The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment (33 page)

Read The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment Online

Authors: Chris Martenson

Tags: #General, #Economic Conditions, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Development, #Forecasting, #Sustainable Development, #Economic Development, #Economic Forecasting - United States, #United States, #Sustainable Development - United States, #Economic Forecasting, #United States - Economic Conditions - 2009

We’re already at the point where water is a limiting factor for societies and economies all across the globe. With 6.5 billion souls (and counting) living the way we do, all the fresh water on the face of the earth, and even that beneath the surface, is barely meeting our needs. What happens when the world’s population goes to 9.0 billion, as the UN suggests is likely by 2050? At a simple level, this nearly 40 percent increase in population implies that there will be 40 percent less water per capita in the future. More realistically, we might wonder if the number will be a lot larger due to the permanent loss of several or more ancient aquifers.

The future of water is one of scarcity. It’s a future where “water refugees” will need to move from regions where the local aquifers can no longer support the populations above them, and where nations will squabble and possibly go to war over water rights and access. It’s hard to imagine how this water scarcity won’t translate into crop and food scarcity.

Water use provides a perfect illustration of the gap between the “grow now at any cost” mentality and a rational, thoughtful approach. If a city is drawing upon a depleting ancient aquifer, has no other plans for water, and continues to grow, then it’s being led by people who are either deeply irrational or who lack an appropriate horizon of concern.

Unfortunately, this description applies to many cities all over the world, including many in so-called developed nations. The evidence is dramatic and overwhelming, and it’s time for us to come to terms with it. The alternative is to wait for circumstances to force the issue, risking prosperity and even water wars.

CHAPTER 22

All Fished Out

I loved fishing with my grandfather when I was a child. I can’t recall us ever talking about anything—not one conversation comes to mind—but there was no need for words; we were

fishing

. He took me to the Branford public pier on the Long Island Sound, and we caught many different types of fish there. The waters were teeming with life. I remember an abundance that, sadly, is no longer in evidence there when I take my kids fishing.

Once again, this chapter isn’t designed to be a long recitation of the many challenges that our oceans are facing—there are too many to list—but I’ll continue to make the simple point that we’re already up against hard limits with respect to what the oceans can provide. More growth? Another 10, 20, or 30 years of increasing exploitation of the ocean’s riches? It’s not going to happen. They’re already fished out.

Ninety Percent Gone

A recent study published in the esteemed journal

Nature

concluded that the combined weight of all oceanic large fish species has declined by 90 percent.

1

If something supposedly renewable is being harvested at a rate that causes its mass to shrink alarmingly, then it’s a poster child for the concept of “unsustainability.”

As Lester Brown put it in Plan B 3.0:

After World War II, accelerating population growth and steadily rising incomes drove the demand for seafood upward at a record pace. At the same time, advances in fishing technologies, including huge refrigerated processing ships that enabled trawlers to exploit distant oceans, enabled fishers to respond to the growing world demand. In response, the oceanic fish catch climbed from 19 million tons in 1950 to its historic high of 93 million tons in 1997. This fivefold growth—more than double that of population during this period—raised the wild seafood supply per person worldwide from 7 kilograms in 1950 to a peak of 17 kilograms in 1988. Since then, it has fallen to 14 kilograms.

2

As population grows and as modern food-marketing systems give more people access to these products, seafood consumption is growing. Indeed, the human appetite for seafood is outgrowing the sustainable yield of oceanic fisheries. Today, 75 percent of fisheries are being fished at or beyond their sustainable capacity. As a result, many are in decline and some have collapsed.

Cod, bluefin tuna, swordfish, shark, herring, and innumerable other species are in rapid decline and are in danger of collapsing or becoming extinct. This isn’t some future issue that we might worry about; it’s happening right now.

While overfishing puts serious pressure on oceanic health, probably the worst problem of the lot right now, there are other problems as well, ranging from destruction of estuaries, loss of coral reefs, oceanic “dead zones” caused by pollution runoff, and the build-up of toxic metals and other industrial pollutants in the top species.

Sperm whales feeding even in the most remote reaches of Earth’s oceans have built up stunningly high levels of toxic and heavy metals. [R]esearchers found mercury as high as 16 parts per million in the whales. Fish high in mercury such as shark and swordfish—the types health experts warn children and pregnant women to avoid—typically have levels of about 1 part per million.

3

What sort of signal should we receive from the fact that whales—mammals just like us—now carry toxic loads of mercury so far beyond what the EPA would allow in humans that they would probably require a person so infused with mercury to be buried in a special leakproof casket to prevent the release of hazardous materials?

The Air You Breathe

I was taught in middle school that the oxygen I breathe comes from trees. That’s not entirely wrong; it’s just not entirely accurate either. The source of half the world’s oxygen is not majestic trees in the Amazon rising hundreds of feet into the mist, but microscopically invisible one-celled creatures that live at the ocean surface, tossed hither and yon by majestic waves and currents.

4

Called “phytoplankton,” which is a fancy way of saying “photosynthetic organisms that are really small and live in the ocean,” these little “trees of the ocean” are responsible for far more than half the oxygen you breathe; they are the very base of the food pyramid in the ocean.

On land, plants form the base of the pyramid, and these plants are eaten (for example) by the rabbits that are eaten by the foxes. In the ocean, phytoplankton are the plants, which are eaten by slightly larger plankton and larvae, which are eaten by . . . well, you get the picture. There’s an entire ecosystem and food chain in the ocean which exactly mirrors the one on land in its basic pyramid shape, but it is eons older in terms of its layers, complexity, and structure. Life started in the sea and has a billion or more years of a head start on terrestrial life when it comes to complexity (e.g., interrelationships, dependencies, feedback loops, and the like).

This is all well and good and perfectly ignorable until we read things like this:

The microscopic plants that support all life in the oceans are dying off at a dramatic rate, according to a study that has documented for the first time a disturbing and unprecedented change at the base of the marine food web.

Scientists have discovered that the phytoplankton of the oceans has declined by about 40 per cent over the past century, with much of the loss occurring since the 1950s.

5

While we don’t know if this finding will hold up, or what might be causing it if it is real, it’s a trend that has been tracked by scientists for quite a long time.

6

,

7

If such findings are true, we should be just as focused on why half of the world’s supply of oxygen is disappearing as why our GDP is not growing as rapidly as we might like.

The very air you breathe is dependent on a form of life that you almost certainly have never seen with your own eyes, and something seems to be amiss with it. Whether the cause is global warming, nutrient imbalances, or an upset in the normal predator-prey relationships is utterly unknown at this point. Wouldn’t it be good to know what the cause is? Without (hopefully) belaboring the obvious, human pressures on the oceans, in whatever form, are a ripe candidate for speculation and inquiry.

The Bottom Line

All of the data coming from the oceans says that even at a population of 6.5 billion, humans are exerting unsustainable pressures and demands upon the world’s oceans. There is much we don’t understand about our saltwater resources, probably because, like aquifers, they are out of our direct sight and therefore our appreciation.

But one thing that we can be sure about is that, by definition, unsustainable practices must someday stop.

As we head toward 9.5 billion people, what are the chances that we’ll be able to wrest 40 percent more fish from the oceans?

The answer is somewhere between zero and none.

We’re already at limit, and probably beyond, when it comes to the oceans. The story of perpetual economic growth, then, will have to be told without getting more resources from the oceans. They are all tapped out and headed toward collapse, with reductions in certain key areas and species upon which we already depend for much of our protein.

For any who care to look, signs are present that we have either hit or are rapidly approaching hard, physical limits all around us. This isn’t a case of pessimism; this is simply what the data is telling us at this time. Whether or not you choose to heed the warning signs and adjust your life to the implications of this information is for you to decide.

In my own lifetime, a mere blink by historical human standards, I’ve personally witnessed what seems like the complete demise of shore-based fisheries. In many places, there’s nothing left to catch. The water is beautiful on the surface, but underneath it’s a desert. Our oceans are rapidly growing devoid of all the larger forms of life, and now, as we’re finding out, this sad fact extends to even the microscopic ones as well. When I consider just how rapid this depletion of the ocean’s resources has been, I think back to our stadium example—as far as the oceans are concerned, the water is already swirling up the staircase to the bleachers.

PART VI

Convergence

CHAPTER 23

Convergence

Why the Twenty-Teens Will Be Difficult

The next 20 years are going to be completely unlike the last 20 years. Perhaps this sounds trite, in the sense that change accompanies every decade, but I mean to convey something more profound, and possibly more disruptive, than the usual pace of change that we’ve seen in the past. A trait that all humans share is that we extrapolate from the past into the future. Whatever just happened becomes our model for what is most likely to happen next. If the surly store clerk has treated us poorly six times, we will expect the clerk to respond similarly on the seventh. If we slip on ice outside our front door twice, we’re more careful the third time we step out. But in the case of the past 20 years, in which we’ve learned that economies grow, technology improves, and the cure to bursting bubbles is cheap money, it’s most likely that these lessons will prove to be more misleading than helpful.

If I’m right (or more accurately, if the data in the prior chapters has been correctly assembled and interpreted), then we’re on the cusp of major change—the kind where the amount of time and resources we dedicate to mitigating the risks will prove to be the best investment we could ever make. As someone who has done a lot of recreational rock climbing and some over-the-horizon boating, I have a strong appreciation for the difference between “sort-of” prepared and actually prepared. When you’re 600 feet up a rock wall, either you have a critical piece of gear or clothing with you, or you don’t. Trust me, being stuck that high up without rain gear because it was too nice at the bottom to justify hauling it up can result in a very memorable experience. Once you’re out of sight of land, if you get into boating trouble, you either have an emergency locator beacon with you—or you don’t. If you do, the rescue crews can find you instantly; if not, they may never even know you’re in trouble, let alone where to look once you’ve been reported missing.

It is my central belief that our future contains exceptionally high risks that could usher in political and social unrest, a collapsing dollar (and other fiat currencies), hyperinflation (or hyperdeflation), and even full economic collapse. But it’s important that you understand that these are merely risks, not certainties. My background as a pathologist trained me to view the world as a collection of statistics and probabilities; nothing is ever black and white to people in my (former) profession. People who smoke four packs a day are at higher risk of certain diseases, but are not certain to die of anything in particular. Cancer exists on a continuum of aggressiveness, which we segment into stages, but even then, there are no guarantees as to the outcome of an individual case. Similarly, when I look into the future, I don’t have any certainty about what might come next; instead, I see risks to be weighed and mitigated.

It’s also important to note that I don’t get rattled easily. I undertook no preparations for Y2K, and I don’t fret about flying or driving or being near secondhand smoke. I rock climb and shoot and eat meat. To me, everything is a series of risks, some large and some small, with relatively few above my personal threshold of attention and most below.

The risk that I’m most focused on isn’t any particular one of the individual predicaments laid out in the previous chapters. Rather, I’m primarily concerned about the general

possibility

that two or more may converge on a very narrow window of the future in a fashion that could overwhelm the ability of our systems and institutions to adapt and respond. Like a rogue wave formed of lesser parts, two relatively small issues could join forces and prove to be far more destructive and disruptive in combination than individually. Let’s review the key elements now in order to better appreciate the risks.

The Foundation

Exponential growth defines the human experience of the past few hundred years. With the advent of effective medicine and abundant energy, exponential population growth became so embedded in our collective reality that we designed both monetary and economic systems around its presence. Without such robust economic growth, as was the case in 2009 when global GDP shrank by a mere 2 percent, our banking system practically collapsed and was said to have been only hours away from meltdown.

1

All growth requires energy, and if there happens to be abundant surplus, both growth

and

prosperity can result. However, if there is insufficient surplus to “fund” both, then you can only enjoy one or the other. If this comes to pass, it will not be a problem to solve, but a predicament to manage.

The Economy

To review, our understanding of the economy began with the fact that money is loaned into existence, with interest, and that this results in powerful pressures to keep the amount of credit, or money, constantly growing by some percentage each year. This is the very definition of exponential growth, and money and debt have been growing exponentially (very nearly perfectly) for several decades.

Keeping this dynamic in mind, we dove into the data on debt, which is really a claim on the future, and saw that current levels of debt vastly exceed all historical benchmarks. The flip side to this (a significant sociological trend in its own right) is the steady erosion of savings that has been observed over the exact same period of time. Combined, we have the highest levels of debt ever recorded, coincident with some of the lowest levels of savings ever recorded. We also saw that our failure to save extends through all levels of our society and even includes a notable failure to invest in infrastructure.

Next we saw how assets, primarily housing, have been part of a sustained bubble that is now bursting and will take many years to play out. When credit bubbles burst, they result in financial panics that end up destroying a lot of capital. Actually, that’s not quite right; this quote says it better:

Panics do not destroy capital; they merely reveal the extent to which it has been previously destroyed by its betrayal into hopelessly unproductive works.

—John Stuart Mill (1806–1873)

We learned that a bursting bubble isn’t something that’s easily fixed by authorities, because such attempts to “limit further damage” are misplaced. The damage has already been done; the capital has already been betrayed. It’s contained within too many houses, too many strip malls sold for too high prices, and too many goods imported and bought on credit. All of that’s

done

. What is left is figuring out who is going to end up eating the losses.

Then we learned that the most profound financial shortfalls of the U.S. government rest with the liabilities associated with the entitlement programs that are underfunded by somewhere between $50 trillion and $200 trillion dollars, neither of which are payable under the most optimistic of assumptions. A number of other governments around the globe are suffering similar shortfalls and constraints.

Throughout the last several decades, the economic numbers that we reported to ourselves were systematically debased until they no longer reflected reality. They were (and continue to be) fuzzy numbers. Bad data leads to bad decisions, and this is another reason why we find ourselves in our current predicament. The longer we continue to fib to ourselves, the worse the eventual outcome is likely to be.

Energy

Next we learned that energy is the source of all economic activity—it’s the master resource—and that oil is a critically important source of energy. Our entire economic model rests upon continuous growth and expansion. This means that it’s built around the flawed assumption that unlimited growth in energy supplies is possible, which, unfortunately, is an easily refuted proposition. Individual oil fields peak, as do collections of them. Peak Oil isn’t a theory; it’s simply an observation about how oil fields age.

We explored the tension that is obviously present between a monetary system that

must

grow and an energy system that

can’t

grow. All complex systems, of which the economy is a textbook example, owe their order and complexity to the energy that flows through them. Remove the energy, and by definition (and universal law), order and complexity will be reduced. Starving our economy of fuel risks crashing it.

The amount of fossil energy that we have at our disposal is fixed. Like a trust fund that earns no interest, it can only get spent once, and then it’s gone. Technology can help us to utilize that energy more efficiently, but it cannot create new energy.

The Environment

Finally, we noted that the environment, meaning the world’s resources and natural systems upon which we depend, is exhibiting clear signs that we’re approaching its limits. We’re finding ourselves in the position of needing to exploit the poorest-quality mineral ores, peaks in critical resources are being noted at a faster and faster pace, and we’re scouring the globe for the last few concentrated sources of primary wealth. We’re also depleting water in fossil aquifers at unsustainable rates, farmers are mining soils of essential nutrients, and our oceans’ rich ecosystems are suffering.

“Unsustainable”

Putting it all together, we come up with a story that’s very simple and virtually airtight:

Our present course is unsustainable.

Perhaps we can console ourselves with the idea that somehow we won’t reach the limits of our resources during

our

individual lifetimes, but we cannot argue that finite energy resources can last forever. If something is unsustainable, it will someday stop.

Many theoretical thinkers—including economists—reject the idea of limits, but individuals armed with the proper facts almost never do. The landmark modeling work done for

Limits to Growth

in the early 1970s was spot-on in virtually every respect, but economists and the media trounced on it because it did not fit their preferred view of a world without limits.

2

To economists at the time (whose ideas unfortunately still hold sway), resources just show up on time and as needed in response to “market demand,” and any intrusions on this tidy arrangement are often rejected out of hand.

If we had taken the time to heed the lessons in

Limits to Growth,

we would be in far better shape today, but we didn’t. In addition, we failed to take the lessons offered by Oil Shock I seriously, also in the 1970s. And so here we are with a lot more water in our stadium and the shackles still firmly affixed to our wrists.

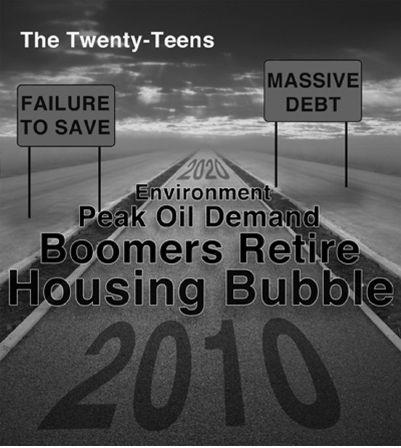

Convergence: The Timeline

If all we had to do was face any

one

of the predicaments outlined above, I’m confident that we would collectively do our best, respond intelligently, accommodate the outcome, and carry on. But if we allow for the possibility of facing several of these predicaments at once, the concern mounts considerably. A timeline stretching from 2010 to 2020 reveals a truly massive set of challenges converging on an exceptionally short timeframe (see

Figure 23.1

).

Placed on a timeline, we see that a bursting housing bubble began in 2008, just one year before the first wave of boomers entered retirement in the United States (January 1, 2009). Somewhere along the way, let’s call it 2015, Peak Oil and rising demand will conspire to outpace oil supplies, forcing an enormously expensive adjustment for every economy currently dependent on cheap oil. Soon thereafter, other depleted resources will peak, as their energy costs of extraction and refining will finally outweigh their economic utility. Unpredictable costs associated with a shifting climate are another potential demand on our limited budgets. And further limiting our options, a failure to save and invest, along with historically unprecedented levels of debt, will cast a shadow over the possible solutions or responses we might envision to all of the other predicaments.