The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment (16 page)

Read The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment Online

Authors: Chris Martenson

Tags: #General, #Economic Conditions, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Development, #Forecasting, #Sustainable Development, #Economic Development, #Economic Forecasting - United States, #United States, #Sustainable Development - United States, #Economic Forecasting, #United States - Economic Conditions - 2009

What does it mean that debt has been accumulating in a nearly perfect exponential fashion? What will happen when it someday can’t continue to increase exponentially? What will change in terms of how the economy works and how stocks and bonds function as vehicles for storing and accumulating wealth?

We can begin to answer these questions by simply noting that debt has been growing faster than national income, and that such a system is unsustainable. Like any bubble, it will someday pop.

- Credit growth will peak, stall, and then decline, a process that I conclude began in 2008.

- The bubble will take somewhat less time to deflate than it took to inflate. If we date this to the start of the housing bubble in 1998, then we might expect it to bottom out somewhere around 2015, give or take. If instead we date the bubble to the early 1980s, then we might expect it to truly bottom out somewhere around 2025, +/− 4 years.

- Depending on where we date the start of the bubble (1998 or 1980 or even 1970), somewhere between $20 trillion and $30 trillion of debt in excess of income (GDP) has been piled up and will need to be eliminated in one fashion or another (i.e., by inflation or deflation). This will simply return debt back to the place from which it started, just the same as any other bubble.

Those predictions imply an immense amount of painful adjustment. If they come to pass, then the United States will be a vastly diminished nation in the twenty-teens and twenty-twenties as compared to 2008, with far fewer economic opportunities and less capacity to muscle through any other challenges that might arise.

By itself, exponentially growing credit isn’t necessarily a problem, but if it is growing faster than the economy, then it does become a problem.

We have a problem.

Withering Heights

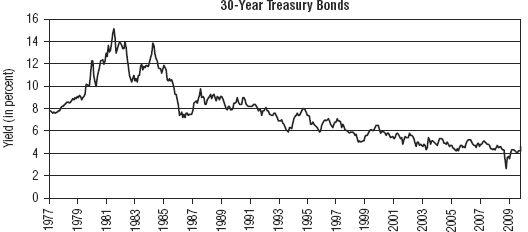

How was it possible to keep such a bubble going for so long? One essential factor was that interest rates constantly fell even as the total amount of credit market debt rose.

Here’s why this matters. Imagine that you had a credit card with a most unusual feature, whereby the rate of interest declined as the balance grew. The more you charged, the lower the interest rate became, which had the effect of stabilizing or even reducing the minimum payment due. Clearly such an arrangement would allow more borrowing than if the interest rates had not fallen (let alone risen). It is highly doubtful that the credit bubble would have developed without U.S. interest rates steadily falling over the 30 years between 1980 and 2010 (see

Figure 11.6

). This was really a perverse development when you think about it; interest rates should

rise

with a rising balance of debt, not

decline

. But there’s no law saying that these things have to make sense.

This practice of lowering interest rates to keep the game alive for awhile longer has a natural limit: Rates cannot go below zero. In 2010, we saw the Federal Reserve set interest rates for overnight money

2

to between zero percent and 0.25 percent, and we saw the interest rates on two-year Treasury notes go below 0.50 percent. There’s really nowhere else for them to go; they are already at zero. In short, interest rates hit bottom in 2010 and were placed there in an effort to keep the credit bubble expanding for a while longer. In my opinion this was an enormously misguided effort, but it happened, and now we need to consider how we’re going to manage the outcome(s) that will result.

All good things must come to an end, and if such low interest rates fail to keep the credit bubble on its “double every decade” trajectory, it is unclear what other remedies are available to the Fed that could cover the gap. The only ones I can think of are so “out-of-the-box” that how they might impact our future is impossible to determine. Some of these alternative measures might include complete Fed ownership of all productive assets (bought with thin-air money), a massive repudiation of all debt (just hit the reset button), and/or the Fed purchasing all government debt in an effort to keep things flowing, which has already partly been done with the first rounds of Quantitative Easing (QE).

The alternative would be to admit to ourselves that perhaps doubling debt every decade (far faster than income growth) isn’t a sustainable practice and willingly terminate our efforts to continue on that path. If we do, then the economy will have to grow well below its potential for a period, to offset the time when the steroid injections of debt unnaturally swelled its growth.

The Austrian school of economics has a very crisp and historically accurate definition of how a credit bubble ends. According to Ludwig von Mises:

There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as a result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.

10

In plain language, either we willingly end our efforts to continue doubling our debt faster than income, or we risk seeing the dollar collapse. While growing a bit slower than the hectic pace to which we have become accustomed will be

slightly

painful, a currency collapse would be

enormously

painful, not just to the United States but to the world. As a nation, the United States has undertaken desperate measures to avoid abandoning the continuation of its credit expansion, leaving a final catastrophe of its currency as the most likely outcome.

As for the timing? It could hardly be worse. Dealing with a bursting credit bubble is hardly the sort of challenge we need at this particular moment in history, where energy and environmental issues loom large. But here we are. The stewardship and vision displayed by the Federal Reserve and Washington, DC, in shepherding us to this position leaves a lot to be desired.

So, what can we expect from a collapsing credit bubble? Simply put, everything that fed upon and grew as a consequence of too much easy credit will collapse back to its baseline position. Where we lived beyond our means for too long, we will have to live below our means until the excesses are worked off. Living standards will fall, debts will default, and times will be hard. Those are the lessons of history.

But there’s more to this story than the simple accumulation of debt, even as serious as that is all by itself. We’ll explore more of the story later when we discuss the role of energy in supporting economic growth. For now, let’s just hold onto the idea that in order for the next 20 years to resemble the past 20 years, total debt will have to double and then double again. How likely does that seem to you?

1

Mathematicians and other scientists have a means of assessing how accurately an observed event conforms to, and therefore can be explained and even predicted by, a mathematical formula. For example, if you saw the number series 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, you would instinctively predict that the next number in the series would be 7. The way a mathematician would approach this would be to arrive at the number seven by converting the number series into a formula, y = × + 1, and then testing this formula against the number series using a statistical method that calculates the variance between observed and predicted results.

The term for this method is “goodness of fit,” which means just what it sounds like: How close of a fit was there between the measured variables and one’s formula? In this example, the formula perfectly matches the observed number series and because it does, it is said to have a perfect “fit,” which means it is assigned a value of “1.” An utter lack of “fit” would be assigned the value of “zero.” By convention, a perfect fit, as in our number example above, is said to have a value of 1.0, while a formula with a no descriptive or predictive power at all would have a “fit” of zero. In my science days investigating messy, real-world biological systems, a fit of 0.80 or better was a very good fit, meaning that a real and predictable (and therefore understandable) process was being studied and the scientists involved would get excited like hounds on a strong scent. But a “fit” of 0.90 or better? Practically unheard of for the systems I studied. Experimental noise and biological complexity conspired against such robust readings.

Now let’s imagine another system designed and run by biological creatures with enormous, nonlinear complexity built into it, which we seek to similarly describe and understand by “fitting” it with a mathematical formula. I’m speaking of a system composed of millions of moving parts arising from billions of individual decisions and totaling in the trillions of dollars. The entire system is in constant flux, with many of the parts interacting with each other in a delicate, chaotic symphony of positive and negative feedback loops. From a ground-up perspective, such a massive and complicated bit of machinery would seem to defy easy characterization and offer slim hopes for getting a good “fit.” The system I am speaking of is the entire, massive, complex credit market of the United States (although other countries would work equally well in this example), which is composed of every manner of type of debt you can imagine, spanning multiple decades with wars, recessions, booms, and bubbles interspersed along the way. Mortgages, derivatives, federal debt, auto loans, municipal debt, student loans, and dozens of other types of debt are all mashed into one, gigantic market. What’s your prediction for how well we can describe the growth in this market over the past 50 years? How good will our “fit” be? Will it be a horrid 0.50 or less, a respectable 0.65, or perhaps something higher? The answer surprised me enormously when I performed the test; our total credit markets are described by an exponential function with a “fit” of 0.9937 (!!). That’s as close to perfect as you can get without actually being perfect. It is powerful evidence that our credit markets operate exponentially.

2

Overnight money is also known as the Federal Funds Rate. When you read about the Federal Reserve raising or lowering the interest rate, it is this rate to which they are referring.

CHAPTER 12

Like a Moth to Flame

Our Destructive Tendency to Print

The twenty-teens will be marked by the collapse of sovereign debt. When the Great Credit Bubble first began to lurch about unsteadily in 2008 as the consumer withdrew, most governments of developed nations predictably turned to Keynesian stimulus to try and keep the bubble going. What this means is that they racked up enormous and unprecedented levels of debt trying to stabilize the situation, and this debt will someday need to be paid back.

History is quite clear on the subject: Whenever governments or countries have found themselves saturated with too much debt totaling more than could possibly be paid back out of their productive economy, they’ve nearly always resorted to money printing. As mentioned earlier, in times past this meant physically debasing the coinage of the realm by reducing the purity of the silver or gold in the coins, or by making the coins smaller, or both.

Moths

In the fourth century bc, Dionysius of Syracuse became the first recorded ruler to debase his currency in order to pay down his accumulated debt. In the more recent past, this has meant running actual, physical printing presses and churning out wheelbarrow loads of paper cash, as Germany did in the 1920s and Zimbabwe did in the 2000s.

Today “money printing” means using computers to generate electronic entries denoting money. The difference between then and now is that today’s debasements are virtually instantaneous and are not as easily observed by the common person. Where it took several decades for the Roman Empire to debase its coinage (contributing to its downfall), it only took Germany about five years to accomplish the same task in the 1920s using paper printing presses. Today it’s possible to create unlimited quantities of money almost instantly with just a few strokes on a keyboard.

Despite these “advances,” the core of the matter has not changed one bit over the centuries. In all instances, additional money is created without the benefit of anything else being produced. Once we understand that money is a claim on wealth, but not wealth itself, it becomes obvious why simply printing more of it neither creates wealth nor corrects the problem of having previously consumed more than one has produced. Money is not wealth; therefore printing it does not create wealth or solve the problems of the past that arose due to printing too much money.

The purpose of this chapter isn’t to present an exhaustive recounting of economic history, although there are many fascinating tales to be told, but to help us assess what the future might hold. In order to mitigate our economic risks, we have to know what they are.

Which path or outcome is most likely? Will we head down a path of inflation or deflation? Should I hold cash, gold, land, stocks, bonds, or something else?

Flames

Recall from Chapter 10 (

Debt

) that there are only three ways for a government to get rid of its debt:

1. Pay it off.

2. Default on it.

3. Print money.

If we put ourselves in the shoes of the leaders who choose money printing, it’s easy to understand why that option is nearly always selected over the other two, both of which are dreary and difficult options.

Because debt is a claim on the productive output of a country, the first option, paying off the debt, is deeply painful because it bleeds off economic growth and directs the nation’s productive output into the hands of creditors. In practical terms, “paying off debt” means that the government has to tax its citizens so that it can hand that money over to the debt holders. It means higher unemployment, fewer goods and services, and therefore a restive and unhappy citizenry. Throughout all of history, raising taxes has always been a deeply unpopular move, but even more so if the collected taxes are siphoned away and don’t result in any additional benefit to the citizens in the form of an obvious expansion of government services or perhaps a redistribution of wealth within that government’s borders.

There are, however, precious few historical examples of governments choosing this option. After the Napoleonic wars, England found itself deeply in debt and chose to put itself through a crushing round of deflation, opting not to default or inflate away its debt. Despite hitting a record of 260 percent debt-to-GDP, England managed to pay its debt down to a quite manageable level of less than 50 percent of GDP by the turn of the twentieth century. However, several conditions were in place that allowed this course of action to be chosen.

First, most of the debt was internally financed, as the ruling class, who were well represented in Parliament, held most of it. As they put the rest of the country through a serious deflationary event, the value of their own bonds surged in relative value. In essence, they voted to give themselves a rather large transfer of wealth, which was a strong motivator. Second, the English economy was just entering the Industrial Revolution, one of the most explosive periods of economic growth and wealth creation in history. Large debts can sometimes be serviced through the miracle of rapid economic growth, and that proved true in this case. Third, most of the debt was accumulated in the form of war expenditures, which were easily and rapidly curtailed once the hostilities were over. In other words, the debt wasn’t due to structural deficits, as is the case for many developed nations today that face daunting pension and entitlement expenditures in which the ongoing demands are quite different from those of a war that ends.

The second option, default, is a horrible political option for two reasons. First, defaulting on the external portion of a country’s debt is a sure way to render that country an international pariah. Nobody will trade with it, except on a cash-only basis, which is very difficult to do if your currency is collapsing (a typical consequence of a debt default). The economy of the country will suffer through the loss of needed goods, and the citizens will be deeply unhappy.

For example, imagine what would happen to the United States, which imports two-thirds of its daily petroleum needs, if it defaulted on its external debt. If even a few of its exporters decided they would no longer accept U.S. dollars in exchange for their oil, the dollar would quite rapidly lose its international value, oil priced in U.S. dollars would spike enormously, and the U.S. economy would be immediately and quite possibly permanently damaged. This means that “external default” wouldn’t generally be a viable strategy even if the political will for this option did happen to exist.

To the extent that debt can be defaulted upon internally, it’s also typically an unworkable option because the holders of that debt, as we saw in the England example above, are almost invariably wealthy and well-connected individuals with excellent opportunities to influence the decisions of government. Very rarely do people vote to impose massive losses on themselves, so internal defaults are also extremely rare.

This leaves the third option, money printing (or its electronic equivalent), as the most viable of the three options and explains why it’s almost always the preferred choice. The irony here is that it’s also the most dangerous path to take, but because its destructive effects are lodged in the future somewhere, it pushes the day of reckoning to a later time (when it could very well be somebody else’s problem anyway) and even offers a sliver of hope, however false.

Hey, it just might work this time! This time might be different!

Alan Greenspan made a number of crucial errors during his tenure as chairman of the Federal Reserve, but before he held that position, he wrote this remarkably lucid and correct assessment of gold and its role in helping to shield people from the effects of governmental money printing (written in 1966, when he was managing the consulting firm Townsend-Greenspan & Co. in New York).

In the absence of the gold standard, there is no way to protect savings from confiscation through inflation. There is no safe store of value. If there were, the government would have to make its holding illegal, as was done in the case of gold. If everyone decided, for example, to convert all his bank deposits to silver or copper or any other good, and thereafter declined to accept checks as payment for goods, bank deposits would lose their purchasing power and government-created bank credit would be worthless as a claim on goods. The financial policy of the welfare state requires that there be no way for the owners of wealth to protect themselves. This is the shabby secret of the welfare statists’ tirades against gold. Deficit spending is simply a scheme for the confiscation of wealth. Gold stands in the way of this insidious process. It stands as a protector of property rights. If one grasps this, one has no difficulty in understanding the statists’ antagonism toward the gold standard.

1

Inflation has the effect of reducing the real value of public debts; it makes them smaller by making the money in which they’re denominated worth less. Inflating debt away represents a stealthy form of default, but one which avoids a declaration of a formal breach of contract. Of course, to inflate away debt, the government must have control of the printing press, something impossible in the individual Eurozone countries that are united under the single currency of the euro.

Historically, defaulting nations have typically either been the financially weaker developing countries or nations that have proven to be credit risks in the past. Between 1800 and 2008, there have been 250 cases of external bond defaults and only 68 cases of internal default.

2

So defaults have happened in the past, but in today’s globalized economy, food and energy security often lie outside a nation’s borders, greatly complicating the situation.

Today there are a number of countries that could not possibly support their populations without a steady supply of imports, which changes the dynamic considerably. For these reasons and a number of others, the safest bet is on printing, with defaults and “paying it back” taking (very) distant second and third positions, respectively.

To draw once again from Rogoff and Reinhart’s remarkable 800-year romp through history, we can observe periodic episodes of sovereign defaults against an almost constant backdrop of inflation. What is stunning is that every country in both Asia and Europe experienced an extended period of history with inflation over 20 percent between the years 1500 and 1800, and most experienced a significant number of years with inflation over 40 percent. However, deflations tended to follow each inflationary episode, so after all the ups and downs, prices tended to center around the same levels over the centuries.

In the period from 1800 to 2006, Rogoff and Reinhart note that inflation was ever more frequent and attained higher levels, thanks to the ease offered by modern printing presses. Prior to 1900, their data shows that the world cycled between inflation and deflation on very short cycles of around 10 years, again keeping price levels roughly in check around a median value. But since the last deflationary episode in the 1930s, the world spent the next 80 years in one long, sustained inflationary episode, with no downdrafts to moderate prices.

It is also true that since the 1930s, oil has yielded nearly all of its energy bonanza to humanity, and only in 1971 did fiat money lose its final tether to the firmament of earth when President Nixon cut the dollar’s tie to gold.

1

These aren’t unrelated events. The particular style of debt-based money on which we operate requires the very sort of continuous expansion that petroleum offers, while spending massively beyond one’s means requires that no physical, tangible anchor exist to limit the spree. This means that

this time it

really

is different

, because the story now involves so much more than a relatively simple case of too much debt being held by a single country. This time the entire globe is involved and there are critical resource issues involved. Most of the world is now chained to and operating on a debt-based monetary system that requires perpetual exponential growth to operate. But that’s the big-picture conclusion; for now it serves our purposes to simply note that the safest bet is to predict that monetary printing, or its modern equivalent, lies in our collective future.

Quantitative Easing

The prediction I began making in 2004 was that we’d enter a period of profound money printing by the Fed in order to try and “fix” things. Given the fact that the Federal Reserve and other central banks in Europe and Japan began an aggressive monetary printing program in 2008 that has continued through the time of this writing (2010), this “prediction” is now an observation. The printing has already started in earnest. These money-printing programs go by the fancy name of quantitative easing (QE), which simply refers to creating money out of thin air and then using it to buy various forms of debt, both governmental and nongovernmental. Between 2008 and 2010, the Fed’s balance sheet expanded from $800 billion to just over $2,250 billion, all of which represents money created out of thin air for the purpose of monetizing existing debt (

Figure 12.1

).