The Computers of Star Trek (7 page)

Read The Computers of Star Trek Online

Authors: Lois H. Gresh

It's evident from a number of episodes that this constant exchange of information doesn't take place. Otherwise, Data's experiment with Lal (“The Offspring,”

TNG

) would never occur.

Nor would the crew be able to promise the Paxans that their existence would be kept secret (“Clues,”

TNG

). It's most likely that at specific intervals, a subspace transmission of data is sent from Federation starships to fleet headquarters. And that similar transmissions are made from headquarters to all ships, updating computer records and databases.

Distributed Processing NetworkTNG

) would never occur.

Nor would the crew be able to promise the Paxans that their existence would be kept secret (“Clues,”

TNG

). It's most likely that at specific intervals, a subspace transmission of data is sent from Federation starships to fleet headquarters. And that similar transmissions are made from headquarters to all ships, updating computer records and databases.

T

he final component of the

Enterprise's

computer system is the distributed processing network (

DPN

). This is supposedly a network of “dedicated optical links” distributed all over the ship “to augment the main cores.” The DPN does not use the FTL core elements. It “improves overall system response” and also provides redundancy for emergency situations.

he final component of the

Enterprise's

computer system is the distributed processing network (

DPN

). This is supposedly a network of “dedicated optical links” distributed all over the ship “to augment the main cores.” The DPN does not use the FTL core elements. It “improves overall system response” and also provides redundancy for emergency situations.

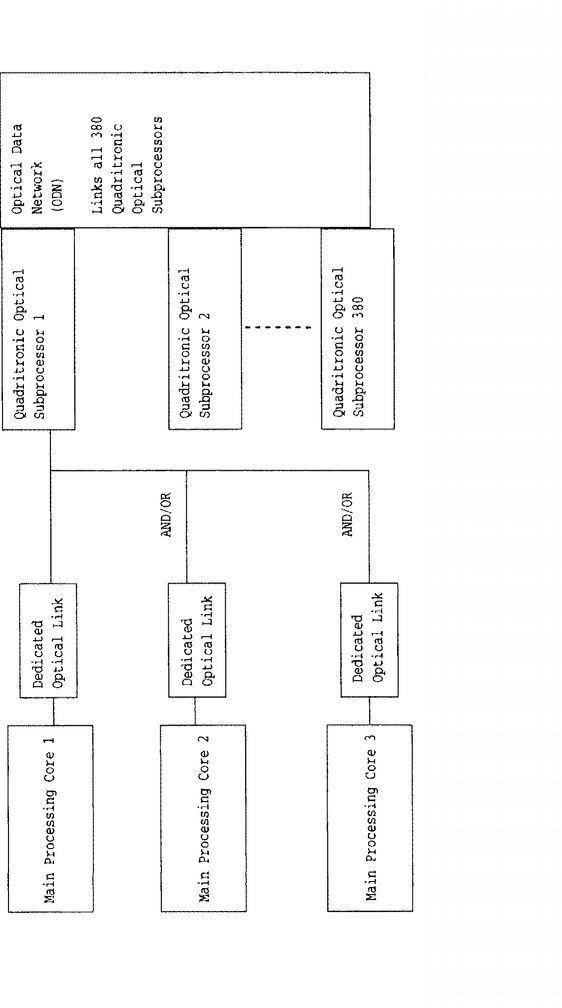

Each quadritronic optical subprocessor (QOS) accesses from one to three main processing cores via a dedicated optical link (as shown in

Figure 2.7

). The technical manual doesn't explain anything about the QOS nor the overall DPN architecture.

Figure 2.7

). The technical manual doesn't explain anything about the QOS nor the overall DPN architecture.

Frankly, neither the QOS nor DPN makes sense.

The manual states that if the main computer system crashes, some QOS/DPN backup mechanism keeps the ship running. Let's assume that the main computer system does crash. It happens to fuel the optical data networkâthat is, without the main computer system, the ODN crashes, too. This architecture offers no redundancy for emergency situations. The manual states that the quadritronic optical subprocessors are part of the optical data network. If the ODN dies, then all the quadritronic optical subprocessors die. Who cares if there are dedicated optical links from each QOS to the main computer? The whole system is down.

And if the main processing cores are all dead, perhaps the LCARS is dead as well.

FIGURE 2.7

Distributed Processing Network (DPN)

Distributed Processing Network (DPN)

Further, if the DPN isn't running at FTL, for whatever that's worth, how does it “improve overall system response”?

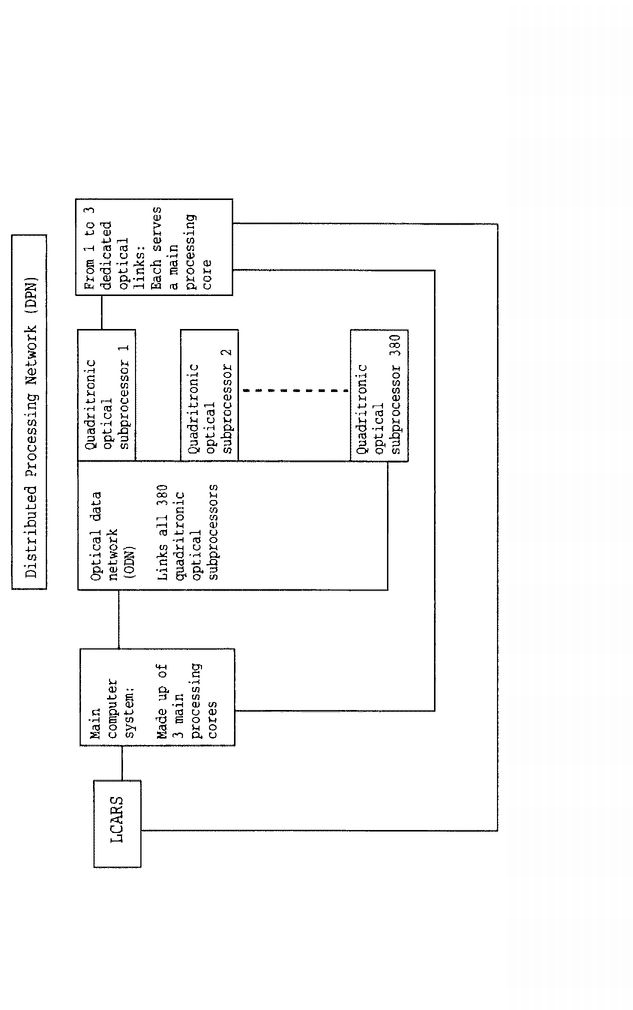

To determine if any of this makes sense, we'll merge

Figure 2.1

with

Figure 2.7

. The result is

Figure 2.8

.

Figure 2.1

with

Figure 2.7

. The result is

Figure 2.8

.

The LCARS is hooked directly to the main computer system and the dedicated optical links. The dedicated optical links, in turn, hook directly to the ODN. If the main computer system crashes, the ODN crashes. (Face it, folks: if the system dies, there's nothing left to run the network. Where's the operating system? In the main computer.) There is no point to the dedicated optical links. If the main computer system and the ODN crash, then the optical links also die. The LCARS may function as standalone processors, providing some small amount of backup data. Neither the technical manual nor the actual TV shows indicate that this occurs.

We see no point to the DPN. It is illogical.

Personal Access Display DevicesI

n chapter 1 we discussed communicators and what appear to be laptop computers on

TNG

,

VGR

, and

DS9

. We'll close with a brief look at PADDs.

n chapter 1 we discussed communicators and what appear to be laptop computers on

TNG

,

VGR

, and

DS9

. We'll close with a brief look at PADDs.

In the original series, PADDs were the size of clipboards and appeared to serve a similar purpose. Their resemblance to portable computers was minimal. In

The Next Generation

, PADDs had shrunk in size and gained in power to become handheld computers directly linked to the ship's computer. A PADD serves not only as a personal computer but also as a communication device and even a lock-on node from the starship's transporter. According to the

Technical Manual,

a PADD has a dimension of 10 X 15 X 1 centimeter and a total memory capacity of 4.3 kiloquads (that is, 4.3 times the total information now stored on Earth). In theory, a crewmember using a PADD with the proper access codes could navigate the starship from his quarters.

The Next Generation

, PADDs had shrunk in size and gained in power to become handheld computers directly linked to the ship's computer. A PADD serves not only as a personal computer but also as a communication device and even a lock-on node from the starship's transporter. According to the

Technical Manual,

a PADD has a dimension of 10 X 15 X 1 centimeter and a total memory capacity of 4.3 kiloquads (that is, 4.3 times the total information now stored on Earth). In theory, a crewmember using a PADD with the proper access codes could navigate the starship from his quarters.

FIGURE 2.8

DPN and ODN

DPN and ODN

Again we find science overtaking science fiction. The past few years have seen the rise of handheld computers only slightly bigger than a PADD and with many of the same features. These devices continue to shrink, and computers the size of watches are already available. Life imitates art, then surpasses it. Why carry around a PADD when molecular implants will allow you to converse with invisible computers in the wall? It's in the future, and not three hundred years from now.

Yesterday's Technology, and Tomorrow'sO

ur tour of the

Star Trek

computer has shown us an architecture that is already several decades old. The

Enterprise

computer in the original series is a 1960s computer blown up to gigantic speed and power. The computers of

The Next Generation, Voyager

, and

Deep Space Nine

are configurations from the 1970s and 1980s blown up to gigantic speed and power. None of these computers even reflect today's technical realities, much less what we expect tomorrow. Here are some aspects we expect will be quite different.

Sizeur tour of the

Star Trek

computer has shown us an architecture that is already several decades old. The

Enterprise

computer in the original series is a 1960s computer blown up to gigantic speed and power. The computers of

The Next Generation, Voyager

, and

Deep Space Nine

are configurations from the 1970s and 1980s blown up to gigantic speed and power. None of these computers even reflect today's technical realities, much less what we expect tomorrow. Here are some aspects we expect will be quite different.

Our computers are not getting bigger, they're shrinking. If you need to fix circuits in your PC, a wrench and a screwdriver won't get you very far. You can't fix your processor chip's circuitry with tools from your garage. The isolinear optical storage chip is too big, as well. Today's microprocessor chip is the size of a sugar packet. There's no way that a nanoprocessor chip of the future will be the size of a floppy disk.

Mainframe ConfigurationThere are still computer systems in use today that have configurations like the main computer of

Star Trek

. An old IBM mainframe or a VAX superminicomputer sitting in a cold room, with display terminals networked to it. But these are old systems. Far more prevalent are increasingly powerful PCs distributed around the globe and linked by the Internet. Everyone has local processing power. Nobody relies on a mainframe down at headquarters to prepare his monthly expense report.

Star Trek

computers have yet to reflect the technology of the 1990s.

Extremely Fast ProcessorsStar Trek

. An old IBM mainframe or a VAX superminicomputer sitting in a cold room, with display terminals networked to it. But these are old systems. Far more prevalent are increasingly powerful PCs distributed around the globe and linked by the Internet. Everyone has local processing power. Nobody relies on a mainframe down at headquarters to prepare his monthly expense report.

Star Trek

computers have yet to reflect the technology of the 1990s.

Processing speed today continues to escalate. In noting increasing processing speeds, as well as today's research into optical and holographic technology,

Star Trek

does acknowledge some real computer trends. Sadly, though, it pushes these trends into exaggerated and sometimes meaningless fantasy.

Centralized Storage and ProcessingStar Trek

does acknowledge some real computer trends. Sadly, though, it pushes these trends into exaggerated and sometimes meaningless fantasy.

Information today is distributed on PCs all over the world and linked by means of the Internet. The trend is clearly away from centralized data warehouses toward distributed information storage and processing. No computer today stores all information in the known universe. One of the marvels of the 1990s was Intel's supercomputer with 9,200 processors cranking 1.34 trillion operations per second. Still, such machines are uncommon to say the least.

Star Trek

reflects trends from an earlier time, the 1970s and 1980s.

Star Trek

reflects trends from an earlier time, the 1970s and 1980s.

What do we expect from real computers in the time of

Star Trek

? Remember, we're talking about computers in three to four hundred years. They'll be nothing like the computers of the 1960s, 70s, or 80s. Nor like anything we have today.

Star Trek

? Remember, we're talking about computers in three to four hundred years. They'll be nothing like the computers of the 1960s, 70s, or 80s. Nor like anything we have today.

Rather, they'll be invisible. They'll be in our walls, our air, our clothing, ourselves. Our bodies will merge flesh and computer technology. This is commonly called nanotechnology. Microscopic computers will dissolve our blood clots, heal our wounds, prolong our age, cure our diseases. Being artificially intelligent, the computers inside our bodies will retrieve information based on our changing interests and needs, draw conclusions for us, write and transmit our reports, help us become better artists, musicians, thinkers. These computers will repair themselves and will communicate with one another, just as computers communicate with each other today. Your body will contain a distributed processing network of microscopic computers. Your body network will communicate with mine.

Each computer will access information and routines stored in any computer anywhere in the known universe. A computer in your body network will obtain a symphony, play, book, personnel file of an employee, DNA patterns of your child, police records of a suspectâliterally anything that you're authorized to accessâfrom any computer anywhere. No more keyboards. No more voice recognition. Your DNA pattern or a combination of other unique biological stamps will serve as your password. You will think, “Where is Picard?” and your body network will find his body network, even if he's on another starship in a distant galaxy.

Around us, microscopic robots will fix the structures in which we live and play, mend our clothes, repair our equipment and roads, and manicure the grass. We'll live in a world of science fiction, except it'll be everyday stuff to us.

Given sensor capabilities, self maintenance and repair, and artificial intelligence, a real starship of the twenty-fourth century may come so close to being alive and sentient that the difference is more philosophical than practical (as in “Tin Man,” TNG).

Star Trek cannot show us what the future really will be like. If it tried to portray future computer technology more accurately, Trek would fail as a television program. The characters would sit and groan, and rarely move. The threats from aliens would be microscopic and thwarted before a character could part his lips. To be good televisionâwith action, adventure, and plotâTrek needs visual stimuli and entities, alien threats that are not so easily thwarted, and characters that run, scream, pull computer cables from the ceilings, and fix the ship with wrenches in the nick of time. But when we ask if Star Trek is an accurate depiction of what the future holds, we have to answer: Not even close.

3

Security

In the twenty-fourth century, hunger, disease, and poverty no longer exist within the Federation. Nor do racism or sexism or any other type of discrimination. Most people appear to be happy. Crimes of violence have been largely eliminated from daily life, leading to a more trusting and open society. Robbery and theft make little sense in a time of unlimited abundance.

A world without criminals needs little law enforcement. Which unfortunately suggests that the few illegal acts that do occur often go unpunished. For example, we note the following incidents from the original series:

⢠Kodos the Executioner, one-time planetary governor of Tarsus IV who responsible for the deaths of hundreds of civilians, remains at large under an assumed identity, that of the actor, Anton Karidian, for twenty years. (“The Conscience of the King,”

TOS

)

TOS

)

⢠Mr. Scott is accused of several brutal killings on the planet Argelius II. Though Scott's prosecutor knows way too much about the crimes, no one

suspects the officer of any wrongdoing. (“Wolf in the Fold,”

TOS

)

suspects the officer of any wrongdoing. (“Wolf in the Fold,”

TOS

)

⢠Captain Garth, a famous Federation Starfleet captain who has gone insane, seizes control of the penal colony on the planet Elba II. (“Whom Gods Destroy,”

TOS

)

TOS

)

⢠The Federation starship,

Aurora

, is stolen by scientist, Dr. Sevrin, and his followers, to hunt for a mythical planet they believe is Eden. (“The Way to Eden,” TOS)

Aurora

, is stolen by scientist, Dr. Sevrin, and his followers, to hunt for a mythical planet they believe is Eden. (“The Way to Eden,” TOS)

If we jump forward to the time of Picard, Sisko, and Janeway, there's no appreciable change in crime-fighting techniques or security measures. We note the following crimes, among many:

⢠An extragalactic intelligence gains control over important Starfleet officers. Only after a number of extremely unusual policy decisions and shifts in key personnel is the intruder detected. (“Conspiracy,”

TNG

)

TNG

)

⢠Crewman First Class Simon Tarses becomes a member of Starfleet (and gets to serve on the

Enterprise

) by falsifying his admission application to conceal that his grandfather is a Romulan. This information isn't discovered until Tarses is accused of sabotage during an investigation on the

Enterprise

. (“The Drumhead,”

TNG

)

Enterprise

) by falsifying his admission application to conceal that his grandfather is a Romulan. This information isn't discovered until Tarses is accused of sabotage during an investigation on the

Enterprise

. (“The Drumhead,”

TNG

)

⢠The Red Squad, a group of Starfleet cadets, sabotage Earth's power grid, with the blame for the incident falling on alien shapeshifters. Again, only through coincidence are the true culprits revealed (“Homefront,”

DS9

).

DS9

).

⢠Dr. Julian Bashir's parents, realizing their young son, Julian, is mentally handicapped, take him off-world to an illegal clinic where his DNA patterns are enhanced, greatly augmenting his intelligence and coordination. The operation is not discovered until years later, and only then through happenstance. (“Dr. Bashir, I Presume?”

DS9

)

DS9

)

Other books

The Sheriff's Sweetheart by Laurie Kingery

The Birds by Herschel Cozine

What We Find by Robyn Carr

The Case of the Murdered Muckraker by Carola Dunn

Snow Hunters: A Novel by Yoon, Paul

Cinders by Asha King

The Legend of the Rift by Peter Lerangis

Letters to Penthouse XXII by Penthouse International

Mr. Write (Sweetwater) by O'Neill, Lisa Clark

The Deptford Mice 1: The Dark Portal by Robin Jarvis