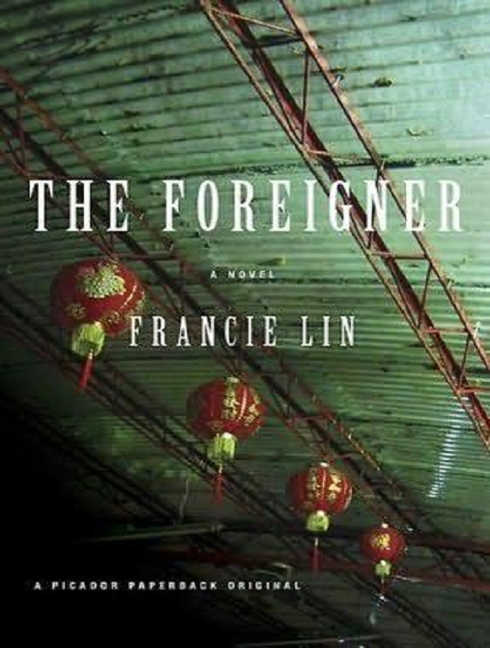

The Foreigner

Authors: Francie Lin

Winner of the Edgar® Award for Best First Novel by an American Author

Set against the Taiwanese criminal underworld,

The Foreigner

is Francie Lin’s audacious debut novel. A noirish tale about family, fraternity, conscience, and the curious gulf between a man’s culture and his deepest self.

Emerson Chang is a mild mannered bachelor on the cusp of forty, a financial analyst in a neatly pressed suit, a child of Taiwanese immigrants who doesn’t speak a word of Chinese, and, well, a virgin. His only real family is his mother, whose subtle manipulations have kept him close—all in the name of preserving an obscure idea of family and culture.

But when his mother suddenly dies, Emerson sets out for Taipei to scatter her ashes, and to convey a surprising inheritance to his younger brother, Little P. Now enmeshed in the Taiwanese criminal underworld, Little P seems to be running some very shady business out of his uncle’s karaoke bar, and he conceals a secret—a crime that has not only severed him from his family, but may have annihilated his conscience. Hoping to appease both the living and the dead, Emerson isn’t about to give up the inheritance until he uncovers Little P’s past, and saves what is left of his family.

The Foreigner

is a darkly comic tale of crime and contrition, and a riveting story about what it means to be a foreigner—even in one’s own family.

THE FOREIGNER

THE FOREIGNERA Novel by

Francie Lin

by Francie Lin

eISBN: 978-1-4299-3863-1

The Duke of She said to Confucius: Where I live, there is an upright man named Gong. When his father stole a sheep, the son spoke out against him.

To which Confucius replied: In my state, the son would protect his father, and the father would protect the son. That is what

we

call righteousness.

—

FROM CONFUCIUS,

The Analects

, 13:18

I

T WAS MY BIRTHDAY,

my fortieth year. I am not a sentimental man, and my birthdays have always passed quietly, with a minimum of anguish and fuss, but for some reason, this year, a sense of dejection hung in my chest like a fog as I drove eastbound across the Bay Bridge to meet my mother for dinner. Rain lashed the windshield. A truck had overturned just past the 880 exit, encircled by flares. Farther on, a dog had been run over, the mangled carcass pulled off to the side and left with its golden fur matted and damp. All these things—melancholy, rain, a little accident, a little blood—all of them are, in hindsight, nothing: souvenirs of a happier time. But back then they seemed to me portentous. Maybe they were.

The Jade Pavilion reservation was for 8:00, and the dashboard clock said 7:52. The traffic budged forward. "Come on. Come

on

." My mother hated to be kept waiting; tardiness was the unforgivable sin. I hadn’t been late for dinner more than three or four times—respectable, considering that we had had dinner every Friday for fifteen years, with few exceptions. Dinner, usually followed by an overnight stay in my old childhood room, with a Hershey’s bar and a nip of whiskey to settle my dreams. I am being unnecessarily poetic here, for my dreams don’t need settling. When I was younger, I used to dream of palaces and kingships, and the sight of an enemy flotilla from the turret of a well-defended fort, but now, more often, I dream that I get up, have my breakfast, and take the Powell-Mason streetcar to my office downtown. My dreams and my reality are more or less the same, and I like the regularity and implied balance.

I was bothered, then, when I arrived at the restaurant late and breathless, and found the place nearly empty, my mother nowhere to be seen.

"You want to sit down?" asked the hostess, snapping her gum. Full-blown orange peonies bloomed in her dark hair.

"No, I’ll wait outside." I tried not to stare at her. The flowers reminded me of the sweet, tangled sleep I used to have, full of a woman and damp sheets and sunset light spilling all over the floor. The starched white collar of her uniform framed a tender little hollow in her throat, where she fingered a string of milky glass beads.

"I’ll… I’ll wait outside."

The restaurant was tucked into an elbow of a huge strip mall. Out in the mall concourse, I called my mother several times, but only got the reservations service. She owned a motel, the Remada Inn, where she had raised both my brother, Little P, and me. The name "Remada" was an inspired bit of trickery on her part, as people tended to mistake ours for the Ramada Inn, yet the misspelling protected us from charges of fraud. Not that the motel had too much business in any case; it was not convenient to the airport, and the customers were mostly long-term tenants stuck in various states of financial or emotional decline.

My mother despised them all. She had arrived in the United States from Taiwan about forty-five years ago, but in that time she hadn’t assimilated so much as grown a prickly, protective shell. Some immigrants were confused or frightened by their dislocation in America, but she tended to see her difference as a mark of the elect. "Americans!" she would say darkly when she heard reports of some social aberration like divorce or pedophilia. She prided herself on speaking very correct English without any slang, but her grasp of detailed grammar and connotations was slippery. In her private grammar,

American

was an epithet with dark, obscure associations, like bottom-feeders glimpsed in the depths of a dirty lake. "Those Americans." "That American."

Those

and

that

deployed like tiny bombs, her scorn and contempt decimating the weak, the dreamy, the lazy, the undecided and naïve—everything she associated with America, with Americans. Divorce, alcoholism, teen pregnancy, unemployment: these, she thought, were the provenance of weak American standards, of a long compromise between comfort and immortality.

Eight-fifteen, eight-twenty. I dialed my mother again: no answer. She had been determined that Little P and I should not be absorbed into the general culture, and accordingly, our childhoods had been strictly regimented, full of paranoia and dour regulations that seemed arbitrary to me now, though at the time I believed that there was some kind of system beneath her injunctions. We were not, for instance, allowed to wear shorts, jean jackets, baseball caps, or thin leather ties, nor were we allowed to stand on outdoor benches or decorative rocks, or the retaining walls of gardens in the park. Soda had to be sipped through a straw and could not be drunk while standing or walking. No girls. Certainly no boys. She had been obsessive about hygiene also, and well into our teens we had to submit to a full inspection of our nethers, back to front. On restless, unhappy nights I can still see the thinning part of her hair as I stand naked on the motel toilet lid, looking down at her probing my dickson clinically with a cotton swab dipped in alcohol.

Eight-twenty-five, eight-thirty. A small, mouse-haired Chinese woman with enormous glasses sat opposite me, finger-dipping into her change purse. She wore a shapeless gray skirt, and her pale, moon-shaped face was framed by thin, wistful plaits. About my age. A nice girl. An accountant, probably. Eight-thirty-five, eight-forty. I crossed my arms and tried to imagine taking her to the Metronome. Under dimmed lights, on the wide parquet, with the broad strokes of a waltz sweeping through the hall, perhaps I could love a woman like this. She didn’t look coordinated, but she might be good at the cha-cha at least. Coins spilled from her pocketbook onto the floor; she got down awkwardly on all fours to retrieve them. Perhaps just a waltz then.

The tip of an umbrella planted itself near my foot.

"Hello, Mother."

She had come steaming up the concourse looking fierce, draped in an old blue silk dress and wielding her umbrella like a majorette’s baton. I was touched to see that she had put on makeup for the occasion, although her mouth was like a hard little knot in her face, her eyebrows sketched on at an angle of permanent displeasure.

"Hair!" she said, pointing the umbrella at my head.

"I didn’t have time to comb it."

She took a tiny brush from her purse.

"Mother!" I ducked, backing away. "Nobody is even looking at me."

"Doesn’t matter." The brush hovered and jabbed. "Don’t you want to look nice for yourself?"

"Mother—"

We regarded each other silently for a moment, with the old, familiar suspicion and appraisal, so deep and habitual that they were, for us, a kind of love. Up close, the makeup made her look rather hollow and aged. I was wearing the shoes she’d given me as a birthday present, an expensive pair of soft suede Ferragamos, and their rich, understated luster stood in sad distinction to her frayed silk and battered handbag. Defeated, I bent my head and allowed her to groom me with quick, fastidious little licks of the brush, a bit of spit wetting down the hairs.

"Was there a problem at the motel?"

"Police!" she said with relish. "Raid! That guy, that Room 210, he is

parolee

from the north. Oregon. They track him down, they come to take him away. You know I like fairness, so at first I say no way! Are you kidding? You cannot just take my customer away like that! But then I check my book." Her mouth crimped down in a little caret. "He have already paid up front for a week in cash. So take him, I say! Room 210. Here is the key. Not my affair." She gave a little moo of satisfaction and clicked her tongue, making a sound like faint applause.

The mousy woman had brightened when my mother appeared, sitting up straighter and adjusting her plastic frames attentively, and my mother now hailed her.

"Mei Hua! I am glad you could come." She held out her hand to the girl.

"Mother—"

"Just a friend, Emerson," she said casually, as she commandeered Mei Hua and steered her toward the restaurant. "I invite her at the last minute. What is a birthday without friends?"

"But I only made a reservation for two."

She gave me a restrained but significant look. My mother wanted me to get married. This desire had consumed her for so long that it had ceased to be meaningful and was nurtured now with franticness, like a tire spinning uselessly in the snow. Over the years, she had presented me, humiliatingly, to a range of women she found appropriate—all Chinese or Chinese-American, though with variants: tall, fat, myopic, depressed—who appraised me with gimlet hardness behind their demure, almondlike eyes; you could hear pension and interest calculations being totted up in their heads. My mother herself had entered marriage purely as a matter of ritual and practicality. "Love!" she would say dismissively.

"Mother," I repeated.

She gave me a dazzling smile full of teeth and breezed into the Jade Pavilion.

We clustered ourselves at one end of the huge round table, my mother sitting between the woman and me as if to broker the peace. In stony silence the three of us studied the menu, though this was only a formality, since my mother always did the ordering. She summoned the waitress with an impatient snap of the fingers, as one would call a dog, and when she had finished ordering and had wiped all the dinnerware pointedly with her napkin—she thought the Cantonese were dirty—she pinched me under the table.

"Talk," she mouthed, her brows melting a little with the force of disapproval. I looked over at the woman. The plaits, the dull, round face. Eyes magnified alarmingly by the glasses. She had a weak, tremulous smile, and I saw that she had worn what was probably her nicest blouse. The obvious care she had taken with her appearance made me sad, and also enraged: I would have to be kind.