The Fry Chronicles (24 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

The Footlights clubroom was a long, low room under the Union chamber and had a small stage with a lighting rig and a piano at one end and a sort of bar at the other. All along the walls hung framed posters of past revues and photographs of past Footlighters. In their duffel coats, black polo necks, tweed jackets or wind-cheaters, with studious black-rimmed spectacles perched on their noses and untipped cigarettes between their lips, they all seemed so much older than we were, so much cleverer, so much more talented and a world more sophisticated. They looked more like French left-bank intellectuals or avant-garde jazz musicians than members of a student comedy troupe. Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller, Bill Oddie, Graeme Garden, John Cleese, David Frost, John Bird, John Fortune, Eleanor Bron, Miriam Margolyes, Douglas Adams, Germaine Greer, Clive James, Jonathan Lynn, Tim Brooke-Taylor, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman, Griff Rhys Jones, Clive Anderson …

‘The tradition stops here,’ Hugh and I would mutter as we looked up for inspiration and found our gaze meeting theirs. Such a tradition, such a rich history as the Footlights’, was in part inspiration and encouragement but in part insurmountable obstacle and impossible burden.

Neither Hugh nor I seriously thought for a moment that we would have a career in comedy or drama or any other branch of showbusiness. I would, if I scraped a First

in my Finals, probably stay on at Cambridge, prepare a doctoral thesis and see what I could offer the academic world. I hoped, in my innermost secret places, that I might be able to write plays and books on top, under, or to one side of, whatever tenured university post might come my way. Hugh claimed that he had set his eyes on the Hong Kong police force. There had been one or two corruption scandals in the Crown Colony, and I think he rather fancied the image of himself as a kind of Serpico figure in sharply creased white shorts, a lone honest cop doing a dirty, dirty job … Emma, none of us doubted, would go out and achieve her destiny in world stardom. She already had an agent. A forbiddingly impressive figure called Richard Armitage, who drove a Bentley, smoked cigars and sported an old Etonian tie, had signed her on to the books of his company, Noel Gay Artists. He also represented Rowan Atkinson. Emma’s future was certain.

None of which is to say that Hugh and I lacked ambition. We were ambitious in the peculiar negative mode in which we specialized: ambitious not to make fools of ourselves. Ambitious not to be called the worst Footlights show for years. Ambitious not to be mocked or traduced in the college and university newspapers. Ambitious not to look as if we thought ourselves pro-ey showbizzy stars. Ambitious not to fail.

Within two weeks of meeting we finished the

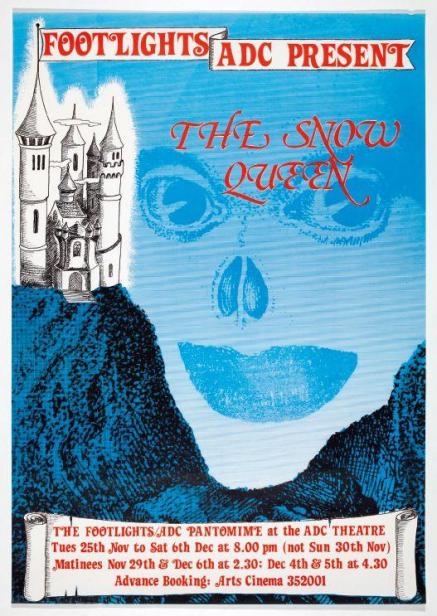

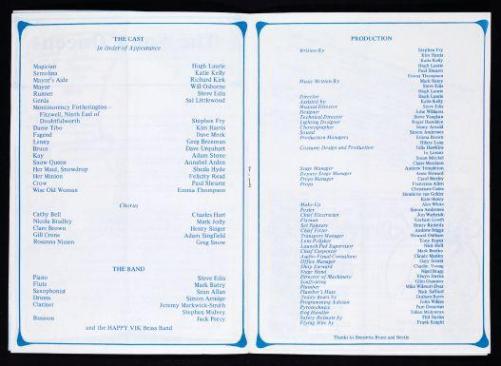

Snow Queen

script. I also wrote a monologue with Emma for her appearance as a mad, unpleasant and foul-smelling Wise Old Woman. Katie was cast as the heroine, Gerda, while Kim, ascending to the role of Pantomime Dame as if born to it, played her strikingly Les Dawson-like mother. I was a silly-ass Englishman called Montmorency Fotherington-Fitzwell,

Ninth Earl of Doubtful, who by happy chance never sang. Australian-born Adam Stone from St Catharine’s played Kay, Gerda’s boyfriend, Annabelle Arden had the title role of the Snow Queen herself and an extremely funny first-year called Paul Simpkin played a kind of dumpling-faced jester. There was a talented young man called Charles Hart, whom we put in the chorus. He later came to fame and frankly not inconsiderable fortune as the lyricist for Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s

Phantom of the Opera

and

Aspects of Love

. Greg Snow, a howlingly funny friend from Corpus Christi, was in the chorus too, alternately amusing and exasperating Hugh with his astounding camp and a talent for bitchery that approached high art.

Hugh had a hand in the music, and I had a finger or two in the lyrics but most of the composition and arrangements were the work of an undergraduate called Steve Edis, whose girlfriend, Cathie Bell, danced and sang in the chorus like a demented can-can girl, despite her devastating susceptibility to severe asthma attacks.

The Snow Queen

, 1980. My first Footlights appearance.

The pantomime seemed to go well, and by the time the Lent term came Hugh and I were already starting to write material for the Late Night Review, to which Hugh had given the title

Memoirs of a Fox

. It irked him that no one seemed to get the reference, but it was a fine enough title without having to know Siegfried Sassoon. Titles, you soon discover, are fantastically irrelevant. You could call it, as American Indians were said to do of their babies, the first thing you see out of the window: Running Bull, Long Cloud or Parked Cars. You could even call it ‘The First Thing You See Out of the Window’. Actually, I quite like that. One afternoon I found a tattered old exercise book in the Footlights Clubroom. Scrawled on the cover were the words: ‘May

Week Revue Title Suggestions’. Over generations members had written down ideas for titles for shows. My favourite was Captain Fellatio Hornblower. I always suspected this to be the handiwork of a young Eric Idle. Many years later I asked him; he had no memory of it but agreed that it sounded pretty much his style and was willing to take the credit especially if there was a royalty in it for him.

More or less opposite Caius College stood a restaurant called the Whim. For generations this friendly, un-pretentious establishment had been a favourite student haunt for good cheap suppers and long, lazy Sunday brunches. One day, quite unexpectedly, it closed down and covered itself in scaffolding. Two weeks later it reopened as something I had never seen or experienced before: a fast-food burger bar. Still called the Whim, it was now the home of the new Whimbo Burger, two beef patties smothered in a slightly tangy, slightly sweet creamy sauce, topped with slices of gherkin, slapped into a triple decking of sesame seed bunnage and presented on a styrofoam tray to the accompaniment of chips called ‘fries’ and whipped-up ice-cream called ‘milkshakes’. The tills had pre-set buttons on them that allowed the perkily paper-capped assistants to press a button for Whimbo, say, and another for milkshake or fries, and all the prices would be automatically registered and calculated. It was like entering an alien space-ship, and I am sorry to say that I loved it to distraction.

A ritual was established. Hugh, Katie, Kim and I, after spending much of the afternoon in A2 playing chess, talking and smoking, would leave Queens’, walk along King’s Parade to Trinity Street and into the Whim, then on to the Footlights clubroom, cheerfully swinging our catch, two carrier bags crammed with steaming Whimmery. I

could happily manage two Whimbos, a regular order of fries and a banana milkshake. Hugh’s standard intake was three Whimbos, two large orders of fries, a chocolate milkshake and whatever Katie and Kim, who were more delicate, had failed to finish. His years of rowing and the enormously high calorific output they had demanded of him had given Hugh a colossal appetite and a speed of ingestion that to this day stagger all who witness them. I do not exaggerate when I say that he can eat a whole 24-ounce steak in the time it would take me, a much faster than average eater myself, to cut and swallow two mouthfuls. When he returned from his daily river work during his Boat Race year, Katie would cook just for him a cottage pie to a recipe for six people on which she would place four fried eggs. He would polish this off before she had a chance to make a dent in her own soup and salad.

I was rather fascinated by the levels of fitness Hugh had attained for the Boat Race. It is much, much longer than a standard regatta course and requires enormous stamina, strength and will to complete.

‘At least while you were regularly rehearsing for it,’ I remember saying to him once, ‘you must have gloried in the feeling of being so fit.’

‘Mm,’ said Hugh, ‘pausing only to point out that we prefer the word “training” to “rehearsing”, I have to tell you that the fact is you never really feel fit at all. You train so hard you are constantly in a dopey state of numb torpor. On the river you slap and sting yourself into action and heave to, but when that’s over you’re torpid again. In fact the whole thing’s pointless bloody agony.’

‘Which is why,’ I said, ‘it is best left to convicts and galley slaves.’

For all that, how proud I would be if I had ever done something so extraordinarily demanding, so appallingly hard, so wildly extreme as train and row in the Boat Race.

In the clubroom, after the last traces of Whimbo and milkshake had been dealt with, Hugh would play at the piano, and I would watch him, with a further mixture of admiration and envy. He is one of those people with the kind of faultless ear for music that allows him to play anything, fully and properly harmonized, without sight of a score. In fact he cannot really read music. The guitar, the piano, the mouth organ, the saxophone, the drums – I have heard him play them all and I have heard him singing with a blues voice that I would sacrifice my legs to have. It ought to be most annoying, but in fact I am insanely proud.

It is a matter of extreme good fortune that, handsome as Hugh is, prodigiously gifted as he is, funny and charming and clever as he is, I have never felt an erotic stirring for him. How catastrophic, how painfully embarrassing that would have been, how disastrous for my happiness, his comfort and any future we might have had together as comedy collaborators. Instead our instant regard and liking for each other developed into a deep, rich and perfect mutual love that the past thirty years has only strengthened. The best and wisest man I have ever known, as Watson writes of Holmes. I shall stop before I get all teary and stupid.

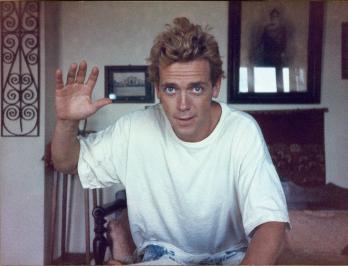

Hugh in Crete. We rented a villa for the purposes of writing comedy.

A cretin in a Cretan setting.