The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment (19 page)

Read The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment Online

Authors: Chris Martenson

Tags: #General, #Economic Conditions, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Development, #Forecasting, #Sustainable Development, #Economic Development, #Economic Forecasting - United States, #United States, #Sustainable Development - United States, #Economic Forecasting, #United States - Economic Conditions - 2009

And All the Rest

Statistical wizardry similar to that which we’ve explored here for GDP and the CPI is also performed on income, unemployment figures, house prices, budget deficits, and virtually every other government-supplied economic statistic that you can think of. Each is saddled with a long list of lopsided imperfections that inevitably paint a rosier picture than is warranted. Taken all together, I call the economic stories that we’re handed by government statisticians “Fuzzy Numbers.” To quote Kevin Phillips again: “. . . our nation may truly regret losing sight of history, risk and common sense.”

14

CHAPTER 14

Starting the Race with Our Shoes Tied Together

In the spring of 2001, while returning from a trip to Europe, I was in the back of a taxi heading home from JFK airport outside of New York City on an important phone call, trying to negotiate a contract with a new client. “What?” I asked, “I couldn’t make that out . . .” as my phone connection went fuzzy. Just then, the taxi hit an enormous pothole, its third in as many minutes, and I lost the phone connection. Physics tells me these were unrelated events, but they felt connected. Redialing, embarrassed, and apologizing for the lost connection, I was struck by the thought that I had not had a single dropped call while in Europe, not when traveling through the 26-mile long Chunnel on a train beneath hundreds of feet of rock and water, not even in elevators. While stewing over the lost phone call and the rough ride from the airport, it struck me just how shabby and decrepit much of the U.S. physical infrastructure had become. As I recall, the business deal turned out okay, but instances such as these surrounded some of my first budding doubts about the health of our country.

In a 2005 report, the American Society of Civil Engineers assessed the condition of 12 categories of infrastructure, including bridges, roadways, drinking water systems, and wastewater treatment plants. They gave the United States an overall grade of “D” and calculated that $1.6 trillion would be needed over the next five years to bring the United States back up to First World standards.

1

At the time of this writing in 2010, almost none of these investments have happened. Because inflation has advanced since then and more deterioration has occurred, the bill has certainly grown. “Clean, modern, and efficient” no longer describes the United States in 2010; those days have passed. The United States can get there again, but it will take an enormous fiscal commitment to enjoy First World infrastructure once again.

Choices matter, and the United States has repetitively chosen to defer maintenance and upgrades on essential economic infrastructure until some future date. There’s a long story there, but for now, we can simply note that one of the many demands on the United States’ limited pool of future funds will be the required investment in, and repair of, its physical infrastructure.

A National Failure to Save

Even if the United States were about to embark on another 1990s-style economic boom on a par with the Internet revolution, it would still face structural headwinds that will place enormous demands on future funds. Unfortunately, no such savior technology is readily apparent at this time. Given the sheer number of economic currents and other financial demands that lurk in the near future, it would be ideal if the United States were entering the twenty-teens with high levels of rainy-day funds socked away. But this isn’t the case.

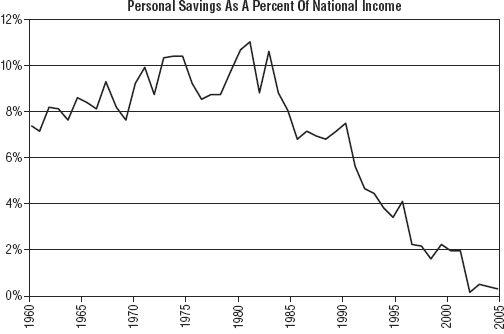

In 2007, it was reported that the personal savings rate had plunged to historic lows, levels last seen during the Great Depression when people were dipping into savings to buy food and pay the rent. This created the false impression that the modern savings rate was a result of a sudden crisis.

2

In fact, the personal savings rate had been steadily declining since around 1985 (see

Figure 14.1

), indicating that this failure to save wasn’t just a recent notable blip on the economic radar, but rather the culmination of a multidecade process.

Figure 14.1

Personal Savings Rate from 1960 to 2010

The personal savings rate is the difference between income and expenditures for all U.S. citizens expressed as a percentage.

Source:

Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Note that the long-term historical average for U.S. citizens between 1960 and 1985 was 9.2 percent. For comparison, in Europe in 2009 that number was just over 15 percent,

3

and between 1978 and 2000 China’s national saving rate was a stunning 37 percent of its GNP.

4

Savings are important to us individually because they form a cash cushion that can get us through economically difficult times. They are also important at the national level, because a nation that doesn’t save is a nation that steadily grows poorer. Savings contribute to investments in property, plant, and equipment that lead to the formation of future wealth.

However,

Figure 14.1

somewhat obscures the fact that the extremely wealthy raked in most of the income gains during the 1990s and 2000s, which allowed them to save enormous amounts of money, while the lower socioeconomic brackets suffered income declines and posted savings rates that were deeply negative. It all averages out to one low rate of savings, but that’s like having one foot on hot coals and the other in a bucket of ice water and saying that, on average, your feet are at a comfortable temperature. One group saved a lot because they could, and the rest couldn’t save at all. Why is this important? Because, as the Greek philosopher Plutarch once observed, “An imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics.”

5

One possible explanation for the declining savings rate is the rise in the use of credit seen over the same period of time. Where a savings account once provided a buffer to life’s vicissitudes, the idea now is that credit cards and home equity lines of credit (HELOCs) can perform that task without the bother of foregoing any of life’s pleasures while building up savings. In what qualifies as a case of cultural whiplash, in only 25 short years the United States entirely replaced a “save and spend” mentality with a “buy now, pay later” approach. Lending credence to this overall idea is the observation that the savings rate began its decline right around 1985, coinciding perfectly with our long, steady rise in debt accumulation. Savings and cash cushions were swapped for debt and credit lines.

Another type of saving exists in the form of pension and retirement funds. State and municipal pensions are in horrible shape, and in 2010 were found to be underfunded by $3 trillion and more than $500 billion, respectively.

6

This happened for two reasons. First, various governmental administrations regularly made the decision to defer funding of these promises until some later date. This had the double effect of preserving more money for current spending while also keeping taxes down—two irresistible goals of any town, city, or state administration. Second, the plan administrators were allowed to make absurd projections of future rates of return, sometimes as high as 11 percent per year. These were clearly not achievable, yet the assumptions remained in place. The attractiveness of this practice is that the higher the assumed rate of return, the less money had to be placed into the account.

For example, if a town’s pension administrators knew that they’d need $100,000 in 10 years to pay off a pension obligation, their assumption of an 11 percent rate of return would only require them to place approximately $35,000 into the pension fund. If instead they assumed a much more modest and achievable return of 5 percent, which averages out the good years and the bad, they would be required to put roughly $61,000 into the fund, or 95 percent more. This is why plan administrators have often made wildly unrealistic assumptions about plan returns. Once again, the miracle of exponential growth has crept into a story, this time with seemingly minor assumptions about percentages compounding into very substantial predicaments, and once again exponentials are proving to be a substantial foe.

The problem with using such wrong assumptions is that instead of working for you, compounding works against you. Even a slight miss in returns a few years back will mushroom into a very large future shortfall. That’s just how compounding works, and that’s exactly where hundreds of underfunded pension plans now find themselves.

To illustrate how this will play out, consider the case of Vallejo, California, where mandatory pension payments, long-deferred but finally unavoidable, ate into the current budget too deeply to avoid cutting other current services. Faced with unmovable public employee unions, escalating pension costs, and a rapidly shrinking budget, the city was forced to declare bankruptcy in 2008.

7

By 2010, the city had slashed its police force from 160 to 100, requested that its citizens use the 911 system as little as possible, and cut funding to youth groups, a senior center, and arts organizations. In other words, past promises have caught up with current spending. For the leaders of Vallejo, the future they hoped would never come has arrived. This critical tension between pension promises that were far too generous to ever be supported (even under a regime of healthy economic growth) and the need to direct municipal and state revenues to current services is sure to dominate the financial landscape of the twenty-teens.

What does it mean when we say that the state and municipal pensions are underfunded by a trillion dollars? How is that calculated? The trillion-dollar shortfall is what is called a Net Present Value (NPV) amount. An NPV calculation adds up all the cash inflows and offsets (or “nets”) those inflows against all the future cash outflows. Since a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in the future, the future cash flows have to be discounted and brought back to the present. We net all the cash inflows and costs, and discount them back to the present to determine if the thing we’re measuring has a positive or negative value.

This is the methodology used to calculate the status of state and municipal pension funds. Growth in the value of the pension fund assets plus future taxes are offset against cash outlays to pensioners, brought back to the present to indicate that in order for the pension funds to have zero value (in other words, to avoid having negative value or being “in the hole”), $1 trillion would have to be placed in those funds

today

.

1

In 2008, corporations, coming off one of the highest levels of profitability in history, had similarly underfunded pension obligations amounting to over $400 billion (again, in NPV dollars).

8

But it’s only when we get to the U.S. federal government entitlement programs that the truly scary numbers emerge. Lawrence Kotlikoff (a Boston University economics professor) has studied the issue as closely as anyone and calculated in 2010 that the U.S. federal obligations are underfunded by $202 trillion, or more than 8 times current GDP.

9

He glumly concluded that the U.S. government has been effectively running a Ponzi scheme and that highly unfavorable math will severely crimp future prosperity:

And [the Ponzi scheme] will stop in a very nasty manner. The first possibility is massive benefit cuts visited on the baby boomers in retirement. The second is astronomical tax increases that leave the young with little incentive to work and save. And the third is the government simply printing vast quantities of money to cover its bills.

Most likely we will see a combination of all three responses with dramatic increases in poverty, tax, interest rates and consumer prices. This is an awful, downhill road to follow, but it’s the one we are on.

10

Two things are perfectly clear: There will be less money to go around in the future, and standards of living will fall as a result.

In case you’re harboring the notion that there’s some money socked away in a special U.S. government account, like in some kind of lockbox, I regret to inform you that there’s no “trust fund.” All of the excess Social Security receipts collected over the years have already been spent. The “trust fund,” such as it is, consists of several three-ring binders, locked in a filing cabinet in an otherwise-unremarkable government building in Virginia, which are filled with slips of paper representing IOUs from the government to itself.

Some people are confused by the fact that these IOUs are known as “special Treasury bonds” that promise to pay the funds back when needed in the future, with interest. That certainly sounds official and trustworthy. But the problem is, it’s not possible for the government to owe itself money, especially money upon which it has promised to pay interest. It’s not possible for

any

entity to owe itself money; by definition there cannot be any value in a promissory note issued by an entity from itself to itself. It would be an accounting fiction to suggest otherwise, and in private industry this practice is considered fraud (e.g., Enron).