The Giants and the Joneses (9 page)

The bridge of doom

A

T LAST THERE

was a way out!

And at last it was safe to tell Poppy. The kitchen was dark and the house was quiet. All the giants must be in bed.

Colette stepped out from her hiding place. It was always a relief to get away from the deafening hum of the fridge. She had spent five days behind it, with only Poppy’s leftovers and anything else she could scavenge during the night to eat.

‘Poppy! Poppy, are you awake?’

‘Yes. I got carrots,’ said Poppy proudly. ‘One, two, three, throw.’

A piece of giant carrot as long as Colette’s arm landed on the floor.

‘Good shot, Poppy,’ said Colette. (Poppy’s leftovers often landed, uselessly, on the surface of the dresser.) ‘But I won’t eat it now. We can take it with us.’

‘Take it in the garden, see Stephen?’ asked Poppy.

‘Yes,’ said Colette, trying not to sound doubtful. She didn’t really know if Stephen

was

still in the garden – she hadn’t heard the lawn mower for days – but there was no point in worrying Poppy. Instead, Colette told her, ‘There’s a cat-flap. We can escape!’

‘No,’ said Poppy. ‘Naughty cat might get us.’

‘We’ll be fine,’ said Colette, as confidently as she could. ‘It won’t get us. It’s upstairs, I’m sure.’

Poppy didn’t answer straight away. Then she said, ‘All right,’ very quietly.

Colette was scared of the giant kitten too, but her main fear was a different one. Before they could escape she would have to climb up and rescue Poppy from her

cage, and she didn’t know if she had the strength to do it. Inside her cage, Poppy had been fed and pampered by the giants. Her arm had nearly healed and she had put on weight. But as Poppy had grown stronger, Colette, living on a diet of scraps and leftovers, had become weaker.

A worse problem than hunger was thirst. If it wasn’t for the juicy tomato which had rolled out of a shopping bag, unspotted by the giants, Colette thought she might have died. She had hidden the tomato behind the fridge and had been nibbling and sucking away at it for the last few days.

Peering up through the gloom at the cage on the dresser, she suddenly felt dizzy. And I haven’t even started climbing yet, she thought.

Beside the dresser stood the tall stack of plastic vegetable baskets. They reminded Colette of something. What was it?

Then it came to her. ‘The Death Tower,’ she said out loud.

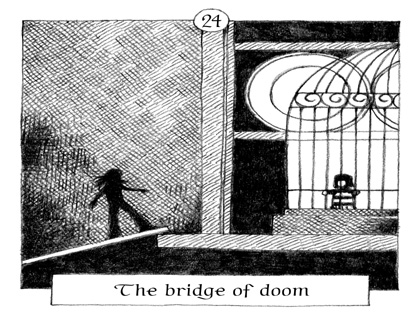

That was Stephen’s name for one of the climbing frames in an adventure playground back home. The

Death Tower was taller than a house and had five platforms. To reach the top one you had to walk along a scary sloping bridge which Stephen called the Bridge of Doom.

Stephen absolutely loved that sort of thing, but Colette had only climbed the Death Tower once, to prove to him that she wasn’t the ‘cowardly cockroach’ he kept calling her. She could still feel the wave of dizzy panic that had hit her when she’d made the mistake of looking down from the Bridge of Doom.

If only Stephen were here now! But it was no use thinking that.

‘I’m coming, Poppy,’ she said, and set out across the kitchen floor, dragging the length of yellow plastic behind her. It had been a railway line and a slide, and now it was going to be a bridge.

The vegetable baskets were high at the back and sides but low at the front. It was easy enough to heave herself into the bottom one, which was full of giant potatoes.

Colette clambered up the round dirty boulders to the top of the potato hill. She reached up to dump the railway line into the basket above. Then, gripping the

front rim of the basket, she managed to swing herself up into it.

Onions this time. It was harder to climb them because their papery skins kept flaking off. As her fingernails scrabbled at the flesh beneath the skins her eyes began to sting from the onion juice, and soon they were streaming with painful tears. Still, she struggled to the top and heaved herself up to the next basket.

‘Nearly there now?’ came Poppy’s voice, as if Colette was on a car journey.

‘Yes, nearly there,’ said Colette, though there were still two more baskets to go. As it turned out, these were full of parsnips and carrots, which were quite knobbly and so easier to climb than the round potatoes and onions.

Now came the really tricky part. The rim of the top basket was very nearly as high as the surface of the dresser, but there was a gap between them.

‘This is where you come in,’ she said to the railway line. It felt like a kind of friend now. After all, it had got her all the way down the giant stairs. But it was one thing sliding down a carpeted staircase, step by step,

and quite another to cross a narrow bridge with no railing – especially in the darkness, when the bridge sloped and the drop below her was as deep and steep as a mountain canyon.

‘I mustn’t look down,’ thought Colette, remembering the Death Tower again. The plastic bridge (she tried not to think of it as the Bridge of Doom) was in place now, but she was terrified that it would slip. She tested it with one foot and then the other. It felt firm enough – a lot firmer than her legs, which had suddenly started to wobble.

‘Come on, ’Lette,’ said Poppy. Colette could see her now, holding the bars of the cage and jumping up and down. Somehow the sight gave her strength, and before she knew it she had crossed the bridge and was on the dresser beside the cage. Poppy’s delighted face and cry of‘ ’Lette here!’ were her reward.

Colette tried to reach the metal hook of the cage door, but it was just too high. She looked around the surface of the dresser for something she could use to yank it.

Near the cage was a giant ashtray and in it a match

as long as a human-size walking stick. Holding it above her head, she thrust it up against the hook.

Yes! The hook rose, the door swung open and Poppy ran out of the cage.

She flung herself at Colette like a puppy. Colette fell over backwards, with Poppy on top of her. They both laughed with the relief of being together again.

Then there was a clattering sound and they stopped laughing. The railway line had fallen to the floor.

‘Bridge gone,’ said Poppy.

They were stranded on the dresser.

This was too much to bear. Colette sat down and held her head in her hands.

‘Have nice carrot,’ suggested Poppy, trying to cheer her up.

Colette shook her head and shivered. Poppy went back into the cage and brought out her bedding: a knitted giant baby’s sock and a giant handkerchief. She wrapped the handkerchief round Colette’s shoulders.

‘Nice warm sheet,’ she said – and suddenly Colette knew what to do.

‘Are there any more of these?’ she asked.

Poppy dragged out four more handkerchiefs.

Colette wasn’t an expert on knots like Stephen, but she thought she could remember how to tie a reef knot, even in the dark. Her fingers set to work.

Poppy realised immediately what she was doing.

‘Go down sheets, go in garden, see Stephen,’ she said.

‘Yes,’ said Colette.

‘Take cosy bed too,’ said Poppy, giving the sock a push. The matchstick fell down with it.

Colette was surprising herself with her knot-tying speed and skill. Soon all five handkerchiefs were tied together. She tied the top one to a bar of the cage and pushed the sheet ladder off the edge of the dresser. Would it be long enough? Yes – she could see that the last handkerchief was touching the kitchen floor.

‘Like the Donkey,’ said Poppy.

The Donkey was another climbing frame at the adventure playground. It had a tail made of knotted rope, which Poppy could confidently climb up and down. Remembering this stopped Colette feeling too nervous.

‘I’ll go first,’ she said.

Hand over hand, she lowered herself to the floor. It was much quicker and less scary than climbing the vegetable rack had been.

Watching Poppy was worse, but Colette made herself remember the Donkey, and sure enough her little sister climbed down fearlessly and easily.

What a relief to be down on the ground again! At least, for Colette it was; Poppy was looking round the dim kitchen anxiously as if she expected the kitten to appear at any moment. Colette led her to the back door where the new cat-flap had been fitted.

‘Too high,’ said Poppy.

‘It’s all right – we can make a ramp with the railway line. I’ll go and find it. Do you want to come with me?’

But Poppy was staring, horrified, at the cat-flap. Colette looked at it too, and had the impression it was moving slightly.

‘Cat coming,’ said Poppy in terror.

‘Quick! Run!’ Colette grabbed Poppy’s hand and together they ran for the gap beside the fridge. They reached it safely and peeped out.

Yes, the cat-flap was definitely lifting slowly towards them. And now something was appearing from underneath it. Something pale and round. A face.

‘Stephen!’ shouted Poppy.

Escape

T

HE LAWN MOWER

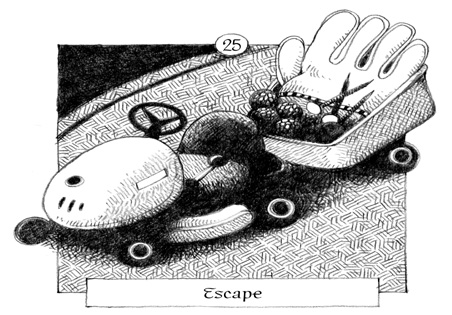

stood waiting on the moonlit path.

Stephen could guess exactly what Colette would say when she saw what was in the trailer: ‘Stephen Jones, you’ve turned into a collector!’ He tried out various replies in his head.

But Colette didn’t say it. In fact, it was all she could do to climb into the trailer. He was shocked to see how weak she seemed. She looked thin and dirty too.

‘You’re even more of a fright than I am,’ he joked.

Colette smiled faintly, but all she said was, ‘I’m so tired, Stephen. I just want to lie down.’

‘Well, you can,’ he told her, patting the giant gardening glove that filled up half the trailer. ‘This bed’s got compartments for all of us, and a couple to spare. And there’s some thistledown inside that makes it quite cosy.’

Poppy, who didn’t seem at all tired, helped him tuck Colette up in one of the fingers of the glove.

‘I found it under the shed,’ he said proudly. But Poppy was more impressed by the pile of giant blackberries as big as footballs.

‘Help yourself,’ he said, clambering into the driver’s seat. He started the lawn mower up.

‘All bumpy,’ complained Poppy, as they jolted down the garden path.

‘It’s this gravel – it’s like boulders,’ said Stephen. ‘It’ll be smoother once we’re on the road.’

And so it was. They drove through the night. Colette was asleep, and Poppy was too busy gorging herself on the juicy bobbles of the giant blackberries to talk much.

‘Stephen have nice black’by?’ she said at last, offering him one.

‘No, I’m sick of them. They’re just about all I’ve had to eat.’

They drove on in silence for a while. Then, ‘Go to beanstalk, climb down?’ asked Poppy.

‘That’s right,’ said Stephen. But he was beginning to feel uneasy. He had been looking out for the buttons that Colette had dropped when they were captured, but he hadn’t spotted any of them.

They came to a crossroads, and Stephen parked the lawn mower under an overhanging leaf. Which way now?

Colette woke up. After eating a whole blackberry she was more like her old self – annoyingly so.

‘Stephen Jones, you’ve turned into a collector!’ she said, exactly as he knew she would. As well as the glove, the blackberries and some extra thistledown, there was a stack of curly giant parsley and some garden nails as long as swords.

‘Ah, but my collections are to keep us alive. I don’t collect

useless

things.’ He eyed the glittery bag which

she had insisted on bringing with her.

‘This is the running-away bag,’ protested Colette. ‘It’s

full

of useful things.’

‘Like food?’ he asked hopefully.

‘No,’ admitted Colette. ‘Well, there’s a bit of carrot. We did have some other food, but we finished it all ages ago. Jumbeelia stopped feeding us, you see.’

‘Big girl got snails,’ explained Poppy.

‘I expect she’s gone off them too,’ said Colette. ‘None of her crazes seem to last very long.’

‘That’s the trouble with you stupid collectors,’ said Stephen.

‘So you think these are stupid then, do you?’ Colette emptied the bag and produced his very own jeans and long-sleeved T-shirt.

‘Cool! Where did you find these?’ Stephen was already ripping off his thin torn floppy soldier’s outfit.

‘On the washing line Jumbeelia collected. We packed a sheet and a towel from it too. And look at these other things.’

Stephen inspected the giant items that Colette had tipped out of the bag. Three badges, three acorn cups,

a few sweet papers, a matchstick, a baby’s sock and some feathers.

‘The badges are good,’ he said, ‘and I suppose the matchstick is OK.’

‘It’s more than OK,’ said Colette. ‘I opened Poppy’s cage with it.’

‘And that sock thing looks quite warm,’ he admitted grudgingly. ‘But why the feathers?’

Colette looked a bit sheepish then. ‘Well, they don’t weigh much,’ she said. ‘Anyway, you know what Poppy’s like about feathers. She just fell in love with them.’

Typical, he thought. ‘And I suppose she fell in love with these stupid acorn cups – or are they in aid of anything?’

‘Get water?’ suggested Poppy. It had been raining the day before, and she climbed down and filled one with water from a puddle.

‘It doesn’t look very clean,’ said Colette, but they were too thirsty to worry about that. They ate another blackberry between them and nibbled some of the parsley, while Stephen told them all about his time outdoors – the days spent hiding and hunting for food,

and the night-time searches for a way into the house.

‘What about all the creepy crawlies?’ asked Colette.

‘I think most of them were more frightened of me than I was of them. The worst thing was that cat – always nosing around under the shed.’

‘Naughty cat,’ said Poppy, looking around as if she half-expected it to be coming down the road.

But the road was empty, although the sky was light by now.

‘Hadn’t we better be going?’ asked Colette.

‘Yes, but which way? I haven’t found any of your famous buttons yet.’

‘We might now that it’s daytime. Why don’t we each look down a different road?’

Stephen agreed, but he searched with a heavy heart. He had a horrible feeling they might have gone the wrong way in the first place.

Poppy treated the button-hunt as a party game. ‘I find flower! I find stick!’ she shouted, and then, extra loud, ‘I find poo poo!’

‘Well, don’t tread on it!’ Stephen shouted back.

‘Little poo poo. Baa Lamb poo poo!’ said Poppy.

Stephen and Colette came to look.

‘They’re probably from a giant mouse,’ said Colette.

‘No – I know what those look like,’ said Stephen, whose time in the garden had turned him into something of an expert. ‘These ones

do

look like sheep droppings – normal sheep, I mean, not giant ones.’

‘But Jumbeelia’s mother put the sheep down the …’ Colette stopped, but Poppy couldn’t hear her anyway. She had wandered a bit further down her road, and she now called out, ‘More poo poo!’

‘We may as well go that way,’ said Stephen, and they climbed back into the lawn mower.

They followed the trail of droppings for a mile or so. Then, ‘I’m sure the beanstalk wasn’t this far away,’ said Colette. ‘Shouldn’t we go back, Stephen?’

‘We can’t. We’re nearly out of petrol.’

Almost as if the lawn mower heard him, its engine noise spluttered and then died, and they came to a stop.

‘Oh no,’ said Colette. ‘We’ll have to walk.’

‘Don’t want to walk,’ said Poppy.

‘You wimpy woodlice,’ said Stephen, but his heart wasn’t really in insulting them. He was too worried.

Suddenly he felt very tired. He hadn’t slept all night. Neither had Poppy. Colette was better rested, but she still seemed very weak.

Still, there was no choice. The girls realised it too. They wrapped a few of the firmest blackberries in sweet papers, and stuffed them into the bag, along with the nails and some of the thistledown. Colette shouldered the bag wearily, while Stephen dragged the glove-bed behind him.

As they trudged along the road he couldn’t resist a glance back at the lawn mower. He hated leaving it there. He had been cherishing a wild hope that he could somehow get it safely down the beanstalk.

To his surprise, he could only just see it. It was shrouded in mist. Stephen realised that the air around them was growing thick, cold and white.

‘This feels right,’ said Colette.

And then, without warning, the road just stopped. In front of them was an enormous stone wall.

‘What do we do now?’ asked Stephen.

‘Go through hole,’ said Poppy, pointing to a gap between some of the lowest stones.

The other side of the giant wall, the mist was thicker still. ‘Let’s hold hands,’ said Colette.

The ground was bare and slippery and the air cold and clammy. They shuffled forwards together.

‘If you were a giant you wouldn’t even be able to see the ground,’ said Stephen.

‘I can, though,’ said Colette, ‘and I can see a button!’ She picked it up triumphantly. ‘So we

are

on the right track!’

Just then, they heard a muffled bleating.

‘Baa Lamb!’ shouted Poppy. She broke free and started to run.

‘Stop! You might fall off the edge!’ Stephen caught up with her, grabbed her elbow and slowed her down.

The bleating came again, and at the same time the mist thinned slightly and they all saw Baa Lamb. He was standing at the very edge of the land, gazing out into the empty space beyond. He looked tattier than ever. The end of one of his twisty horns had broken off, and his wool was full of bits and pieces, as if he had been rolling about in a giant compost heap.

‘Baa Lamb!’ Poppy cried again, reaching out to him. The sheep remained still, gazing down, and Stephen thought he had a forlorn look about him.

‘And look, another button!’ exclaimed Colette. ‘So the beanstalk must be just here.’

But it wasn’t.