The Fry Chronicles (23 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

‘Coo.’

‘Yes, and he needs someone to write sketches with. He wants me to bring you over to his rooms at Selwyn.’

‘Me? But I don’t know him … how … what?’

‘Yes you do!’ She flung two cushions in succession. ‘I introduced you at Edinburgh.’

‘You did?’

There were no cushions left so she flung me a speaking glance instead. Possibly the speakingest glance that had been flung in Cambridge that year. ‘For someone with such a good memory,’ she said, ‘you have a terrible memory.’

Kim, Emma and I walked up Sidgwick Avenue towards Selwyn College. It was a cold November night, and the air held a smell of gunpowder from a Bonfire Night party being held somewhere near the Fen Causeway. We came to a Victorian building on the rugby-ground side of Grange Road, not far from Cambridge’s newest college, Robinson.

Emma led us through the open street door and up some

stairs. She knocked on a door at the end of the corridor. A voice grunted for us to enter.

He was sitting on the edge of his bed, a guitar on his knee. At the other side of the room was his girlfriend, Katie Kelly, whom I knew slightly. Like Emma, she read English at Newnham. She was very pretty and had long blonde hair and a ravishing smile.

He stood awkwardly, the red flags of his cheeks more pronounced than ever. ‘Hullo,’ he said.

‘Hullo,’ I said.

We were both people who said ‘hullo’ rather than ‘hello’.

‘Red wine or white?’ said Katie.

‘I’ve been writing a song,’ he said and started to strum on his guitar. The song was a kind of ballad sung in the character of an American IRA supporter.

Give money to an IRA bomber?

Why, yessir, I’d consider it an honour,

Everybody must have a cause.

The accent was flawless and the singing superb. It seemed to me a perfect song.

‘Woolworths,’ he said as he laid the instrument down. ‘I borrow guitars that cost ten times as much, but they just don’t do it for me.’

Katie approached with the wine. ‘Well, are you going to tell him?’

‘Ah. Yes. Well, thing is. Footlights. I’m the President, you see.’

‘I saw you in

Nightcap

you were magnificent it was brilliant,’ I said in a rush.

‘Oh. Gosh. Well. No. Really? Well, er …

Latin!

Top. Absolutely top.’

‘Nonsense, oh shush.’

‘Completely.’

The excruciating horror of mutual admiration out of the way, we both paused, unsure of how to continue.

‘Well, go on,’ said Emma.

‘Yes. So. There are two Smokers left this term, but most importantly there’s the panto.’

‘The panto?’

‘Yup. The Footlights pantomime. Two years ago we did

Aladdin

.’

‘Hugh was the Emperor of China,’ Katie said.

‘I missed that, I’m afraid,’ I said.

‘Quite right. I would have too. If I hadn’t been in it. Anyway, this year we’re doing

The Snow Queen

.’

‘Hans Christian Andersen?’

‘Yup. Katie and I have been writing it. We’ve got this …’ he showed me some script.

Five minutes later Hugh and I were writing a scene together as if we had been doing it all our lives.

You read about people falling suddenly in love, about romantic thunderbolts that go with clashing cymbals, high quivering strings and resounding chords and you read about eyes that meet across the room to the thudding twang of Cupid’s bow, but it is less often that you read about collaborative love at first sight, about people who instantly discover that they were born to work together or born to be natural and perfect friends.

The moment Hugh Laurie and I started to exchange ideas it was starkly and most wonderfully clear that we shared absolutely the same sense of what was funny and the same scruples, tastes and sensitivities as to what we found derivative, cheap, obvious or stylistically unacceptable. Which is not to say that we were similar. If the world is full of plugs looking for sockets and sockets looking for plugs, as – roughly speaking – the Platonic allegory of love suggests, then there is no doubt we did seem each to possess precisely the qualities and deficiencies the other most lacked. Hugh had music where I had none. He had an ability to be likeably daft and clownish. He moved, tumbled and leapt like an athlete. He had authority, presence and dignity. I had … hang on, what

did

I have? Patter and fluency, I suppose. Verbal dexterity. Learning. Hugh always said that I also added what he called

gravitas

to the proceedings. Although he had great authority himself on stage I suppose I had the edge on playing older authority figures. I wrote too. I mean I actually physically wrote lines down with pen and paper or typewriter. Hugh kept the phrases and shapes of the monologues and songs he was working on in his head and only wrote them down or dictated them when a script was needed for stage-management or administrative purposes.

Hugh was determined that the Footlights should look grown-up but never pleased with itself or, God forbid, cool. We both shared a horror of cool. To wear sunglasses when it wasn’t sunny, to look pained and troubled and emotionally raw, to pull that sneery snorty ‘Er?!!

What

?!’ face at things that you didn’t understand or from which you thought it stylish to distance yourself. Any such arid, self-regarding stylistic narcissism we detested. Better to look a naive simpleton than jaded, tired or world-weary, we felt. ‘We’re

students

, for fuck’s sake,’ was our credo. ‘We have people making our beds and tidying our rooms for us. We live in panelled medieval rooms. We have theatres, printing presses, first-class cricket pitches, a river, boats, libraries and all the time in the world for contentment, pleasure and fun. What right have we got to moan and moon and mooch about the place looking tortured?’

We were fortunate that the age of young people doing stand-up comedy hadn’t yet arrived. The idea, and I am afraid it has since become a reality, of pained emo students leaning listless and misunderstood on a mike-stand railing against the burden of life would be more than either of us would have been able to bear. We were exceptionally attuned to pretension, aesthetic discord and hypocrisy. The young are so priggish. I hope we are much more tolerant now.

Almost no one we ever worked with either at Cambridge or afterwards quite seemed to share or even understand our aesthetic, if I can dignify it with such a word. It is probable that our fear of being unoriginal, of looking cocky, of being obvious or of being seen ever to have chosen the line of least resistance caused us difficulty in our comedy careers. The same fears might also have pushed us to some of our best endeavours too, so there is no real reason to regret the sensitivity and fastidiousness that only we appeared to share. We soon became familiar with the expressions of bewilderment that might flicker over the faces of those who suggested something that inadvertently trespassed against our instinctive sense of what could or could not be funny, right or fit. I don’t think we were ever aggressive or unkind, certainly not deliberately, but when two people are absolutely in harness with regard to matters of principle and outlook it must be very alienating to outsiders, and I expect two tall public-school figures like us must have seemed forbidding and aloof. Inside, of course, we felt

anything but. I would not want to paint a picture of us as earnest, dogmatic ideologues, the Frank and Queenie Leavis of Comedy. We spent most of our time laughing. The smallest things would set us off like teenagers, which of course we had only just stopped being.

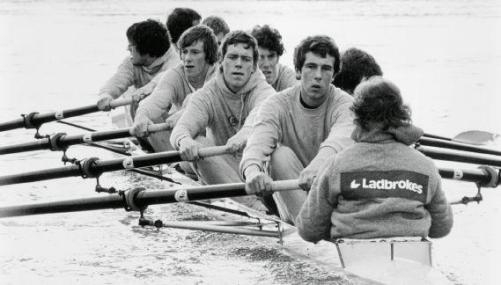

Hugh had come up to Cambridge from Eton College as a successful international youth oarsman, having pulled himself through the water to gold with his schoolfriend James Palmer in the coxless pairs event in the Junior Olympics and at Henley. Back in the thirties his father had been in a winning Cambridge Blue boat for each of his three years and went on to row in the British eight at the Berlin Olympics of 1936 and again in the coxless pairs in the 1948 London games, where he and his partner Jack Wilson won gold. Had glandular fever not struck, Hugh would certainly have rowed for the university straight away but, denied by his illness a seat in the Blue boat for his first year, he looked about for something else to do and found himself cast in

Aladdin

and then, two terms later,

Nightcap

. In his second year he abandoned the Footlights and did what he had come to Cambridge to do, pull that rowing-boat through the water. On the river by five or six in the morning, hours of backbreaking rowing, then road work, gym work and more time on the river. He got his Blue in the 1980 boat race, which Oxford won by a canvas, the closest result there had ever been. You can imagine the disappointment. How many times he must have revisited every yard of that race in his head. Upping the stroke rate by one beat a minute, just one neater piece of steering on the bend, 2 per cent more effort at Hammersmith … it must have been heartbreaking to have come so close. I tried to tell him that my own experience of losing to Merton in

the final of

University Challenge

meant that I knew exactly how he felt. The look he gave me could have stripped the flesh from a rhinoceros.

Unable to afford an outboard motor, Hugh Laurie and his poor dear friends are having to propel themselves through the water.

The following year, his last, he could either stay with rowing or return to the Footlights, but he could not do both. President of the Cambridge University Rowing Club, or President of the Cambridge Footlights? He claims that he tossed a coin and it came down Footlights. He had gone to Edinburgh and seen

Latin!

and decided that perhaps I might be a useful new recruit to his Footlights. Only he and Emma were left from the first year and he needed fresh blood. Kim was co-opted on to the committee as Junior Treasurer, Katie was Secretary, Emma Vice-President and a computer scientist from St John’s called Paul Shearer, a funny, lugubrious performer with eyes almost as big as Hugh’s, was already on board as Club Falconer. This strange office went back to the days when the Footlights were quartered in Falcon Yard. I don’t believe there were any duties attached to being Falconer, but it looked good, and I envied Paul’s title sorely and reprehensibly.

There is perhaps one overriding reason why the Footlights has produced such an astonishing number of figures who have gone on to make their mark in the world, and that reason is continuity. The Footlights has a tradition which goes back over a hundred years. That tradition inspires many with a comic itch to choose Cambridge as their university. The Footlights has a regular schedule: a pantomime in the Michaelmas Term, a Late Night Revue at the ADC in the Lent Term and the May Week Revue at the Arts Theatre, which then goes on to tour Oxford and other towns before arriving in Edinburgh for the Fringe Festival in August. And throughout that year are peppered Smokers. The word is an abbreviation of Smoking Concert. I dare say smoking is no longer permitted at these public events, but the name has stayed. In our time Smokers took place in the clubroom. The fact that the club had its own little venue was another of the inestimable advantages held by the Footlights over comedy groups in other universities.

The closest equivalent to a Smoker in the outside world is an open-mike evening I suppose, although in our day there was a small filtration system in place, so ‘open’ isn’t quite the word. Anyone from any college with hopeful sketches, quickies, songs or monologues would come to the clubroom the day before the Smoker and exhibit their material on the stage. Whichever committee member was running that Smoker would yay or nay them. If a yay, their piece would be added to the running order: the auditions would go on until there was enough there for an evening’s entertainment. The huge advantage of this system was that by the time the May Week Revue came around there was a lot of material to choose from and plenty of performers to pick, all of them having been tried out in front of an audience. In most other universities they don’t have that kind of feeder system. Josh and Mary at Warwick or Sussex might say, ‘Hey, we’re funny, let’s write a show and take it to Edinburgh! We’ll put Nick and Simon and Bernice and Louisa in it, and Baz can write the songs.’ They are probably all very funny and talented people, but they won’t have the year’s worth of practice and experience and the cupboard full of proven material that a Footlights show can call upon. That in essence, I believe, is why year after year the club continues to do so well. It is why their tours always sell out and why young people with a feel for comedy are so often disposed to put a tick next to Cambridge in the university application form.