The Day of Battle (63 page)

Authors: Rick Atkinson

Tags: #General, #Europe, #Military, #History, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War, #World War II, #World War; 1939-1945, #Campaigns, #Italy

Born in West Virginia, he was commissioned as a cavalry officer at West Point in 1911, then rode into Mexico with Pershing’s Punitive Expedition before being wounded in France, at Amiens. Lucas later commanded the 3rd Division at the time of Pearl Harbor and served as Eisenhower’s deputy in North Africa. This was his third corps command, including a brief stint as Bradley’s successor at II Corps before Marshall and Eisenhower picked him to replace Dawley at Salerno. Clark had privately preferred Matthew Ridgway, but accepted Lucas with a shrug.

Lucas drove a jeep named

Hoot,

quoted Kipling “by the yard,” and had accumulated several nicknames, including Old Luke and Sugar Daddy; at Anzio he would acquire more, notably Foxy Grandpa. Although he considered the Germans “unutterable swine,” one staff officer wrote that he “never seemed to want to hurt anybody—at times, almost including the enemy.” A British general thought Lucas possessed “absolutely no presence”; a Grenadier Guards commander confessed that when Lucas visited

his battalion billets above Naples Bay “our spirits sank as we watched this elderly figure puffing his way around the companies.” An odd rumor circulated that he was suffering ill effects from a defective batch of yellow fever vaccine.

For Lucas’s malady there was no inoculation. Empathy might ennoble a man, but it could debilitate a general. “I think too often of my men out in the mountains,” he had written during the winter campaign. “I am far too tender-hearted ever to be a success at my chosen profession.” A few days before boarding

Biscayne,

he added, “I must keep from thinking of the fact that my order will send these men into a desperate attack.” Upon hearing that

SHINGLE

had been authorized, Lucas portrayed himself as “a lamb being led to slaughter”; accordingly, he revised his last will and testament. The sanguine assurance of his superiors baffled him. “By the time your troops land, the Germans will have already pulled back past Rome,” Admiral John Cunningham, the British naval commander in the Mediterranean, had told him. Alexander claimed that the capture of Rome and subsequent hell-for-leather pursuit northward meant that “

OVERLORD

would be unnecessary.”

Could Alexander and others, he wondered, have additional intelligence that spawned such confidence? AFHQ asserted that it was “very questionable whether the enemy proposed to continue the defensive battle south of Rome much after the middle of February.” Fifth Army headquarters also claimed that enemy strength was “ebbing due to casualties, exhaustion, and possible lowering of morale.” Four days after landing at Anzio, the

SHINGLE

force would face no more than 31,000 Germans, according to Fifth Army analysts, and nearly two more weeks would pass before the enemy would be able to move even two more divisions from northern Italy. The designated military governor of Rome had already requested $1,000 for an “entertainment fund” in the capital.

Lucas beheld a different vision. His VI Corps intelligence analysts believed the Germans would muster a dozen battalions and a hundred tanks at Anzio on D-day, which would grow to twenty-nine battalions within a week and to more than five divisions and 150 tanks by D+16. VI Corps also estimated that, “even under favorable conditions,” reinforcement of the beachhead from the Cassino front “cannot be expected in under thirty days.” Lucas confided to his diary, “This whole affair has a strong odor of Gallipoli”—the disastrous British amphibious invasion of Turkey in 1915.

An old friend shared his premonitions. George Patton flew from Palermo to bid Lucas farewell before returning to Britain for his new army command. “John, there is no one in the Army I hate to see killed as much as you, but you can’t get out of this alive,” Patton told him. “Of course you

might be only badly wounded. No one ever blames a wounded general for anything.” Patton advised reading the Bible. To Lucas’s aide he added, “If things get too bad, shoot the old man in the back end.”

Lucas’s milquetoast demeanor obscured a keen tactical brain. He recognized, as did too few of his superiors, that the exalted ambitions for

SHINGLE

exceeded the means allocated to achieve them. Worse yet, those ambitions were muddled and contradictory, particularly with respect to the vital high ground northeast of Anzio, known as the Colli Laziali, or Alban Hills. Under Alexander’s instructions to Clark on January 12, the

SHINGLE

force was “to cut the enemy’s main communications in the Colli Laziali area southeast of Rome,” and to threaten the German rear on the Cassino front. The two Allied forces were then to “join hands at the earliest possible moment,” and hie through Rome “with the utmost possible speed.”

Yet the Fifth Army order issued later the same day instructed Lucas to “seize and secure a beachhead at Anzio,” then to “advance on Colli Laziali.” Clark remained deliberately vague about whether VI Corps was to surmount the Alban Hills or simply amble toward them. Through painful experience, the Fifth Army commander now expected the Germans to fight hard, first for the beachhead, then for the approaches to Rome. Alexander might wish otherwise, but he was “a peanut and a feather duster,” as Clark told his diary in an odd, impertinent blend of metaphors.

In a private message, Clark advised Lucas to first secure the beachhead and avoid jeopardizing his corps; if the enemy proved supine, then VI Corps could lunge for the hills to cut both Highways 6 and 7, the main supply routes from Rome to Kesselring’s forces on the Garigliano and at Cassino.

“Don’t stick your neck out, Johnny,” Clark told Lucas. “I did at Salerno and got into trouble.” He added, “You can forget this goddam Rome business.”

Fantasy and wishful thinking suffused Alexander’s

SHINGLE

plan; Clark added realism, flexibility, and insubordinate arrogance. Now confusion clattered down the chain of command. The XII Air Support Command, which would provide the invasion force with air cover, assumed that

SHINGLE

was intended to “advance and secure the high ground.” The British 1st Division commander, Major General William R. C. Penney, also had the impression that his troops were to “advance north towards fulfillment of the corps mission to capture Colli Laziali.” But Lucas’s Field Order No. 19, dated January 15, lacked a detailed plan beyond the landings; Truscott’s 3rd Division, for example, was told only to establish a beachhead and to prepare to move, on order, toward the hill town of Velletri. A baffled General Penney told his diary on January 20, “Corps at least talking of plans to

break out of beachhead.” Small wonder that Clark’s deputy chief of staff, General Sir Charles Richardson, later observed, “Anzio was a complete nonsense from its inception.”

One other issue added to Lucas’s unease: the rehearsals for

SHINGLE

, on the beaches below Salerno, had been fiascoes. The British failed to disembark either brigade or division headquarters. The Americans, in an exercise code-named

WEBFOOT

, did worse. The Navy abruptly changed the landing beach, and only eleven of thirty-seven LSTs showed up. Rough weather and navigation errors on the night of January 17 kept the fleet fifteen miles offshore, and forty DUKWs making for land sank in the high seas, taking twenty-one howitzers, radio gear, and several men to the bottom. “I stood on the beach in an evil frame of mind and waited,” Lucas reported. “Not a single unit landed on the proper beach, not a single unit landed in the proper order, not a single unit was less than an hour and a half late.”

Truscott was so furious about the preparation for Anzio that he wrote Al Gruenther, “If this is to be a forlorn hope or a suicide sashay, then all I want to know is that fact.” Before boarding

Biscayne,

Truscott—with Lucas’s blessing—also sent Clark an account of

WEBFOOT

. The army commander was appalled at “the overwhelming mismanagement by the Navy.” But he told Truscott, “Lucian, I’ve got your report here and it’s bad. But you won’t get another rehearsal. The date has been set at the very highest level. There is no possibility of delaying it even for a day. You have got to do it.”

Italy for eons had been a land of omen and divination, of portents and martial prophecy. During earlier campaigns on the peninsula it was said that two moons had risen in the sky, that goats grew wool, that a wolf pulled a sentry’s sword from its scabbard and ran off with it. It was said that scorching stones fell like rain, that blood flowed in the streams, that a hen turned into a cock and a cock into a hen, that a six-month-old baby in Rome shouted, “Victory!” It was said that soldiers’ javelins in midflight had burst into flame.

Modern men had no use for bodings or superstition, of course. Still, it was a bit surprising that the

SHINGLE

force ignored the ancient sailors’ injunction against sailing on a Friday, the day of Christ’s crucifixion. But at 5:20

A.M

. on Friday, January 21, the Anzio flotilla weighed anchor and made for the open sea after first feinting south. Some soldiers fingered their rosary beads or huddled with a chaplain. Others snoozed on deck or basked in the sun, scanning the distant shore for the Temple of Jupiter at Cumae, where an Allied radar team played a recording of “Carolina Moon.” “Most talk is of home and regular G.I. stuff,” an airman wrote in

his diary. Steaming at a languid five knots, the convoys “look more like a review than an invasion armada,” one British lieutenant wrote.

In his cabin aboard the crowded

Biscayne,

Lucas spread his bedroll and shoved his kit into a corner. Truscott, who had gone to have his throat painted, would sleep on the couch. “More training is certainly necessary,” Lucas wrote in his diary, “but there is no time for it.” He had resigned himself to his fate. “I will do what I am ordered to do, but these Battles of the Little Big Horn aren’t much fun.” The show must go on.

ERDITION

“Something’s Happening”

O

NLY

the bakers were astir in the small hours of Saturday, January 22. The fragrance of fresh bread wafted through the dark streets from the wood ovens in Margherita Ricci’s little shop, past the shuttered tobacco stall and the bronze statue of Neptune riding a huge fish. In Nettuno and adjacent Anzio—the woodlands of the Borghese villa separated the sister towns—bakery workers were among the few citizens still permitted in the coastal exclusion zone established by the Germans four months earlier. More than fifteen thousand exiles lived in shanties in the nearby Pontine Marshes or on the slopes of the Colli Laziali. Anyone caught within three miles of the coast risked a bullet to the nape, usually delivered against a wall in the Via Antonio Gramsci, where the condemned were told to turn their heads for a final glimpse of the sea before the fatal shot.

Dusted with flour and smelling of yeast, Orlando Castaldi shoved his flat wooden peel beneath a batch of rolls browning in the oven. Castaldi had been in Sicily during the Allied invasion six months earlier, eventually fleeing to Nettuno, where his brother and uncle worked in another bakery just two hundred yards north, in the Via Cavour. Brief but plucky resistance to the German occupation in September had been punished with executions, deportations, and the usual kidnapping of able-bodied men for labor battalions. Those consigned to the marshes had endured a bitter early winter, using ashes for soap and living on the loaves carted out from Ricci’s each morning. Some chanced reprisals by sneaking into Rome to trade gold earrings or family linen for black-market pasta or a few liters of cooking oil. Allied bombing along the coast had gnawed the waterfront and forced the removal of the Madonna of Graces—an ornate wooden statue of Nettuno’s patron—to a basilica in Rome for safekeeping.

Castaldi cocked his head, holding the paddle at high port like a halberd. Through the open window came a noise from the sea, a distant clamor. “Keep still a moment,” he told two colleagues. “Something’s happening.” Clanking metal and the thrum of engines carried on the night. Castaldi

recognized the sound, from Sicily. “I can hear them,” he said. “I can hear them. The Americans are coming!” Grabbing his jacket, he yanked down the window blinds and sprinted through the door to alert his brother and uncle. As he rounded the corner into the Via Cavour, a brilliant light bleached the night sky and the ground trembled as if Neptune himself had impaled the earth with his trident.

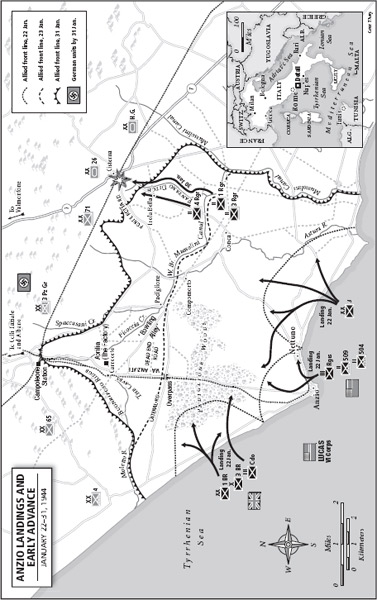

The Americans were indeed coming, and so too the British. Three miles offshore the armada had dropped anchor at 12:04

A.M

., four minutes late, in a dead calm and diaphanous haze. Scout boats puttered toward shore and at 1:50

A.M

., just as young Castaldi darted into the street, a pair of British rocket boats opened fire with fifteen hundred 5-inch projectiles intended to cow coastal defenders and detonate beachfront mines. The five-minute bombardment “made a tremendous noise, achieved no good results, and was prejudicial to surprise,” an intelligence officer reported. Only silence answered the barrage, and shortly after two

A.M

. the first infantrymen swarmed onto the beach, bent on adding injury to the rockets’ insult.

Before the war, before the killings and the expulsions and those last sad looks at the sea, Anzio-Nettuno had been a thriving resort, just two hours from Rome by fast Fiat, with a fine harbor and garish bathhouses. In waterfront eateries known for their

zuppa di pesce,

patrons could watch the fireworks on feast days. Nettuno had grown a bit larger in modern times, but Anzio, ancient Antium, had greater notoriety. Nero and Caligula had both been born here—the former’s fiddling during the conflagration of Rome was said to have occurred in Antium’s theater—and the patrician rebel Coriolanus supposedly was slain here in 490

B.C

. Silver-throated Cicero owned a villa in Antium; Trajan had enlarged the port; and various emperors bred elephants along the coast. Antium had worshipped the goddess Fortune as the town’s protectress, but she proved inconstant. The harbor silted up during Rome’s decline, and piracy eclipsed tourism. Through the centuries, the goddess alternately smiled and scowled capriciously.

Now her temper would be tested again. Anchoring the VI Corps’ left flank, the British splashed ashore five miles up the coast on Red, Green, and Yellow Beaches. A few desultory rounds of German artillery plumped the shallows, but naval gunfire soon answered and the only resistance across the shingle came from mines and soft sand. Much bellowing with bullhorns accompanied the landings: a subsequent analysis advised that “no amount of shouting through loud-hailers will induce troops to advance through a minefield.” British lorries, lacking four-wheel drive,

tended to bog down in the narrow dune exits—“The waste of time was fantastic,” a beach commander lamented—and tempers flared. When a landing craft coxswain scraped the hull of the flagship H.M.S.

Bulolo,

a naval officer roared, “Don’t stand about like a half-plucked fowl. Cast off!”

Soon enough twelve-foot lanes were cleared through the mines and marked with luminous paint. Hundreds and then thousands of Tommies scuffed into the piney Padiglione Woods, searching in vain for an enemy to overrun. Three Germans were found sleeping in a cowshed amid plundered bottles of Italian perfume and nail polish. One surrendered in his underwear, though the other two escaped in an armored car. “It was all very gentlemanly, calm and dignified,” the Irish Guards reported. Carrying a large black umbrella as he arrived in a DUKW, the Irish Guards commander “stepped ashore with the air of a missionary visiting a South Sea island and surprised to see no cannibals.”

No cannibals appeared on the right flank either. Truscott’s 3rd Division made land just south of Nettuno, while Darby and his Rangers beat for the white dome and terraces of the Paradiso, a casino overlooking Anzio harbor. Most troops came ashore wetted only to the knees, if not completely dryshod. A few spurts from a flamethrower encouraged shrieking surrenders in an antiaircraft battery; nineteen enemy soldiers emerged hands-up from a bunker that still sported a scraggly Christmas tree. Engineers found more than twenty tons of explosives stuffed in the docks and doorways, but winter weather had corroded the charges and a new German plan to blow up the mole had not yet been effected. Prisoners trickled in, including Wehrmacht rustlers captured while searching for cattle to feed their unit.

After watching through field glasses from the

Biscayne,

General Lucas advised his diary that he “could not believe my eyes when I stood on the bridge and saw no machine gun or other fire on the beach.” At 3:05

A.M

. he sent Clark a coded radio message: “Paris-Bordeaux-Turin-Tangiers-Bari-Albany,” which meant “Weather clear, sea calm, little wind, our presence not discovered, landings in progress.” Later in the morning Lucas signaled “No angels yet, cutie Claudette”: No tanks ashore, but the attack was going well.

It continued to go well through the day. Truscott made for shore in a crash boat at 6:15

A.M

., mute with laryngitis and so miserable from his inflamed throat that he lay down for a nap in a thicket near the beach. His men hardly needed him. All three regiments pushed the beachhead three miles inland, exchanging a few gunshots with backpedaling German scouts, and then blowing up bridges across the Mussolini Canal to seal the right flank against a panzer counterattack that never came.

By sunrise, at 7:30, Rangers occupied Anzio; paratroopers soon after reported that Nettuno also was secure. Local bakers, including the gleeful Orlando Castaldi, were ordered to bank their oven fires to prevent German gunners from aiming at the smoke. Soldiers liberated six women found chained to tethering rings in the Piazza Mazzini stable; they had been sentenced to death four days earlier while returning by train from Rome with black market food purchased in the Piazza Vittorio. The Americans gave them powdered milk, chocolate, and underwear, then sent them home.

DUKWs rolled through the streets like parade floats. Prisoners in long green field coats trudged to cages on the beach, “dusty, sweaty and noncommittal,” as one witness put it. “Move on, superman,” a GI jeered. Outside the former German command post, on a large sign that read

KOMMANDANT

, someone scribbled:

RESIGNED

. A few more shells fell along the waterfront and the Luftwaffe staged an ineffectual raid. “Maybe the war is over and we don’t know it,” said a lieutenant colonel. A GI added, “It ain’t right, all right. But I like it.” MPs tacked up road signs, and soon jeeps and trucks clotted the streets. An old woman stood at an intersection outside town, kissing the hand of every soldier tramping past. As one private reported, “She did not miss a man.”

Success brought sightseers to the beachhead. At nine

A.M

., to the trill of a bosun’s pipe, Alexander and Clark clambered aboard the

Biscayne

from a patrol boat that had whisked them north from the Volturno. Lucas summarized the news with a smile: resistance negligible, casualties light, most assault troops already ashore. Anzio’s port was in such fine condition that at least a half dozen LSTs could berth simultaneously, and the first would unload this afternoon.

From

Biscayne

the boating party traveled by DUKW to the beach. Clark—immaculate in peaked cap, silk scarf, and creased trousers—inspected the 3rd Division and pronounced himself pleased. Poor Truscott croaked his thanks. Alexander—no less comely in red hat, fur-trimmed jacket, and riding breeches—motored among the British battalions in the turret of an armored car. To a Scots Guardsman he resembled “a chief umpire visiting the forward position and finding things to his satisfaction.” General Alex, in fact, told a British colonel precisely that: “I am very satisfied.” Reconvening on

Biscayne,

the two men complimented Lucas on his derring-do, then hopped back into the patrol boat and sped off toward Naples, leaving neither orders nor a sense of urgency in their wake. As one wit commented, “They came, they saw, they concurred.”

Left alone to command his battle, Lucas decamped from

Biscayne

to Piazza del Mercato 16, a two-story villa in Nettuno with four bedrooms and

an upstairs fireplace. Sycamores ringed the little square, framing the sculpture of Neptune straddling his fish. The previous occupant of number 16, the German commandant, had bolted so quickly—only to die on the beach in the early minutes of the invasion—that a sausage and half-empty brandy glass remained on the dining table.

The Allies had won what they least expected to win: complete surprise. By midnight on D-day, 27,000 Yanks, 9,000 Brits, and 3,000 vehicles would be ashore in a beachhead that was fifteen miles wide and two to four miles deep. Only thirteen Allied soldiers had died. As one paratrooper wrote, most soldiers found it “very hard to believe that a war was going on and that we were in the middle of it.”

Lucas also found it hard to believe. From the north window of number 16, he could plainly see his prize. Fifteen miles distant, the Colli Laziali rose above the myrtles and umbrella pines, burnished by the setting sun that kissed the red tile rooftops before plunging into the Tyrrhenian Sea. White haze scarped the hills, which rose three thousand feet above the coastal plain in a volcanic massif nearly forty miles in circumference. Wind-tossed chestnut groves softened the tufa ridges, providing haunts for cuckoos and dryads and ancient enchantresses. Here too lay Castel Gandolfo, the pope’s summer home, where in years past the pontiff could have been seen riding a white mule among the cypresses, trailed by cardinals robed in scarlet.

Dusk sifted over the beachhead. Lights winked on in up-country villages, and convoy headlights drifted in tiny chains across the hills like ships steaming on the far horizon. In his tidy, contained cursive, Lucas wrote, “We knew the lights meant supplies coming in for the use of our enemies, but they were out of range and nothing could be done about it.”

Thirty-four miles from this window lay Rome, known in Allied code-books as

BOTANY

. Two routes crossed the “hinterland,” as the British called the landscape beyond the beachhead. One road angled northeast from Nettuno, across the Pontine Marshes to Cisterna, twelve miles distant, and then fifteen more miles to Valmontone, astride Highway 6 in the Liri Valley. The other road, known as the Via Anziate, ran due north for almost twenty miles from Anzio to intersect Highway 7, the twenty-three-century-old Appian Way, at Albano.

Both roads led to glory, and Lucas intended to follow both. The world seemed to believe that

BOTANY

was all but his. The Sunday edition of

The New York Times

reported the Allies “only sixteen miles from Rome.” Radio broadcasts heard in the beachhead were even more optimistic. “Alexander’s brave troops are pushing towards Rome,” the BBC reported on Sunday, “and should reach it within forty-eight hours.”

Neither the

Times

nor the BBC had consulted Field Marshal Kesselring.