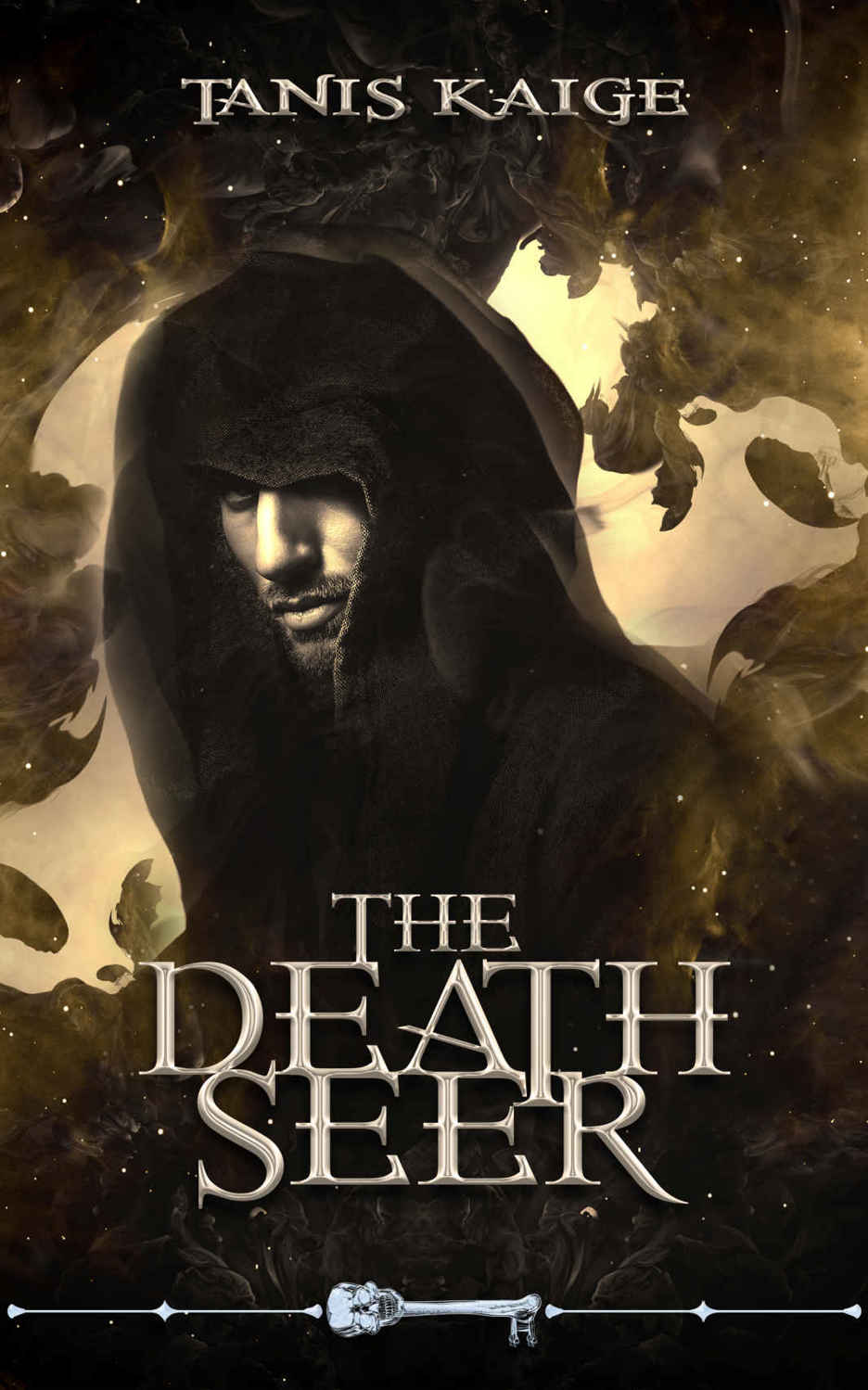

The Death Seer (Skeleton Key)

Read The Death Seer (Skeleton Key) Online

Authors: Tanis Kaige,Skeleton Key

The Death Seer

Tanis Kaige

Copyright © <2016>

All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Digital Edition. Personal use rights only. No part of this publication may be sold, copied, distributed, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical or digital, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Cover Design by

J.M. Rising Horse Creations

Edited by Cole Editing Services

Connect with the author

ISBN:

153319372X

ISBN-13:

978-1533193728

Table of Contents

Ten years ago, two things happened. First, a little boy vanished. This was significant to no one but me, considering that the boy’s mother and only family member had died only hours before he went missing. He was ten. I was ten. He was homeschooled. I used to sneak up to his bedroom window to keep him company. His mother made him wear a blindfold and he was never allowed to take it off. Then she killed herself and he disappeared.

The police said he’d likely run away. That someone would find him and he’d end up in foster care. No one searched for him, not for very long anyway.

The second thing that happened was that people quit dying. No one noticed at first. There was no way to identify the exact time that it started. But as the hospitals filled up with people fallen into mysterious comas, the media finally began investigating. What they found was that the phenomena went far beyond our small, midwestern city. In rural areas, urban areas, third world countries…everywhere civilization existed, no one was dying. Not just a single day with no deaths—which would have been unheard of in the first place—but days, then weeks, then months…

According to speculation from scientists and news commentators, the people who were falling into comas were the ones who were actually supposed to die. The reason for this theory was that most of the people were either of advanced age or victims of prolonged illness or random events like heart attacks. It was as though they’d marched right up to the precipice of death and for some reason failed to take the final plunge. One man in my town was hit by a train. His body completely shattered. They peeled him off the front of the train, put him on a gurney, and took him to the hospital because his heart was still beating.

Naturally, as time wore on, scientists began experimenting with euthanasia, particularly for people like the train-wreck guy. There was nothing they could do to stop the heart from beating beyond removing the heart altogether. They did so. The bodies they experimented with failed to show any signs of death or decay. It defied all laws of nature. No matter what the scientists tried, the flesh of the not-quite-dead remained vital.

The masses of the comatose began to pile up. There was a great and ongoing debate about whether the bodies still contained souls and whether it was morally righteous to go ahead and bury or cremate them. People started revising their advanced directives to reflect their preferences should they fall into a death coma, as it was popularly called. For the very rich, mausoleums came back into fashion. A religious movement also arose in favor of the mausoleums. They believed there would be some sort of Great Awakening, that the dead would be resurrected, and therefore the dead should be preserved. Of course, not many people wanted to bury the almost-dead. Though they might be able to come to terms with the idea that their loved one was gone, the thought of them in the ground, surrounded by dirt, still alive on a technicality…it was too close to a nightmare. Cremation became the preferred method of disposal. Some viewed it as mercy killing. Mostly it was just plain practical. Given the increased demand, it was also a good job market, which is why I applied for an apprenticeship when I turned eighteen.

I had had a scare, earlier in my youth. My brother, who’d been my caregiver since I was eight, suddenly started having seizures. He was still having them by the time the ambulance arrived. In the emergency room when he finally stopped seizing, he stayed unconscious for over an hour. It took a while before they got him hooked up to a brain scanner. In those minutes, I feared the worst—that my brother had fallen into a death coma.

When the machine showed brain activity, and when he finally awoke, I wept. Later, I questioned myself and my fear. I didn’t want to live like that. I wasn’t naive enough to think I could do something to change the world I lived in. It’s shocking how quickly humanity can adapt to a change, how rapidly something appalling can become the new normal. This was my new normal. And I didn’t want to live in fear of it. I wanted to come to terms with it.

So I took an apprenticeship at a crematorium.

“I’d give anything to go back to the days of pale, livid corpses, blue-lipped and stiff with rigor,” my mentor said one day. He was a slight, aging man with glasses and wispy hair—precisely how a mortician ought to look. “Feels too much like murder, burning such life-like bodies.”

When he first told me that, I figured he was just being poetic. But a few months later, as the police carted him off to the nearest psychiatric hospital, I realized he’d truly felt that way. He’d truly spent his days committing murder after murder after murder…

Maybe it was because I’d never worked with dead bodies before the change, but I adjusted fairly well. After about six months, I’d say I was downright casual about it.

Not long after my twentieth birthday I was shoving a young, bearded hipster into the retort when my ears were pricked by the voice on the radio. My mentor had kept an old turn-dial radio on a table in the corner. After they took him away, I kept it, turning it on every day. It was a part of the world I lived in now.

“The lawsuit could cost billions and cripple the funeral industry,” the radio voice was saying. “A Chicago man’s family was present when he awoke inside the crematorium retort. Fortunately, the man made enough noise to be rescued before the fires could consume him, but he did sustain severe burning in several places. The family is suing the doctors and funeral homes for not recognizing the true nature of the man’s coma. More details coming soon.”

At first, it was just a story. But as the day wore on, the story blew up into a full-fledged scandal and investigation. It was no surprise when, a week later, I was laid off.

My brother, Tyler, lived in the same house he’d raised me in. Nearly forty, he still hadn’t settled down. But at the moment, he had a live-in girlfriend named Annie. I liked her. She was cheerful and seemed to enjoy baking cookies.

Tyler hadn’t changed my bedroom. “Always figured you should have a place to stay when you come visit,” he said, as though he was my father, not my brother.

I watched as he sat my suitcases at the foot of my bed, then I hugged him. “Thank you.”

“Stay as long as you want.”

Annie made us dinner. Since Tyler seemed close-lipped and nearly rude to the poor woman, I did what I could to show extra gratitude for all her work.

That night I left Tyler in the living room watching baseball and ignoring poor Annie, and I went to bed. One of the reasons I’d known Kord, the little boy who’d vanished so long ago, was that our bedroom windows were right across from each other. We would open them and whisper to each other in the night.

I opened my window, turned out my light, and climbed between the cool sheets. A breeze came through the window. I lay on my side and stared at the blackness beyond it. As my eyes adjusted, the outline of his bedroom window formed like a deep blue shadow. I’d seen the house upon my arrival. No one had ever bought it. It sat there empty for ten years.

Strange thing was, it looked exactly the same. See, houses are meant to be lived in. And when they go a long period of time without someone living in them, they tend to start falling apart. Like decay after death. Once the soul departs, the body rots. Or at least it used to. But this house looked healthy. Almost untouched. As far as I’d seen, there weren’t even any cobwebs on the porch rails.

The longer I stared at the window, the more I thought about that boy. We’d talked about everything kids talk about. Ninja Turtles. Batman. Parents. Death. Never once did I enter his house. Never once did he enter mine. But we were as close as two people could be who had never touched. I could almost hear his voice on the breeze blowing in the window.

“Brenna,” he would whisper. “Can you come play?” I’d climb out my window. He’d put toy soldiers on his window sill and we’d play.

I closed my eyes, remembering his voice, remembering how I felt with him. You never really get over your first best friend.

Brenna.

My eyes snapped open. It was just the breeze and my imagination, of course. But the voice wasn’t that of a little boy. It was deep and masculine. I must have conjured it.

I tugged the sheet up under my chin and breathed through my nose. My dozing was fitful. Nightmares waited for me every time I closed my eyes. By three in the morning, I couldn’t take it. I swung my legs over the edge of the bed and went to the window to close it. But instead of slamming closed, the bottom edge of the frame nesting into the sill, it jammed on something…something that prevented it from closing all the way. I slammed it harder before I realized I needed to remove the obstacle. I lifted the window and reached blindly into the sill. My fingers enclosed upon something cold, thin, and a few inches long.

I lifted it. Moonlight glinted off of it. A key. I moved it into the shaft of moonlight slicing through my window. It was glass…a sturdy glass if it could withstand having a window slammed on it twice in a row. I had to squint to make out the detail, but it appeared to have an etching on the handle. A skeleton.

I stared at it for the longest time. “Where did you come from?” I whispered.

Brenna.

I slammed the window shut, ran to my bed, threw the covers over my head and shivered.