The Giants and the Joneses (5 page)

Whackleclack

O

LD

T

HROG KNELT

in the mist, a pointed stone in his hand and a boulder on the ground in front of him.

He had never tried stone-carving before, and it was hard work. Throg had cut himself twice, and some of the letters looked a bit crooked. But that didn’t matter: it was the words themselves which counted, not how they were written.

Throg’s heart swelled with pride as he thought how

giants for generations to come would look at this boulder and the writing on it:

ISH EZ QUEESH THROG KRAGGLED O BIMPLESTONK.

(THIS IS WHERE THROG KILLED THE BEANSTALK.)

They would rejoice and remember the courageous old giant who had saved them from an invasion of iggly plops.

Still swollen with triumphant thoughts, he climbed back over the wall and hobbled along the narrow road which led to the town.

Only when he passed the field where he had dozed the other day did his mind take a different course. He remembered the grinning girl he had seen walking along the same road, and the recollection sparked memories of his own childhood.

Throg’s earliest memory was of a toy, a furry animal called Lolshly. The word lolshly meant white, but Throg could only remember his Lolshly being

a dirty brownish colour.

Young Throg and his Lolshly had been inseparable: he cuddled the toy in bed and took it everywhere with him. His mother, he remembered, had been less enthusiastic. She said that Lolshly was dirty and smelly and needed a wash. But Throg had refused to hear of such a thing: it was the smell that he

liked

; he would press his nose against Lolshly’s body and take deep comforting breaths while he twiddled tufts of grubby fur between finger and thumb.

And then one day Lolshly had disappeared. Throg had fallen asleep in the pram and when he woke up the toy had gone. Vaguely he remembered the search, the tears, the offer of a replacement which he turned down angrily:

nothing

could replace Lolshly. But what he remembered most clearly was his mother telling him that the iggly plops must have taken it.

That was the moment that Throg’s hatred for the iggly plops had been born. His search for Lolshly became a search for the tiny wicked thieves who had taken his toy.

He never found a single iggly plop. He told himself that they must have returned to their own land. But he was in no doubt that they were determined to come back one day – just as determined as he was to stop them.

And now he

had

stopped them! Throg felt another surge of joy and, to match his mood, the sun came out from behind a cloud. It shone brightly and the whole world shone back at it: the raindrops on the grass blades glinted, the buttercups glowed, and even the road seemed to glitter … wait a minute, what

was

that bright iggly thing in the middle of the road?

Throg had always prided himself on his excellent eyesight, and even in his old age this was as keen as ever. He bent down to inspect the tiny object in the road.

It was white, and igglier, much igglier, than a jewel in a ring.

It was shiny, and round, and flat, and it had two holes in the middle of it.

It was a whackleclack, the iggliest whackleclack that Throg had ever seen, a whackleclack so iggly that it could only belong to an iggly plop.

The icy lake

‘B

OAT ALL STICKY

,’ said Poppy.

‘It’s not a boat, it’s a soap dish,’ said Stephen.

Colette said nothing. She was feeling seasick. Their soap-dish boat heaved on the bathwater waves, and above them the frightening, grinning face of the boy giant loomed over the side of the bath. He was the one creating the waves, by churning up the bathwater with his hands. The more distressed the children grew the more he grinned.

Now he turned on the cold tap again, and their soapy tub spun round. Colette held on to the edge, feeling giddy, and the giant boy laughed.

‘Stop it, you slimy slug!’ Stephen shouted. In reply, their tormentor splashed some water over the edge of the soap dish.

‘Don’t shout at him like that – do you want him to capsize us?’ said Colette.

Almost as if he understood her, the boy giant sloshed some more water into their boat.

‘All wet,’ said Poppy.

The cold water was up to their knees now, that is when they could manage to stand; but the slippery floor and the movement of the boat kept overbalancing them, and they were soon soaked through.

The soap dish was sinking lower and lower in the water.

‘Wunk, twunk, thrink … GLISHGLURSH!’ shouted the boy giant, and an enormous wave crashed over their heads.

Colette gulped a great mouthful before she was swept under the water. It swirled her round and pressed

on her from all directions. She hardly knew which way up she was.

No, no, no

, she said to herself.

I will not drown in a giant’s bath

. Her arms and legs went into action.

Just as she felt she could hold her breath no longer, her head came out of the water.

She spluttered and opened her eyes. There was Stephen, treading water and looking wildly around him. She knew he wouldn’t drown. He had been to lifesaving classes.

And then she heard Poppy scream.

Her little sister was thrashing about, clinging to the edge of the soap dish as it sank under the water. She couldn’t swim.

But now Stephen had reached her and was on his back, his hands under her armpits. ‘Keep still, Poppy – don’t panic!’ he said.

Poppy stopped struggling and allowed Stephen to propel her in circles round the bath. But how long could he keep it up? And how long could Colette carry on treading water like this? The water was like an icy lake. Her arms and legs were beginning to feel quite numb.

Above them came the awful laugh again.

‘Heehuckerly iggly plops!’

‘It’s not

funny

, you scorpion!’ spluttered Stephen.

The boy giant reached out for the tap and turned it off.

‘At least the current won’t be so strong now,’ said Colette.

She kept her eye on the giant hand. It moved towards the chain between the two taps … the chain which was joined on to the plug.

‘Wunk, twunk, thrink … HAROOF!’ He pulled the chain.

Good, was Colette’s first thought. The water level would go down. They wouldn’t have to keep swimming for ever.

But then she thought about what happens when a bath empties. She thought about the whirlpool of water being sucked down the plughole at the very end. And she thought about the plughole itself, and the holes in it.

Surely the holes in a giant’s plughole wouldn’t be big enough for a human being to slip through?

She hardly took in the sound of the front door and

the footsteps on the staircase. But she did hear the voice.

‘Zab! Zab!’

It was Jumbeelia.

‘Zab! ZAB! Queesh oor oy?’ She was just outside the bathroom door.

Suddenly Jumbeelia, their kidnapper, felt like a rescuer. Please come and find us, Jumbeelia. Please! Come in now!

Colette thought it, but Poppy shouted it.

‘Big girl! Come here!’

And Jumbeelia did.

The girl giant’s voice dropped to a whisper, but it was a furious-sounding whisper.

‘Zab! Uth oor

mub

iggly plops! Niffle uth abreg!’ she hissed.

The boy giant’s voice dropped too. Obviously neither of them wanted their mother to hear.

‘Uth oor

mubbin

!’ he said.

‘Nug! Uth oor

mubbin

!’ replied Jumbeelia, pointing to herself before coming out with some more angry sounds.

‘I think they’re arguing about who owns us,’ said Colette.

‘

Nobody

owns us!’ said Stephen angrily.

Meanwhile the level of the bath was steadily sinking. Colette began to feel herself being pulled towards the plug end. She tried to swim against the current, but only managed to stay in the same place.

Jumbeelia reached into the bath but Zab grabbed her wrist.

Now the girl giant’s tone of voice changed: she seemed to be pleading with him, maybe even to be offering something.

’Queesh?’ whispered Zab. He sounded interested.

Colette heard Jumbeelia go out, and her heart sank.

The tug of the plughole was becoming stronger. Stephen, still on his back with Poppy in his grip, had been sucked towards it and was swimming in helpless circles around it.

‘Come back! Come back, big girl!’ Poppy cried.

‘Shhhh!’ said the boy giant. He leaned over and fished the soap dish out of the water. Roughly, clumsily, he grabbed Stephen and Poppy and put them into it. The next second Colette was beside them. The three of them huddled together on the

slippery floor of what had been their boat.

Poppy whimpered and Colette tried to comfort her.

‘We’ll be all right. At least we’re not going to drown,’ she said.

They were no longer on the bath sea, but in the air, borne aloft by Zab.

‘He’s taking us back to Jumbo’s room,’ muttered Stephen, shivering in his soggy ballet dress as they lurched along.

They peered over the edge of the soap dish and saw Jumbeelia with something in her hand.

‘Iggly strimpchogger,’ she said.

‘It’s our lawn mower!’ said Stephen indignantly.

Zab was clearly impressed. He put the soap dish down on Jumbeelia’s floor and grabbed the lawn mower. They saw him turn the key in the ignition and beam when the engine started up.

‘Sweefswoof?’ asked Jumbeelia.

‘Ootle rootle,’ said Zab, and he picked up Poppy.

Stephen was still incensed about the lawn mower. ‘They’re thieves, all of them!’ he said.

‘I think they’re doing a swap,’ said Colette, remembering how she had once swapped all the toy cars she had collected from cereal packets for the shells Stephen had brought back from a school trip.

Sure enough, Zab handed Poppy over to Jumbeelia.

‘Big girl! Nice big girl’ cried Poppy. Jumbeelia kissed her and then reached down for Colette and Stephen.

Colette felt ridiculously pleased. Although their escape attempt had failed, anything was better than being at the mercy of Zab.

But Zab was too quick for Jumbeelia. He snatched the soap dish, and Colette and Stephen went whizzing up in it, high above his head.

They heard Jumbeelia protest: ‘Niffle uth abreg! Niffle uth abreg!’

Zab laughed his nasty laugh. ‘Wunk iggly plop – wunk iggly strimpchogger,’ he said.

And though Colette didn’t understand the words themselves, she did understand what had happened.

Zab had swapped Poppy for the lawn mower. But he was going to hang on to Colette and Stephen. It was Finders Keepers.

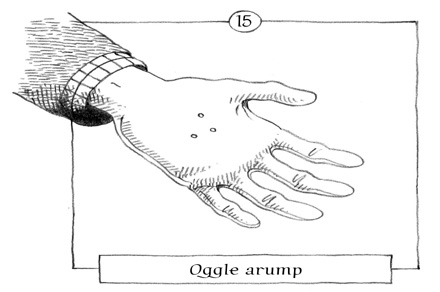

Oggle arump

O

LD

T

HROG NO

longer spent his days walking round the edgeland. Instead, he walked round the town. In his hand he held the three whackleclacks he had now found.

He had made up a new rhyme. It went like this:

| Iggly plops! Iggly plops! Queesh? Queesh? Queesh? Oggle arump! Oggle arump! Aheesh! Aheesh! Aheesh! | Little people! Little people! Where? Where? Where? Look around! Look around! Help! Help! Help! |

Throg knocked on door after door. ‘Ev oy oggled o iggly plops?’ he asked, but time after time he was told that no, no iggly plop had been seen. He held out the three whackleclacks, but time after time he was told that they must have come off a doll’s dress.

‘Roopy floopy plop,’ people murmured behind his back. The poor old man was harmless, but quite mad. It was a shame he wouldn‘t agree to go into an old giants’ jum, instead of wandering about reciting his strange rhymes.

Today, Throg walked up the front path of a house on the outskirts of town. He had tried this house before but never found anyone in.

He rang at the bell and a woman came to the door.

He asked her the usual question, ‘Ev oy oggled o iggly plops?’ and received the usual pitying look and the usual answer, ‘Nug.’

Throg looked at the woman suspiciously. You couldn’t trust anyone. He thought for the thousandth time of the old (but true) bimplestonk story, the one in which the iggly plop had stolen the giant’s harp and hen. In that story the giant’s wife had hidden the wicked iggly plop from her husband and lied to him. For all he knew, this woman could be lying too.

A girl appeared in the doorway. Throg recognised her – it was the policeman’s daughter. She was complaining loudly about how her brother had stolen her collection of conkers, but when she saw Throg she broke off and hid behind her mother’s back.

Her mother smiled apologetically, then said ‘Yahaw’ and closed the door.

Throg stood for a second on the doorstep before setting off on his way. Something was bothering him. Some memory was refusing to come to the surface.

He shrugged and walked back down the path to the road. And then he remembered. This was the same stretch of road where he had found the whackleclacks.

Throg scratched his head and thought. He couldn’t quite work it out but it was all very suspicious. He never had trusted the police. He would certainly keep an eye on that house.