’d been a Maoist.

‘Peter’s a Trot,’ she explained.

‘Peter?’ My mind was blank.

‘You’ve only met him about fifteen times,’ she said in her most scathing tones, the voice that teenage girls specially reserve for when they speak to their fathers.

Then Annie, who could surely see that I was trying to work my way through five red boxes this weekend, asked me to go shopping with her at the ‘Cash and Carry’, to unblock the kitchen plughole, and mow the lawn. When I somewhat irritably explained to her about the boxes, she said they could wait!

‘Annie,’ I said, ‘it may have escaped your notice that I am a Minister of the Crown. A member of Her Majesty’s Government. I do a

fairly

important job.’

fairly

important job.’

Annie was strangely unsympathetic. She merely answered that I have twenty-three thousand civil servants to help me, whereas she had none. ‘You can play with your memos later,’ she said. ‘The drains need fixing now.’

I didn’t even get round to answering her, as at that moment Lucy stretched across me and spilled marmalade off her knife all over the cabinet minutes. I tried to scrape it off, but merely succeeded in buttering the minutes as well.

I told Lucy to get a cloth, a simple enough request, and was astounded by the outburst that it provoked. ‘Get it yourself,’ she snarled. ‘You’re not in Whitehall now, you know. “Yes Minister” . . . “No Minister” . . . “Please may I lick your boots, Minister?”’

I was speechless. Annie intervened on my side, though not as firmly as I would have liked. ‘Lucy, darling,’ she said in a tone of mild reproof, ‘that’s not fair. Those civil servants are always kowtowing to Daddy, but they never take any real notice of him.’

This was too much. So I explained to Annie that only two days ago I won a considerable victory at the Department. And to prove it I showed her the pile of five red boxes stuffed full of papers.

She didn’t think it proved anything of the sort. ‘For a short while you were getting the better of Sir Humphrey Appleby, but now they’ve snowed you under again.’

I thought she’d missed the point. I explained my reasoning: that Humphrey had said to me,

in so many words

, that there are some things that it’s better for a Minister not to know, which means that he hides things from me. Important things, perhaps. So I have now insisted that I’m told

everything

that goes on in the Department.

in so many words

, that there are some things that it’s better for a Minister not to know, which means that he hides things from me. Important things, perhaps. So I have now insisted that I’m told

everything

that goes on in the Department.

However, her reply made me rethink my situation. She smiled at me with genuine love and affection, and said:

‘Darling, how did you get to be a Cabinet Minister? You’re such a clot.’

Again I was speechless.

Annie went on, ‘Don’t you see, you’ve played right into his hands? He must be utterly delighted. You’ve given him an open invitation to swamp you with useless information.’

I suddenly saw it all with new eyes. I dived for the red boxes – they contained feasibility studies, technical reports, past papers of assorted committees, stationery requisitions . . . junk!

It’s Catch-22. Those bastards. Either they give you so little information that you don’t know the facts, or so much information that you can’t

find

them.

find

them.

You can’t win. They get you coming and going.

February 21st

The contrasts in a Minister’s life are supposed by some people to keep you sane and ordinary and feet-on-the-ground. I think they’re making me schizoid.

All week I’m protected and cosseted and cocooned. My every wish is somebody’s command. (Not on matters of real substance of course, but in little everyday matters.) My letters are written, my phone is answered, my opinion is sought, I’m waited on hand and foot and I’m driven everywhere by chauffeurs, and everyone addresses me with the utmost respect as if I were a kind of God.

But this is all on government business. The moment I revert to party business or private life, the whole apparatus deserts me. If I go to a party meeting, I must get myself there, by bus if necessary; if I go home on constituency business, no secretary accompanies me; if I have a party speech to make, there’s no one to type it out for me. So every weekend I have to adjust myself to doing the washing up and unblocking the plughole after five days of being handled like a priceless cut-glass antique.

And this weekend, although I came home on Friday night on the train, five red boxes arrived on Saturday morning in a chauffeur-driven car!

Today I awoke, having spent a virtually sleepless night pondering over what Annie had said to me. I staggered down for breakfast, only to find – to my amazement – a belligerent Lucy lying in wait for me. She’d found yesterday’s

Guardian

and had been reading the story about the badgers.

Guardian

and had been reading the story about the badgers.

‘There’s a story about you here, Daddy,’ she said accusingly.

I said I’d read it. Nonetheless she read it out to me. ‘Hacker the badger butcher,’ she said.

‘Daddy’s read it, darling,’ said Annie, loyally. As if stone-deaf, Lucy read the whole story aloud. I told her it was a load of rubbish, she looked disbelieving, so I decided to explain in detail.

‘One: I am not a badger butcher. Two: the badger is not an endangered species. Three: the removal of protective status does not necessarily mean the badgers will be killed. Four: if a few badgers have to be sacrificed for the sake of a master plan that will save Britain’s natural heritage – tough!’

Master plan is always a bad choice of phrase, particularly to a generation brought up on Second World War films. ‘Ze master plan, mein Führer,’ cried my darling daughter, giving a Nazi salute. ‘Ze end justifies ze means, does it?’

Apart from the sheer absurdity of a supporter of the Loony Left having the nerve to criticise someone

else

for believing that the end justifies the means – which I don’t or not necessarily, anyway – she is really making a mountain out of a ridiculous molehill.

else

for believing that the end justifies the means – which I don’t or not necessarily, anyway – she is really making a mountain out of a ridiculous molehill.

‘It’s because badgers haven’t got votes, isn’t it?’ This penetrating question completely floored me. I couldn’t quite grasp what she was on about.

‘If badgers had votes you wouldn’t be exterminating them. You’d be up there at Hayward’s Spinney, shaking paws and kissing cubs. Ingratiating yourself the way you always do. Yuk!’

Clearly I have not succeeded in ingratiating myself with my own daughter.

Annie intervened again. ‘Lucy,’ she said, rather too gently I thought, ‘that’s not a very nice thing to say.’

‘But it’s true, isn’t it?’ said Lucy.

Annie said: ‘Ye-e-es, it’s true . . . but well, he’s in politics. Daddy

has

to be ingratiating.’

has

to be ingratiating.’

Thanks a lot.

‘It’s got to be stopped,’ said Lucy. Having finished denouncing me, she was now instructing me.

‘Too late.’ I smiled nastily. ‘The decision’s been taken, dear.’

‘I’m going to stop it, then,’ she said.

Silly girl. ‘Fine,’ I said. ‘That should be quite easy. Just get yourself adopted as a candidate, win a general election, serve with distinction on the back benches, be appointed a Minister and repeal the act. No problem. Of course, the badgers might be getting on a bit by then.’

She flounced out and, thank God, stayed out for the rest of the day.

[

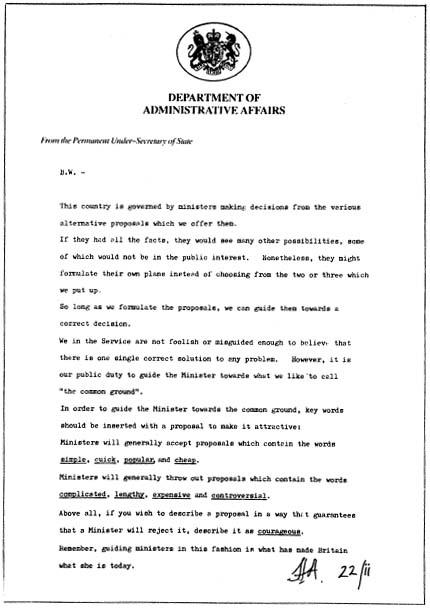

Meanwhile, Bernard Woolley was becoming increasingly uneasy about keeping secrets from the Minister. He was finding it difficult to accustom himself to the idea that civil servants apply the ‘need to know’ principle that is the basis of all security activities. Finally he sent a memo to Sir Humphrey, asking for a further explanation as to why the Minister should not be allowed to know whatever he wants to know. The reply is printed below – Ed

.]

Meanwhile, Bernard Woolley was becoming increasingly uneasy about keeping secrets from the Minister. He was finding it difficult to accustom himself to the idea that civil servants apply the ‘need to know’ principle that is the basis of all security activities. Finally he sent a memo to Sir Humphrey, asking for a further explanation as to why the Minister should not be allowed to know whatever he wants to know. The reply is printed below – Ed

.]

[

It is worth examining Sir Humphrey Appleby’s choice of words in this memo. The phrase ‘the common ground’, for example, was much used by senior civil servants after two changes in government in the first four years of the 1970s. It seemed to mean policies that the Civil Service can pursue without disturbance to the party in power. ‘Courageous’ as used in this context is an even more damning word than ‘controversial’. ‘Controversial’ only means ‘this will lose you votes’. ‘Courageous’ means ‘this will lose you the election’ – Ed

.]

It is worth examining Sir Humphrey Appleby’s choice of words in this memo. The phrase ‘the common ground’, for example, was much used by senior civil servants after two changes in government in the first four years of the 1970s. It seemed to mean policies that the Civil Service can pursue without disturbance to the party in power. ‘Courageous’ as used in this context is an even more damning word than ‘controversial’. ‘Controversial’ only means ‘this will lose you votes’. ‘Courageous’ means ‘this will lose you the election’ – Ed

.]

Other books

Beyond Reach by Melody Carlson

Brushed by Scandal by Gail Whitiker

Hidden (Book 1) by Megg Jensen

Archangel's Shadows by Nalini Singh

Trinidad Street by Patricia Burns

Bounty Hunter 2: Redemption by Joseph Anderson

The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris by David Mccullough

The Imprisoned Dragon and the Witch by A K Michaels

Fledgling (The Dragonrider Chronicles) by Conway, Nicole

Access to Power by Ellis, Robert