The Giants and the Joneses (8 page)

Blood

G

RISHMIJ WAS WOKEN

by a scream and a shout of ‘Nug nug NUG!’ Was Jumbeelia having a nightmare?

Within seconds Grishmij was out of bed and on the landing. She opened Jumbeelia’s bedroom door, and the spratchkin streaked out.

‘Pecky,

pecky

spratchkin!’ yelled Jumbeelia. She was kneeling on the floor, cradling something in her hand, and tears were streaming down her cheeks.

Grishmij knelt down too, and put an arm round her. Jumbeelia had placed one hand on top of the other, hiding whatever it was she was holding.

Grishmij stroked Jumbeelia’s hair and asked her what the matter was. At first her granddaughter just sobbed, but at last the words came.

‘Grishmij! Grishmij! O spratchkin kraggled o iggly plop!’

Then Grishmij noticed the blood stain on the carpet. And as she looked at it, a fresh drop dripped from Jumbeelia’s hands – and another and another.

Jumbeelia looked down at the blood too, and then up at her grandmother through her tears.

‘Grishmij! Grishmij!’ she cried, and she lifted the hand that was hiding her secret.

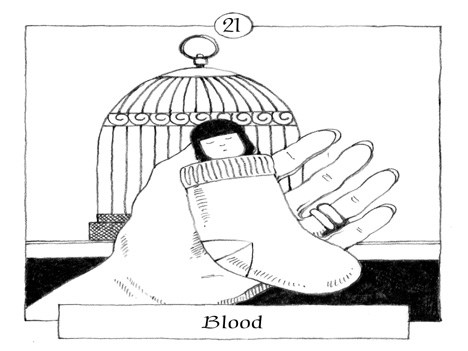

In Jumbeelia’s other palm lay a tiny white doll. It was dressed in a lacy nighty and a stripy football jumper.

‘Iggly plop! Iggly plop!’ Jumbeelia sobbed, as if the doll was real.

Grishmij was more concerned about the blood than the doll. How had Jumbeelia hurt herself? Had the spratchkin scratched her?

Jumbeelia shook her head. ‘Iggly plop,’ she kept repeating, and then, again, ‘O spratchkin kraggled o iggly plop.’

She held the doll out to her grandmother. ‘Oggle!’ she said. Grishmij took a closer look at it, and noticed something extraordinary. The blood was dripping out of the doll’s arm.

It wasn’t a doll. It really was an iggly plop. And what’s more, it wasn’t dead. It lay quite still but Grishmij saw it blink.

Very gently, Grishmij took the creature from Jumbeelia’s hand. She peeled off the football jumper. One sleeve came off easily but the blood from the wound caused the other sleeve to stick to the iggly plop’s arm. Grishmij continued to pull it, and with a little jerk it came away.

‘Ow!’ said the iggly plop.

Jumbeelia gasped. ‘Nug kraggled!’ she whispered.

Grishmij knew just what to do next. They took the iggly plop into the bathroom and Grishmij washed its arm. The wound was long but not as deep as she had feared. Jumbeelia fetched a handkerchief, and Grishmij

cut a strip off it which she made into a bandage.

The iggly plop was still quite floppy as Grishmij wound the bandage round and round its arm. Although it seemed to be aware of what was happening, it was obviously still suffering from shock.

Grishmij knew that birds and small animals could die of shock and she wondered if this creature would still be alive in the morning. Well, they could only do their best.

While Jumbeelia nursed the iggly plop, Grishmij fetched the old birdcage from the attic. It had sat there ever since Zab had let his canary escape. She gave it a good dust and put some cotton wool inside it.

The kitchen was the warmest room in the house, so they put the cage on the dresser. They filled the food and water containers with cornflakes and orange juice, which Jumbeelia seemed sure the iggly plop would like. Grishmij wondered how she knew this, but decided to save any questions for the morning.

They put the creature inside one of the socks which Grishmij had knitted for the bobbaleely, laying it gently

down on the cotton wool and covering it with a pile of handkerchiefs.

Only then did Jumbeelia clap her hand to her mouth and say, ‘O ithry iggly plop!’

Another one? Surely not? But Jumbeelia insisted that there

was

another one in her bedroom. They must find it and put it in the cage, to save it from the spratchkin.

After a quick and unsuccessful search of the messy bedroom, Jumbeelia agreed to go to bed, but only if they first shut the spratchkin in Zab’s bedroom.

In fact it was already in there, batting a plastic war figure about the floor. There was no sign of any bones or blood, so Grishmij managed to reassure Jumbeelia that it couldn’t have eaten the second iggly plop – if indeed it did exist.

She tucked her granddaughter up and went back to her own room.

She was just dropping off to sleep when she was woken again, this time by the ringing of the frangle on her bedside table. It was Jumbeelia’s father phoning from the hospital with the news they had all been waiting for.

Grishmij didn’t wake Jumbeelia again, but she looked forward to telling her in the morning that she had a new iggly sister.

Alone

C

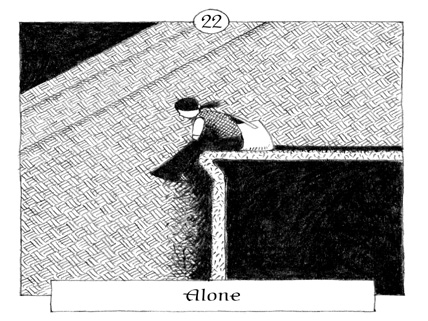

OLETTE SAT ON

the dark stair and shivered. Beside her lay the plastic railway line and her glittery running-away bag. The ribbon had been cutting into her shoulders, so she had taken the bag off for a quick rest. Not that it felt like a proper rest; Colette’s mind was too troubled for that.

Sitting there, she realised that this was the very same stair on which Zab had discovered them all – only about two weeks ago, though it seemed like a lifetime.

That was a dreadful moment, but at least they were all together then.

She had never felt so lonely in her life. Up to now there had always been Stephen or Poppy, and now there was no one.

Missing Stephen was an ache which Colette had grown used to, but missing Poppy was a sharp new pain. She could hardly bear to think about her little sister, and yet she could think of nothing else. Where was she? And was she alive or dead?

Colette realised how much Poppy had changed since their capture: she was no longer just a little pest; she had become a real friend. She had played her part in the milk raid so well, keeping still and then pulling the thread at just the right time to distract the kitten. She had done everything perfectly – right up until the last minute when, with her old fearlessness, she had rushed out of the doll’s house to try to save her big sister.

‘And now I’m going to save

you

, Poppy.’ Colette heaved the running-away bag on to her back and positioned the railway line once more.

The house was quiet. Colette knew that Jumbeelia

and the old lady had gone back to their bedrooms and that the monster kitten was safely shut away in Zab’s room; she had seen all this from the landing, where she had hidden earlier.

‘But please, no more phone calls!’ she said to herself. That sudden ringing, as loud as a fire alarm, had startled her so much that she had nearly fallen off her railway-line slide.

Poppy was downstairs somewhere, and that thought kept Colette going, step by step – slide, bump; slide, bump – right to the bottom of the giant staircase.

Which way now? When Zab had taken her and Stephen out into the garden he had turned left and carried them through a kitchen. That was as good a place as any to start looking for Poppy.

It was lighter down here; a lamp in the hall had been left on. In the distance Colette could see that the kitchen door was ajar, and she made her way towards it.

She was stopped in her tracks by a noise upstairs. The kitten was scratching at Zab’s bedroom door, trying to get out.

But it can’t get out, she told herself. It can’t. It won’t.

All the same, she started to run, the heavy bag bumping against the badge-shield on her back.

And now she was in the dark kitchen.

‘Poppy!’ she whispered.

She said it a little louder, but still there was no reply.

The distant scratching seemed to have stopped. The only sound was a low hum coming from the giant fridge.

As her eyes grew used to the darkness, Colette saw that there was a gap between the fridge and the cupboard beside it. She slid into it. The hum was horribly loud now, but at least this felt like quite a safe hiding place. She turned to have a better look at the room she was in.

A table and chairs. Cupboards. A stack of vegetable baskets beside a towering dresser. As she gazed up at the dresser, the moon came out from behind a cloud and shone through the kitchen window, and Colette saw the cage.

What was in it? A bird? A mouse? A hamster, perhaps?

It couldn’t be Poppy, could it?

‘Poppy! Poppy, are you there?’ Colette said it as loudly as she dared.

Silence.

‘Poppy! Poppy, are you all right?’

Still there was no sound from the cage. But there

was

a sound of loud footsteps outside the house.

A key turned in the back door. A sudden bright light flooded the room and Colette edged her way to the very back of the fridge and then behind it.

The fridge’s hum sounded louder than ever; and there was a different kind of humming too. Whoever had come into the kitchen was humming a cheerful tune. The voice was low – much lower than Zab’s voice. Could it be the giant father?

The humming stopped suddenly, in the middle of the tune.

‘Wahoy!’ Colette heard the giant man murmur. She heard his footsteps, followed by a softer, metallic sound. He must be opening the door of the cage.

Then she heard him gasp and exclaim, ‘Iggly plop!’

Beely bobbaleely

J

UMBEELIA’S FATHER

, P

IJ

, was scraping a carrot at the kitchen table.

The spratchkin jumped up and tried to bat it out of his hand.

‘Pecky, pecky, pecky!’ he said with a chuckle. He put down the knife and tickled the spratchkin under the chin. Then he pushed her gently off the table. He was in a good mood. As he began to cut the carrot into thin strips, he burst into song:

Beely beely bobbaleely,

Bobbaleely mubbin,

Oy whedderwhay woor

jum, woor chay

Fa sprubbin, sprubbin,

sprubbin!(Lovely lovely baby,

Baby mine,

You fill our home,

our land

With joy, joy, joy!)

It was an old song, and he had never particularly cared about the words before, but now they seemed full of truth and meaning. The new bobbaleely

was

beely. At five days old, she was absolutely beautiful, from the black hair on her pink head to her ten perfect iggly toenails. And tomorrow she would be coming home!

Pij got up and poked one of the carrot strips between the bars of the cage on the dresser. ‘Iggly plop! Iggly plop!’ he called softly.

Usually Jumbeelia or Grishmij fed the iggly plop, but this afternoon they were both at the hospital, visiting Mij and the new bobbaleely.

‘Beely frimmot!’ said Pij, waggling the carrot strip about in an attempt to coax the iggly plop from her nest.

Here she came at last. A sudden dart, and she had

snatched the frimmot from his hand.

She wasn’t much more than a bobbaleely herself, Pij realised. He was surprised at how protective he felt; maybe it was because he had first seen her the same night that his own bobbaleely was born. If only she wasn’t so timid! If she was this scared of him, how was she going to feel about Zab when he came home from Grishpij’s house tomorrow?

Pij had been hoping she would learn to say thank you. ‘Oidle oy! Oidle oy!’ he prompted her now, willing her to parrot the words back to him. Five days in the cage, and the iggly plop hadn’t spoken a single word of Groilish, though he, Grishmij and Jumbeelia had all been trying to teach her. Jumbeelia said that the creature

could

speak a different, nonsense language, but Pij had never heard her.

‘Oidle oy! Oidle oy!’ he repeated, but the iggly plop just backed away into her cotton-wool nest and nibbled at the strip of frimmot.

No one had yet dared to tell Mij about the new pet. Pij feared that she might hand the creature over to old Throg, or else dump her on the compost heap in the

garden, which is what she told him she had done with the iggly blebber.

If the iggly plop could learn to say just a few words of Groilish, maybe she would win Mij’s heart.

‘Wahoy! Wahoy, iggly plop!’ Pij tried again, but the only result was a chirrup and a soft thud from the spratchkin. It had leapt up on to the dresser and was staring intently at the cage.

The iggly plop trembled, cowered, and then burrowed under a handkerchief. Although her wound was healing well, her terror of the spratchkin was as great as ever.

Pij pushed the spratchkin on to the floor again, remembering the job he had been planning to do. He poked the remaining strips of frimmot into the cage, then fetched a saw and set to work on the back door. He was cutting out a square of wood from the bottom of the door, so that he could fit a flap for the spratchkin.

The spratchkin watched him briefly, but then padded to her favourite place, which was beside the fridge. She shot a paw down one side of it. A dusty pea rolled out. Instead of playing with it, the spratchkin continued to crouch, wriggle her haunches and stare at the dark gap. Pij wondered if she had seen a mouse, but he was too happy sawing away to bother to investigate.

As he sawed, he struck up the song again:

Beely beely bobbaleely,

Bobbaleely mubbin,

Oy whedderwhay oor jum, oor chay

Fa …

He paused to push at the square of wood, which clattered to the floor. At the same time an iggly voice from the cage completed the last three words of the song:

‘Sprubbin! Sprubbin! Sprubbin!’