The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland (11 page)

Read The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland Online

Authors: Jim Defede

Tags: #Canada, #History, #General

Sensing their need for distraction, folks at the legion were taking turns sitting with the anguished couple. Karen Johnson, the wife of the legion’s bar manager who was eight months pregnant, visited each day so she could spend time with Hannah. Her pregnancy gave the two women something to talk about, from one mother to another.

And then there was Beulah Cooper. Treasurer of the ladies’ auxiliary for the Royal Canadian Legion in Gander, Cooper had been at the hall almost nonstop since September 11. She had three of the passengers staying in her home and had let about a dozen others come over to use her shower.

On Wednesday she convinced Dennis, his nephew Brendan Boyle, and his girlfriend. Amanda, who had been traveling with the older couple, to come to her home, shower, and relax for a couple of hours away from the crowded and noisy hall. Hannah, however, refused to leave. Cooper, a retired government employee, assured her that the folks at the legion would pass along her—Cooper’s—number, but Hannah didn’t want to take the chance. Except for the two hours each day she spent going to morning and evening Mass, Hannah did not set foot outside the legion hall.

If Hannah wouldn’t leave, Cooper decided to try to find other ways to help. She felt a special affinity for Hannah because her son is a volunteer firefighter in Gander. Whenever she hears the sirens of a fire truck, she worries about him. She tried to imagine multiplying that feeling a thousandfold and then having to live with it for days on end.

She knew she couldn’t take away the other woman’s pain, but she might be able to distract Hannah from it for a few minutes at a time. An unreserved woman, Cooper was boisterous and outgoing. And when it came to telling jokes, Cooper was a Newfie Shecky Greene. She loved giving a joke life, and sitting alongside Hannah, she’d fire away:

A fella comes out of a bar after having one too many drinks and he runs into a priest. “Hey,” the fella says, “look at your collar, your shirt’s on backward.”

“I’m a father,” the priest explains to the man

.

“So am I,” the fella replies

.

“Yes, but I’m the father to many,” the priest offers

.

“Well, in that case,” the fella says, “you should have your pants on backward instead of your shirt.”

When Cooper would finish a joke, Hannah would smile, sometimes even laugh, which only encouraged Cooper to tell more.

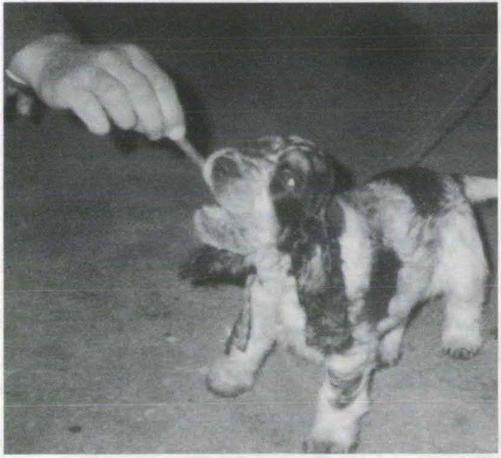

A treat for Ralph.

Courtesy of Linda Humby

E

xcluding the crews, there were officially 6,132 passengers on board the thirty-eight flights, but Bonnie Harris feared there were actually more. Had anybody in authority bothered to check the cargo holes in the belly of the planes? Or were they too overwhelmed to search these jumbo jets thoroughly? All night Tuesday she imagined the worst. She kept picturing hidden travelers lying in the darkness of the planes, desperate to get out, ready to do God knows what.

Bright and early Wednesday morning, she decided to find out for herself. She didn’t trust the people running the operation to know what was really going on, so she called the work area for the ground crews directly.

“Do you have any animals on these planes?”

Just as she suspected, they did. The manifests for twelve of the flights showed the planes were carrying an assortment of animals, including at least nine dogs, ten cats, and a pair of extremely rare Bonobo monkeys. Harris asked if anyone had made arrangements to feed or provide water for any of the animals, who, by this point, had been cooped up in tiny cages aboard the planes for almost twenty-four hours. The answer was no. That was all Harris needed to hear. For five years she’d worked for the local chapter of the Society for the Protection of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) and was currently the manager of the town’s only animal shelter.

“You just can’t leave them like that,” she complained.

Harris called one of her assistants, Vi Tucker, and the two women loaded up a truck with pet food, water, cleaning supplies, and anything else they thought they might need, and lit out for the airport. Once they arrived, they began sizing up the situation. The animals were stowed away in cages in the same compartments as the luggage. As Harris went around taking a quick look inside each of the planes, she knew these animals were going through their own emotional ordeals. In some cases, Harris couldn’t even see the animals, as they were buried behind mounds of suitcases. But she could hear them crying and barking.

At first she tried to convince airport officials to let her and Vi take the animals off of the planes so they could be fed and cared for properly. A representative for Canada’s agriculture department, however, refused even to consider it. The official was worried the animals might get loose and introduce some strange disease into the country. Rather than go to war with the bureaucrat, Harris and Tucker and another SPCA worker, Linda Humby, decided to make the best of the situation.

One at a time they crawled into the belly of the airplanes, tunneling their way through the mountains of bags, to reach each animal. As best they could, they would clean the cage and then lay out some food and water.

In addition to being cramped, it was also hot. And it smelled. The worst part, though, was seeing the animals, who were obviously scared and disoriented. The women looked for tags on each of the cages that might give the animal’s name, so that the animal might hear something reassuring. Since they were all coming over from Europe, the woman thought, these pets might not understand a lot of English, but every dog and cat can recognize its name.

On a British Airways plane, they found a cat that had a pill taped to the front of its cage. The cat was apparently epileptic and needed regular medication to ward off seizures. Aboard a Lufthansa flight were two Siamese cats and a ten-week-old purebred American cocker spaniel with the name tag

RALPH

pinned to the door. The women fell in love with Ralph immediately.

As the woman went from one plane to the next, they became increasingly frustrated. It would take them more than ten hours to visit the twelve planes the animals were on. By the time they finished, they were covered in sweat, dirt, and an assortment of other stains they didn’t even want to think about.

“This isn’t going to work,” Harris told Humby. “It took us all day to feed them just one meal.”

Some of the animals—such as the epileptic cat—would need medication on a regular basis. The only good news was that they didn’t have to worry about the monkeys. The Bonobos were on their way from Belgium to a zoo in Ohio and were being tended to by their handler. Nevertheless, the women were going to need more help with the dogs and cats. Most of all, they needed to get those animals off the plane. Desperate, they called the government’s regional veterinarian, Doug Tweedie.

Doc Tweedie was stunned when Harris told him what was happening. On Tuesday, he had been forty miles away in Bishop Falls tending to a sick cow when he heard about the terrorist attack in the United States and learned of the diverted flights to Gander. Suspecting there might be animals on some of the planes, he asked his wife to check into it. When she called Gander’s town hall on Tuesday, she was told there were no animals on any of the flights—a message she passed on to her husband.

Now he suddenly learned there were animals on those planes. And after hearing the horror stories from Harris, Tweedie leaped into action. After several phone calls to his superiors in St. John’s, a deal was reached whereby the animals could be taken off the plane and kept in a vacant hangar where the women could care for them.

“Thank God,” Humby said when she heard the news from Doc Tweedie. She knew if they hadn’t received permission to remove the animals, some of them would have certainly died.

A

s the heroines of the SPCA continued their mission of mercy, Constable Oz Fudge was busy honoring a long-distance request from a fellow police officer. Earlier in the day he received a phone call from Sheryl McCollum, an investigator with the Cobb County Police Department in Marietta, Georgia.

“I have a favor to ask,” McCollum began.

“I’m cheap and I’m easy and I’ll do whatever you want,” Fudge replied.

“My sister Sharlene Bowen is on one of the flights.” McCollum explained. “She’s a flight attendant with Delta. She’s staying at the Irving West, room 214. I want you to go down there and give her a hug and tell her that we miss her and we can’t wait for her to come home.”

“All right,” Fudge said.

“Now, you remember that a promise is a promise,” McCollum said.

“Yes, my dear.” Fudge said. “Don’t worry about a thing. I promise.”

Fudge drove to the hotel, but the forty-five-year-old Bowen wasn’t there. He left her a note, cryptically saying he had a message for her. He also left her a present, a Gander Police Department patch.

While Fudge was visiting the hotel, Bowen was walking around town. A flight attendant on Delta Flight 15. Bowen was the middle child in a family of five sisters. All of the sisters were extremely close; none of them had heard from Bowen since her plane was diverted to Gander.

Bowen had managed only a brief phone call to her husband, using the cell phone of one of the passengers. When she first arrived at the hotel from the plane, she tried again, but all of the circuits were busy. Rather than sit in the room and wait for the phones to work, Bowen decided to take a look around. And after thirty hours on the plane she needed to stretch her legs and get a little fresh air.

Back in Georgia, McCollum wasn’t willing to wait. Using her detective skills, she had tracked down her sister’s whereabouts and then called Fudge.

An hour or so after Fudge departed. Bowen returned to the hotel and discovered the note and the patch waiting for her at the front desk, and assumed they must have been some sort of a message for the crew from Delta. The town’s municipal building was only a couple of blocks away, and thinking the police department might be housed inside. Bowen, along with the plane’s pilot and several of her fellow crew members, walked over.

Fudge wasn’t there, but the group did run into Mayor Claude Elliott. The mayor explained that Fudge was working a security detail at the airport and would contact Bowen later. In the meantime, Elliott asked if the Delta crew would like a tour of his town. They all accepted and then piled into the mayor’s car. He drove them to Lake Gander and then out to the airport to see the planes. It was the first time Bowen had a good look at all of the aircraft that had been diverted to Gander.

The mayor then took them over to the community center. Bowen couldn’t believe the amount of supplies people were donating. The mayor was extremely proud of his town’s efforts. He even took them to the local brewery, where they were given free samples of beer. As the mayor continued his guided tour, his cell phone rang.

“Okay,” he said, “I’ll swing by my house and pick up my clubs. See you soon.”

It was the manager of the local golf course, Elliott explained. They were allowing passengers to play for free, but the course didn’t have enough spare sets of clubs to outfit everyone. The course manager was calling his regular customers, hoping they would bring their clubs to the course for the passengers to borrow. So far everybody the manager contacted had said yes.

By the time Bowen returned to the hotel several hours later, she found another note from Fudge and a police department baseball cap. This time, though, Fudge had left his phone number.

“Don’t move,” he implored when she called. “I’ll be there in five minutes.”

Three minutes later Fudge arrived. Bowen was standing in the lobby, still not sure why he needed to talk to her. The constable walked up to her and, without saying anything, wrapped his arms around her and squeezed tight.

“That’s from your sister,” he finally said.

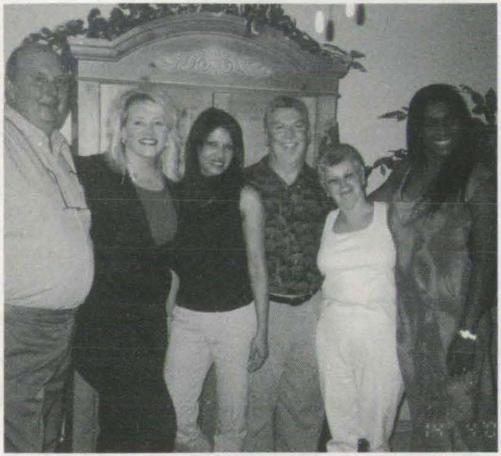

George, Deb, Lana, Bill, Edna, and Winnie reunite in Houston, April 16, 2002.

Photo courtesy of Lana Etherington

T

wenty-four hours after the attack on the World Trade Center, there were still passengers on board a handful of planes in Gander waiting to be processed. Despite the delay, the 116 people aboard Continental Flight 5 from London to Houston were in amazingly good spirits. This was largely attributable to three factors. First, everyone recognized that in light of the tragic events in the United States, they had no right to complain. Second, they understood that griping wouldn’t do any good anyway, so they might as well make the best of it. And third, the flight attendants had unlocked the liquor carts and were letting everyone pour their own drinks for free.

Once the sun went down on Tuesday, the plane developed the vibe of a freewheeling United Nations cocktail party, with passengers mixing, mingling, and imbibing. It was during this revelry that Deborah Farrar sipped her first gin-and-tonic. Her trip overseas had been full of firsts for the twenty-eight-year-old Texan—the most significant being that it was the first time she’d ever been outside the United States. The whole point of this vacation was to take chances, experience new things, and expand her horizons; and although the reason for her current predicament was tragic, she found herself enjoying the company of the other passengers.

Ten days earlier she’d taken off from her job as an account executive for an information technology firm in Houston and had flown off to Europe all by herself. She went to Oslo and Bergen in Norway for the first six days before ending up in London. She was due back at work later in the week but now found herself in a place she had never heard of before and in the midst of something she wasn’t quite sure how to handle.

When the plane landed Tuesday afternoon and the pilot announced what happened in New York, Farrar broke down in tears. She wanted to talk to her family, hear their voices, and let them know she was okay, but none of the phones on the plane had worked. Eventually, a cell phone belonging to one of the passengers in first class locked onto a usable signal, and the man let everyone on board make a call. A line stretched down the aisle of the aircraft as one by one his fellow passengers and the flight’s crew members talked to loved ones back home for a few minutes. Five hours after landing, Farrar reached her father.

Being able to call home had had a liberating effect on most of the passengers, and the tension on the plane lifted. Rather than worrying about family members who might be worried about them, they mainly concentrated on piercing the boredom of being trapped on a plane all night. Also, no one on board seemed to have a direct connection to the tragedy—no family members in New York or Washington who might be missing or dead. Their only real link was the bits of news they would receive.

Inside the cockpit, the pilot’s radio was tuned to a news station broadcasting nonstop reports from the United States. From time to time passengers would poke their heads in to listen. Whether the pilot realized it or not, leaving the cockpit door open proved to be incredibly reassuring for those on board. Rather than feeling alone and isolated, they knew they had access to the latest news without having it forced on them. It was up to each passenger to decide how immersed in the details of the day’s events he or she wanted to be.

Once the flight attendants served the last of the food, they rolled out the carts containing those marvelous miniature bottles of booze. The attendants set them up by the back of the plane and then walked away. A few passengers promptly donned aprons and played bartender. So while those interested in listening to news reports huddled near the cockpit, those who wanted to escape flocked to the rear of the aircraft.

The mood was set by a group of wealthy oilmen from first class, One in particular, Bill Cash, was feeling especially social. Cash owns a company that helps build offshore oil platforms. He had been born in England but married a girl from Alabama, and they now lived in Houston. At fifty-one, Cash was the kind of fellow who could start a party just by walking into a room. As far as he was concerned, a stranded jumbo jet was as good a place as any for a good time.

It didn’t take long for him and Deb to become friends. She proved to be just as outgoing as he was. Her gin and tonic was the idea of one of Cash’s fellow businessmen and it sounded good to her. When one of the flight attendants heard it was the first time Deb had ever had this particular libation, she raced off to the galley. Returning a few moments later, she plopped a wedge of lime in Deb’s drink.

“You can’t have your very first gin and tonic without lime,” the flight attendant said. “It wouldn’t be right.”

Farrar was awestruck by the different people she met. Two of the women she befriended on the plane were Lana Etherington and Winnie House. The first thing Deb noticed about Winnie was how strikingly beautiful the twenty-six-year-old was. Winnie was tall and slender, like a model. And her hair, tied in braids, stretched all the way down to the small of her back. Born in Asaba, Nigeria, where her father is a village chieftain, Winnie spent a lot of her time growing up in London. Fluent in both English and her native language of Igbo, she also spoke a little French. She attended college in Oklahoma and had recently settled in Houston. On September 11, she was flying home to Houston after visiting her sister in London.

Lana was also from Africa. She had grow up in what was then known as Rhodesia and received a law degree from the University of Rhodesia. She left the former British colony in 1980 as the white-controlled government was being replaced by Robert Mugabe, a guerrilla-leader-turned-dictator who renamed the nation Zimbabwe. From Africa, Lana moved to the Middle East, where she worked for Pan American Airways as an executive secretary. While living in Dubai for five years, she married an American who worked for an oil company. Together for nineteen years, the couple now lives in Houston with their two children. The Lone Star State hasn’t made much of a linguistic impression on Lana. She continues to speak with a proper British accent.

Deb, Winnie, and Lana made an eclectic trio: an innocent Texas Aggie, a Nigerian princess, and a globe-trotting mom.

By the time Wednesday morning rolled around, the plane had been wrung dry of alcohol and most of the passengers had managed only a couple of hours’ sleep. Continental Flight 5 was the thirty-fifth plane to be emptied. Bleary-eyed, Deb and her new friends climbed onto yellow school buses for the ride to the terminal building, where they would be taken through Canadian customs and then passed along to the Red Cross for processing. Twenty-nine and a half hours had passed from the time they boarded in London to the time they finally stepped off the plane in Gander.

Most of the shelters in town were already filled when Flight 5 was ready to leave the airport, so they were sent thirty miles down the Trans-Canada Highway to Gambo, a town of 2,300 people located at the confluence of the Gander River and Freshwater Bay. This is the southern edge of Newfoundland’s scenic Kittiwake coast, a series of small fishing villages, inlets, and islands that jut into the North Atlantic. The Kittiwake coast stretches from Laurenceton up to Twillingate and Fogo Island, and then down to Port Blanchard. In the late spring and early summer, when the polar ice cap begins to break apart, visitors come to the area to watch the massive icebergs flow into the Atlantic.

For nearly a century, from the 1860s until the 1950s, Gambo was the hub of the area’s logging operations. The daily harvest of spruce, fir, and pine trees would be floated down the river to the sawmills in Gambo, where they were cut and then loaded onto railcars. The Great Fire of ’61 changed all that. Tens of thousands of acres went up in flames, and with it the economy of Gambo. All that’s left is an empty train trestle, a reminder of the town’s storied past.

As they drove along the winding roads leading into Gambo, Lana was reminded of the hills and valleys of northern England. It was all so quaint and rural. They arrived at the Salvation Army church early Wednesday afternoon. It seemed as if the whole town had come to welcome them. There was a big pot of beef stew and sandwiches waiting on one table. At another, there were seven women all in line, serving freshly brewed tea in little teacups.

Inside, a television was on, but Deb, Lana, and Winnie ignored it, opting instead to use the phones in the church to call their families. When Lana finished talking to her husband, she noticed that one of her fellow passengers, Mark Cohen, had gone outside to have a cigarette. A closet smoker who hides her habit from her children, Lana joined him. Whether it was conscious or not, Lana made the decision not to see the devastation on television. The fresh air and warm sun on her face had invigorated her. After she’d spent almost thirty hours cooped up on planes and buses, the last thing she wanted to do was to sit indoors and watch the news. She suggested to Mark that they find Deb and Winnie and explore the town a bit. He agreed, and the four of them were soon on their way.

Their plan was simple: find Gambo’s one pub. Walking down the road, they made quite a sight. After a few minutes a red van, driven by a man who appeared to be in his early sixties, pulled up alongside them.

“Are you the plane people?” asked the driver, George Neal.

The group nodded, not quite sure what to make of him.

“Do you want to come around for coffee?” he suggested. “I live just down the road. I can give you a lift.”

The foursome looked at one another and through a series of discreet nonverbal gestures—a raised eyebrow, a few tiny head shakes, and an assortment of grimaces—quickly came to the conclusion that it probably wasn’t a good idea to get into a complete stranger’s van. Politely begging off, they told George they were fine and wanted to walk. George said he understood, but if they changed their minds, or if they ever needed a ride somewhere, to just stop by his house. He pointed out where he lived and drove off.

Standing by the road, they all laughed. After all, there must be at least a dozen horror movies that start off with just this type of scenario—a group of friends, out in the middle of nowhere, who hitchhike a ride from a kindly old man and end up struggling for their lives. After walking a few more minutes, they spotted the town store. They pooled their cash—no credit cards accepted—and bought ice cream and potato chips and bottled water. They asked the clerk how far it was to the pub. The answer shocked them. It was still a good two miles away. Gambo may not have had many people in it, but it is long and narrow and winds with the river. The church where the passengers had been dropped off was on the western edge of town, and the pub was on the eastern side. The sun that had felt so good a short time before was now feeling a bit oppressive. None of them wanted to hike another two miles in eighty-degree weather, but they refused to give up on their quest for the next round of cocktails. It was clear what they had to do.

Following the van driver’s directions, they approached a large house with off-white vinyl siding and white trim. Mark joked that he would protect them if there was any trouble, and the women laughed nervously. They noticed an older woman standing in the driveway.

“George invited us over for coffee,” Deb said.

“You must be the plane people,” the woman replied, introducing herself as George’s wife, Edna. “Come on in, my dears.”

George was inside and was thrilled to see them. As he and Edna scurried off to the kitchen, Deb, Lana, Winnie, and Mark found themselves staring at the couple’s big-screen television. It was late Wednesday afternoon, and for the first time they all saw the images of destruction in New York. Until now they had done a good job of distancing themselves from the terror, but as soon as they saw news reports and those pictures, the reality of the last twenty-four hours hit them, hit them in such a way that they could no longer ignore it. Shocked. Shaken. Horrified. There were no words to describe what they were feeling. Deb broke down in tears in the living room. Winnie ran into the bathroom to cry. The others just stood there speechless.

For now at least, the party was over.