The Fry Chronicles (27 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

‘Do you see yourselves,’ he asked us afterwards, ‘doing this kind of thing professionally? As a career?’

It was all so sudden, strange and overwhelming. A few terms earlier I had been happy to wander on as a grizzled soldier or warty old king in productions of Chekhov and Shakespeare. I had listened to the more serious actors talking about applying for places on the Webber Douglas Academy graduate course, the path that Ian McKellen

had taken after Cambridge. Since I had met Hugh and started writing sketches with him and on my own I had dared hope that I might perhaps apply one day to BBC radio for a job as a scriptwriter or assistant producer or something along those lines. About my future as a comic performer I was less sure, however. All the facial mastery, double-takes, clowning and fearless assurance that Hugh and Emma displayed on stage and in rehearsal came much less naturally to me. I was voice and words; my face and my body were still a source of shame, insecurity and self-consciousness. That this Richard Armitage was prepared, keen even, to take me on and shepherd me into a genuine career seemed like astonishingly good luck.

I later discovered that, crafty old fox that he was, Richard had sent his youngest client ahead to see us and deliver his opinion. Which explained what Rowan had been doing there. Plainly he had made encouraging enough noises about us for Richard himself to make the journey to Cambridge and, now that he had seen the show for himself, to make this offer.

I accepted, of course. As did Hugh and Paul.

‘Of course,’ Hugh said, walking back from the theatre afterwards, ‘it doesn’t necessarily mean anything. He probably scoops up dozens every year.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘But still, I’ve got an agent!’

I stopped to break the news to a parking meter. ‘I’ve got an agent!’

The silhouette of King’s College chapel loomed up against the night sky. ‘I’ve got an agent!’ I told it. It was unmoved.

My last May Ball, my last Cherubs Summer Party on the Grove at Queens’. May Week parties all over Cambridge, new levels of drunkenness, mooning, stumbling about, weeping and vomiting. Kim and I threw our own party on the Scholars’ Lawn of St John’s and got through every last case and bottle of Taittinger that Kim’s parents had kindly sent down. My family came to the graduation ceremony: hundreds of identically subfusc graduands-turned-graduates milled about on the lawn outside the Senate House, all looking suddenly rather adult and forlorn as they posed with forced smiles for parental photographs and said their final farewells to three-year friendships. The shadow of the outside world was looming over us all, and that three years seemed suddenly to peel and shrink away like a snake’s sloughed skin, too shrivelled and small ever to have fitted the fine and gleaming years of our ownership.

In room A2, Queens’. Graduation day: posing with sister Jo.

Kim’s parents lived in Manchester but they also had a house in the prosperous London suburb of Hadley Wood, a brisk walk from High Barnet and Cockfosters Tube Stations, and they made this entirely available to Kim and me as soon as we left Cambridge. It was an absurdly wonderful and luxurious introduction to life outside university. On the television there I watched Ian Botham wrench the Ashes from Australia’s grasp and felt like the happiest man in the universe.

Almost immediately

The Cellar Tapes

was off to Oxford for a week at the Playhouse Theatre. After the pleasures of the Cambridge Arts, the Playhouse, with its long, narrow skittle-alley auditorium appeared wholly inimical to comedy, and our material seemed to us to fall

flat. The management and technical staff of the theatre were less than welcoming, and we spent a frightened, unhappy week avoiding the hostile glares of the tab men and lighting crew and alternating between melancholy wails and hysterical laughter as we huddled together for mutual comfort and support. It was a bewildering crash to earth. Hugh was so angered by the staff’s unkindness that he wrote a letter to the manager which he showed me before posting. I had never seen cold fury so expertly rendered into polite but damning prose.

From Oxford we travelled to the theatre at Uppingham School, Chris Richardson welcoming us as two years earlier he had prophesied he would. Oxford had convinced us our show was a shambles and that Edinburgh would be a disaster, but Uppingham rebuilt our morale a little: the staff and school made a supportive and enthusiastic audience and the theatre – on whose boards I had been the very first to step in 1970 as a witch in

Macbeth

†

– was a perfect arena in which to restore our confidence. Christopher was the warmest and most thoughtful host, making sure that we each had excellent accommodation, including a small bottle of malt whisky on the bedside table.

The great William Goldman is famous for saying of Hollywood that ‘nobody knows anything’, an apophthegm that holds just as true in theatre. I received a letter from someone who had been to

The

Cellar Tapes

at the Oxford Playhouse and wanted to tell me that they thought it the best show of its kind they had ever seen. I tried and failed to remember a single moment of the Oxford run that I thought had gone well. I realized, however, if I was honest, that the audience did at least laugh, and there had been sustained and enthusiastic applause at the end.

I suppose the rudeness of the theatre staff and the shape of the auditorium had contrasted so negatively with the perfection of Cambridge that the entire experience seemed black and hopeless.

Before long we arrived at Edinburgh, where we found ourselves sharing St Mary’s Hall with the Oxford Theatre Group, whose own show was on immediately before ours. They were friendly and self-deprecating and charming. St Mary’s was a large venue with temporary seating banked high. It turned out to be perfect for the show. We received favourable reviews and found ourselves sold out for the two weeks of our run.

We performed two sketches on the radio for a BBC Radio 2 Fringe round-up programme presented by Brian Matthew, who interviewed us afterwards. It was my first time on the radio: performing the sketch was fine, but as soon as I had to speak as myself I found my throat restricted, my mouth dry and my brain empty. This would be the case for years to come. Alone in my bedroom I could say things to an imaginary interviewer that were fluent, amusing and assured. The moment the green recording light was on I froze.

One night Richard Armitage left a note to say that someone from the BBC would be present and would like to see us. Two days later he told us to give some time after the show to two people from Granada Television. The following night Martin Bergman, who had been President of Footlights in ’77–’78 and whom I had seen in

Nightcap

,

came to see the show too. They all had offers that made us dizzy with astonishment.

The man from the BBC asked if we might be willing to record

The

Cellar Tapes

for television. The two from Granada, a florid Scot called Sandy and a pert young Englishman call Jon, wondered if we would be interested in developing a comedy sketch show for them. Martin Bergman told us that he was arranging a tour of Australia. September to December, Perth, Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney, Canberra and Brisbane. Did we like the idea?

On the penultimate night of the run, as we were executing our final bows to the audience, their cheering suddenly increased in volume and intensity. This was gratifying but inexplicable. Hugh nudged me; a man had walked on stage from the wings behind us and was coming forward holding his hand up for silence. His presence only encouraged more cheering. It was Rowan Atkinson. For a moment or two I thought he had gone insane. His reputation for timidity was already established. It made no sense whatsoever for him to be here.

‘Um, ladies and gentlemen. Do forgive me for interrupting like this,’ he said. ‘You must think it most odd.’

These innocent remarks elicited greater laughs from the audience than any they had favoured us with all evening. Such is the power of fame, I remember thinking even as I looked on bewildered and intrigued by this peculiar invasion. Of course, Rowan had a way with words like ‘odd’ that did make them very funny.

‘You may know,’ he continued, ‘that this year sees the institution of an award for the best comedy show on

the Edinburgh Fringe. It is sponsored by Perrier … the bubbly water people.’

More laughter. No one can say the word ‘bubbly’ quite like Rowan Atkinson. My heart was beginning to hammer by now. Hugh and I exchanged glances. We had heard of the founding of this Perrier Award and of one thing we were absolutely certain …

‘The organizers and judges of the award, which is to encourage new talent and new trends in comedy, were absolutely certain of one thing,’ Rowan continued, echoing our conviction. ‘That whoever won it wouldn’t be the Cambridge bloody Footlights.’

The audience drummed their feet in appreciation, and I began to fear for the safety of the temporary structure supporting them.

‘However, with a mixture of reluctance and admiration, they unanimously decided that the winner had to be

The Cellar Tapes

…’

The auditorium exploded with applause, and Nica Burns, organizer of the award (after thirty years she still is. Indeed she funded it herself when the sponsorship dried up), stepped forward with the trophy, which Rowan handed to Hugh.

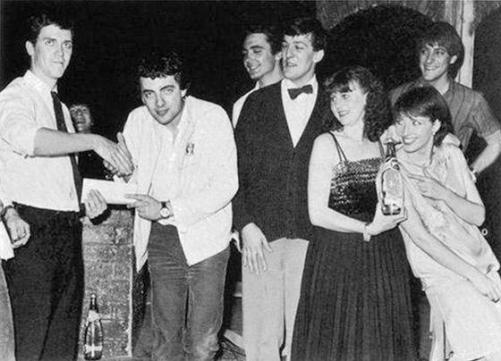

Rowan Atkinson presents Hugh with the Perrier Prize cheque. Edinburgh, 1981.

The Vice-Chancellor placing in my hands a piece of paper that testified to my status as a BA (Hons.) was a small thing compared to this.

We had done it. We had put on a show and we had not disgraced ourselves. Indeed, we seemed to have done better than that.

Later that night, after dinner with Rowan and Nica and the people who looked after Perrier’s PR, we trailed drunkenly home to our digs.

I lay awake almost all the night. I am not romanticizing the moment. I remember how I lay awake and where my thoughts took me.

A year and a half earlier I had been on probation. For almost all of my childhood and youth I had been lost in the dense blackness of an unfriendly forest thick with brambles, treacherous undergrowth and hostile creatures of my own making.

Somewhere, somehow I had seen or been offered a path out and had found myself stumbling into open, sunlit country. That alone would have been pleasure enough after a lifetime’s tripping and tearing myself on ugly roots and cruel thorns, but not only was I in the open, I was on a broad and easy path that seemed to be leading me towards a palace of gold. I had a wonderful, kind and clever partner in love and a wonderful, kind and clever partner in work. The nightmare of the forest seemed a long distance behind me.

I cried and cried until at last I fell asleep.

Enough time has passed for the 1980s to have taken on an agreed identity, colour, style and flavour. Sloane Rangers, big hair, Dire Straits, black smoked-glass tables, unstructured jackets, New Romantics, shoulder pads,

nouvelle cuisine

, Yuppies … we have all seen plenty of television programmes flashing images of all that past our eyes and insisting that this is what the decade meant.

As it happens, resistant to cliché as I try to be, the eighties for me conformed almost exactly to every one of those rather shallow representations. When I was tipped out of Cambridge and into the world in 1981, Ronald Reagan was beginning the sixth month of his presidency, Margaret Thatcher was suffering the indignity of a recession, Brixton and Toxteth were aflame, IRA bombs exploded weekly in London, Bobby Sands was dying on hunger strike, the Liberal and Social Democrat parties had agreed to merge, Arthur Scargill was about to take up the leadership of the National Union of Miners, and Lady Diana Spencer was a month away from marrying the Prince of Wales. None of that seemed especially peculiar at the time, of course, nor did it seem as if one was living a television researcher’s archive package.