The Fry Chronicles (40 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

In those days the house of Light Entertainment was divided into two departments, Comedy and Variety. Sitcoms and sketch shows flew under the Comedy flag and programmes like

The Generation Game

and

The Paul Daniels Magic Show

counted as Variety. The head of Light Entertainment was a jolly, red-faced man who could easily be mistaken for a Butlin’s Redcoat or the model for a beery husband in a McGill seaside postcard. His name was Jim Moir, which also happens to be Vic Reeves’s real name, although at this time, somewhere in 1983, Vic Reeves had yet to make his mark. Hugh and I had first met the executive Jim Moir at the cricket weekend at Stebbing. He had said then, with the assured timing of a Blackpool front-of-curtain comic: ‘Meet the wife, don’t laugh.’

Hugh and I were shown into his office. He sat us down on the sofa opposite his desk and asked if we had comedy plans. Only he wouldn’t have put it as simply as that, he probably said something like: ‘Strip naked and show me your cocks,’ which would have been his way of saying: ‘What would you like to talk about?’ Jim routinely used colourful and perplexing metaphors of a quite staggeringly explicit nature. ‘Let’s jizz on the table, mix up our spunk and smear it all over us,’ might be his way of asking, ‘Shall we work together?’ I had always assumed that he only spoke like that to men, but not so long ago Dawn French and Jennifer Saunders confirmed that he had been quite as eye-watering in his choice of language with them. Ben Elton went on to create, and Mel Smith to play, a fictional head of Light Entertainment based on Jim Moir called Jumbo Whiffy in the sitcom

Filthy Rich & Catflap

. I hope you will not get the wrong impression of Moir from my description of his language. People of his

kind are easy to underestimate, but I never heard anyone who worked with him say a bad word about him. In the past forty years the BBC has had no more shrewd, capable, loyal, honourable and successful executive and certainly none with a more dazzling verbal imagination.

Hugh and I emerged from our meeting stupefied but armed with a commission. John Kilby, who had directed

The Cellar Tapes

, would direct and produce the pilot show that we were now to write. We conceived a series that was to be called

The Crystal Cube

, a mock-serious magazine programme that for each edition would investigate some phenomenon or other: every week we would ‘go through the crystal cube’. Hugh, Emma, Paul Shearer and I were to be the regulars and we would call upon a cast of semi-regular guests to play other parts.

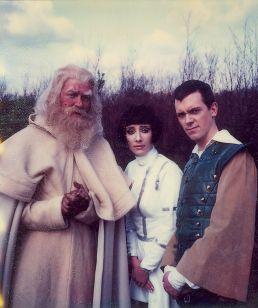

The Crystal Cube

, with Emma and Hugh.

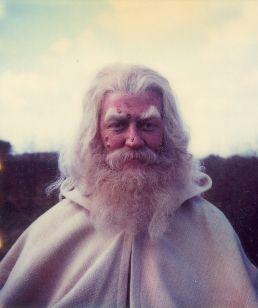

The Crystal Cube.

The warty look was created using Rice Krispies. True story.

Back in Manchester filming

Alfresco

, we began to write in our spare time. Freed from the intimidation of having to match Ben’s freakish fecundity, we produced our script in what was for us short order but would for Ben have constituted an intolerable writer’s block. It was rather good. I feel I can say this as the BBC chose not to commission a series: given that and my archetypical British pride in failure it hardly seems like showing off for me to say that I was pleased with it. It is out there now somewhere on YouTube, as most things are. If you happen to track it down you will find that the first forty seconds are inaudible, but it soon clears up. Aside from technical embarrassments there is also a good deal wrong with it comically, you will note. We are awkward, young and often incompetent, but nonetheless there are some perfectly good ideas in it struggling for light and air. John Savident, now well known for his work in

Coronation

Street

, makes a splendid Bishop of Horley, Arthur Bostrom, who went on to play the bizarrely accented Officer ‘Good moaning’ Crabtree in

’Allo ’Allo!

, guested as an excellently gormless genetic guinea-pig, and Robbie Coltrane was his usual immaculate self in the guise of a preposterously macho film-maker.

If I was disappointed, upset or humiliated by the BBC’s decision not to pick up

The Crystal Cube

, I was too proud to show it. Besides, there were plenty of comedy and odd jobs for me to be getting on with in the meantime. One such was collaborating with Rowan Atkinson on a screenplay for David Puttnam. The idea was an English

Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday

in which Rowan, an innocent abroad, would find himself unwittingly involved in some sort of crime caper. The character was essentially Mr Bean, but ten years too early.

I drove up to stay with Rowan and his girlfriend, Leslie Ash, in between visits to Manchester for the taping of

Alfresco 2

. The house in Oxfordshire was, I have to confess, a dazzling symbol to me of the prizes that comedy could afford. The Aston Martin in the driveway, the wisteria growing up the mellow ashlar walls of the Georgian façade, the cottage in the grounds, the tennis court, the lawns and orchards running down to the river – all this seemed so fantastically grand, so imponderably grown-up and out of reach.

We would sit in the cottage, and I would tap away on the BBC Micro that I had brought along with me. We composed a scene in which a French girl teaches Rowan’s character this tongue-twister: ‘Dido dined, they say, off the enormous back of an enormous turkey,’ which goes, in French, ‘Dido dîna, dit-on, du dos dodu d’un dodu

dindon.’ Rowan practised the Beanish character earnestly attempting this. In any spare moment in the film, we decided, he would try out his ‘doo doo doo doo doo’, much to the bafflement of those about him. It is about all I remember from the film, which over the next few months quietly, as 99 per cent of all film projects do, fizzled out. Meanwhile, journalism was taking up more and more of my time.

Britain’s magazine industry started to boom in the early to mid-eighties.

Tatler

,

Harper’s & Queen

and the newly revivified

Vanity Fair

, what you might call the Princess Di sector, fed the public appetite for information about the affairs of the Sloane Rangers, the stylings of their kitchens and country houses and the guest-lists of their parties.

Vogue

and

Cosmopolitan

rode high for the fashion-conscious and sexually sophisticated,

City Limits

and

Time Out

sold everywhere, and Nick Logan’s

The Face

dominated youth fashion and trendy style at a time when it was still trendy to use the word trendy. A few years later Logan proved that even men read glossies when he launched the

avant-la-lettre

metrosexual

Arena

. I wrote a number of articles for that magazine, and literary reviews for the now defunct

Listener

, a weekly published by the BBC.

The

Listener

’s editor when I first joined was Russell Twisk, a surname of such surpassing beauty that I would have written pieces for him if he had been at the helm of

Satanic Child-Slaughter Monthly

. His literary editor was Lynne Truss, later to achieve great renown as the author

of

Eats, Shoots and Leaves

. I cannot remember that I was ever victim of her peculiar ‘zero tolerance approach to punctuation’; perhaps she corrected my copy without ever letting me know.

Twisk was replaced some time later by Alan Coren, who had been a hero of mine since his days editing

Punch

. He suggested I write a regular column rather than book reviews, and for a year or so I submitted weekly articles on whatever subjects suggested themselves to me.

By now I had bought myself a fax machine. For the first year or so of my ownership of this new and enchanting piece of technology it sat unloved and unused on my desk. I didn’t know anyone else who owned one, and the poor thing had nobody to talk to. To be the only person you know with a fax machine is a little like being the only person you know with a tennis racket.

One day (I’m fast forwarding here, but it seems the right place for this story) Mike Ockrent called me up.

Me and My Girl

was by this time running in the West End, and we had all been thrilled to hear that Stephen Sondheim and Hal Prince had been to see it and had written to Mike expressing their admiration.

‘I told Sondheim that you have a fax machine,’ Mike said.

‘Right.’ I was not sure what to make of this. ‘I see … er … why exactly?’

‘He asked me if I knew anybody who had one. You were the only person I could think of. He’s going to call you. Is that all right?’

The prospect of Stephen Sondheim, lyricist of

West Side Story

, composer of

Sunday in the Park with George

,

Merrily We Roll Along

,

Company

,

Sweeney Todd

and

A Little Night Music

, calling me up was, yes, on the whole, perfectly all right, I assured Mike. ‘What is it about exactly?’

‘Oh, he’ll explain …’

My God, oh my good gracious heavens. He wanted me to write the book of his next musical! What else could it be? Oh my holy trousers. Stephen Sondheim, the greatest songwriter-lyricist since Cole Porter, was going to call me up. Strange that he was interested in my possession of a fax machine. Perhaps that is how he imagined we would work together. Me faxing dialogue and story developments to him and him faxing back his thoughts and emendations. Now that I came to think of it that was rather a wonderful idea and opened up a whole new way of thinking about collaboration.

That evening the phone rang. I was living in Dalston in a house I shared with Hugh and Katie and I had warned them that I would be sitting on the telephone all night.

‘Hi, is that Stephen Fry?’

‘S-s-speaking.’

‘This is Stephen Sondheim.’

‘Right. Yes of course. Wow. Yes. It’s a … I …’

‘Hey, I want to congratulate you on the fine job you did with the book of

Me and My Girl

. Great show.’

‘Gosh. Thank you. Coming from you that’s … that’s …’

‘So. Listen, I understand you have a fax machine?’

‘I do. Yes. Certainly. Yes, a Brother F120. Er, not that the model number matters at all. A bit even. No. But, yes. I have one. Indeed. Mm.’

‘Are you at home this weekend?’

‘Er, yes I think so … yup.’

‘In the evening, till late at night?’

‘Yes.’

This was getting weird.

‘OK, so here’s the deal. I have a house in the country and I like to have treasure hunts and competitions. You know, with sneaky clues?’

‘Ri-i-ght …’

‘And I thought how great it would be to have a clue that was a long number. Your fax number? And when people get the answer they will see that it’s a number and maybe they will work out that it’s a phone number and they will call it, but they will get that

sound

. You know, the sound that a fax machine makes?’

‘Right …’

‘And they will hear it and think, “What was that?” but maybe one of them, they will know that it is in actuality a fax machine. They might have one in their office, for example. So they’ll say, “Hey, that’s a fax machine. So maybe we have to send it a message. On a piece of paper.” And they will fax you for help.’

‘And what do I do then?’

‘Well, here’s the thing: beforehand, I will have faxed you their next clue. So when they fax you asking for help, you fax that clue back in return. You understand?’