The Good and Evil Serpent (40 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

In the Bible, dogs appear in a negative light. As R. de Vaux stressed in his lectures on daily life during the monarchy, the dog was the garbage man in Jerusalem and elsewhere.

306

The hunter dogs so familiar in Egyptian scenes and Assyrian lore are singularly absent from the Bible. In the Old Testament we learn about pariah dogs.

307

In the New Testament, we hear Jesus warning about giving what is holy to dogs (Mt 7:6), and a woman telling Jesus that she is willing to lap up crumbs under the table like a dog (Mt 15:26#x2013;27). We also learn that Lazarus is visited by dogs (Lk 16:21), that Paul uses the dog negatively (Phil 3:20), and that the author of Revelation has dogs cast out of the blessed city (Rev 22:15).

Although in Arab countries today the dog is shunned as unclean because it is a scavenger, and although in Greek mythology the evil goddess Hecate is accompanied by fierce fighting dogs, the dog is almost always seen as a positive symbol in Greek and Roman mythology.

308

Not only Hermes and Asclepius had companion dogs, but so did the saints, especially Hubert, Eustace, and Roch.

309

Perhaps the dog represented the faithful companion of the human (the

viator

on the eternal

via

).

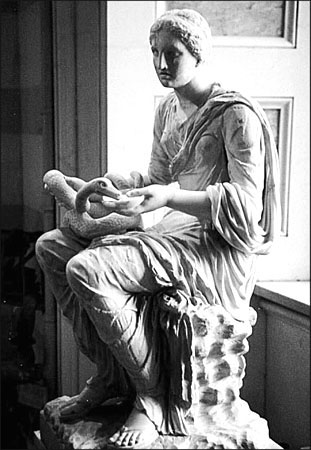

Figure 60.

Hygieia. Greek or Early Roman Period. Courtesy of the Hermitage. JHC

Asclepius, the son of Apollo, was the quintessential patron of physicians. One of his devotees may have been Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine. Galen was devoted to him. The Hippocratic oath, now sworn to by modern physicians, at least in the West, used to begin as follows: “I swear by Apollo the healer, by Asklepios, by Hygieia, by Panakeia and by all the powers of healing, and call to witness all the gods and goddesses that I may keep his Oath and Promise to the best of my ability and judgement.”

310

Hygieia

Hygieia, the daughter

311

of Asclepius “who is worth as much as all” his other offspring,

312

is often depicted on coins feeding a serpent.

313

She is the goddess of health and hygiene.

314

It is from her name that the word “hygiene” derives. She is often depicted with a serpent eating from her hand or from a bowl that she is holding. This image appears in statues

315

and on coins celebrating her cult.

316

Some of these coins were minted at Tiberias during the time when Trajan was emperor (98#x2013;117

CE

), at Neapolis (Shechem) during the reign of Antoninus Pius (137#x2013;61

CE

), and at Aelia Capitolina in the third century

CE

.

317

Coiled serpents often appear on coins symbolizing the cult of Demeter and of Roman emperors.

318

Hygieia is depicted in

Fig. 60

with a large serpent eating out of a bowl in her hand (as is customary, it is her left hand). This sculpture is superior to the ones I examined in the Metropolitan, British Museum, and at Epidaurus and Athens. Notice the way the artist portrayed the serpent as friendly and attractive. This example in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg

319

dates from the end of the first century

BCE

.

A marvelously sculptured statue of Asclepius with Hygieia and a large serpent, winding up Asclepius’ staff, across his lap, to eat from Hygieia’s right hand, is preserved in the Vatican Museum.

320

It dates from the Imperial Empire. A similar one is to be found in Turin, in the Palazzo Reale.

321

It is also from the Imperial Empire. Whether in elegant works, such as the ones just mentioned, or crude etchings on stone, Hygieia almost always appears with a serpent. As

salus

(“health” in Latin) she is found in the famous Fontana di Trevi in Rome.

What is the meaning of this symbolism? Hygieia is not depicted erotically and the serpent does not have phallic features or functions. The serpent appears as gentle and affectionate;

322

and when resting on Hygieia’s bosom it is below her breasts and not evoking any sexual overtones.

323

Her gaze is away from the serpent and often upward. Typically, as in the example preserved in the Hermitage, her gaze is pensive and directed to something far off. Her association with Asclepius and her portrayal in literature make it certain that the serpent with her depicts health, the return to health, and one of the main sources for healing. Thus, Hygieia is the goddess of health, and the serpent is her symbol. Because she is an incarnation of health and healing, so the serpent is a symbol of that incarnation. This insight is in line with, but also a significant development beyond, what we contemplated when working on serpent symbolism in ancient Palestine, especially with Jericho’s “Elegant Bird Vase with Two Serpents” and the incense shrines at Beth Shan.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SNAKES IN THE CLASSICAL WORLD: GENERAL QUESTIONS AND CONSIDERATIONS

Snakes in the Greek and Roman Home

In many Greek homes, snakes were pets. This fact constitutes a category outside of ancient serpent iconography, but it is important for comprehending its setting. The snakes served to protect the house from vermin, rats, and other undesirable small animals.

324

In Roman society, the serpent sometimes represented the paterfamilias (“father of the family,” or the head of the house).

325

Serpents are also associated with the tombs of one’s parents. Indeed, in Virgil’s

Aeneid

5.83ff, it is a serpent who accepts the food Aeneas left at the grave of his father. Pliny in his

Natural History

stated that after the Asclepian cult was brought to Rome a snake was “commonly reared even in private houses [

in domibus

].”

326

The ancients played a came called

mehen

, which means “coiled one”; the roundel, or game board, is often carved with the face of a serpent that is coiled up.

327

The game boards have been found especially in Egypt, as early as the fourth millennium

BCE

, but also in Crete, many Aegean islands, Cyprus, Lebanon, and Syria.

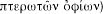

Figure 61.

Greek Vase Detail. Courtesy of the Hermitage.JHC

What Is the Meaning of Serpent-drawn Chariots?

An ornate sarcophagus is on display in the Archaeological Museum in Basel, Switzerland. It depicts two large serpents in high relief and with wings pulling a chariot in which a woman is standing. The woman is identified with Medea.

328

This iconography is also found, and in stunning fashion, on the Medea sarcophagi on display in Berlin in the Pergamon Museum,

329

in the Museum in Ostia Antici,

330

and in the Thermen Museum in Rome.

331

It is obvious now why artists often placed depictions of serpents on sarcophagi,

332

but why would one depict serpents pulling chariots? Is this iconography not patently absurd?

The answer is “no”—or at least not for the ancients. In antiquity, others besides Medea were depicted with serpents drawing chariots. These include heroes, gods, and goddesses (but no heroines as far as I have been able to detect).

333

Medea’s lover and husband who betrayed her, Jason, also is shown in a chariot that is pulled by two fierce serpents with beards or goatees.

334

Aphrodite often appears in a chariot pulled by powerful serpents.

335

Tellus (a divinity that represented the earth) is depicted in a chariot drawn by two serpents.

336

Paidis iudicium

appears in a chariot pulled by two serpents with beards or goatees.

337

Amor or Cupid is chiseled on a sarcophagus; she is shown with two serpents pulling a chariot.

338

Pluto, with Persephone, appears on two sarcophagi; he is in a chariot pulled by two serpents.

339

Persephone is shown sitting in a chariot that is pulled by serpents,

340

and once she is with a caduceus.

341

Ceres is shown with two serpents drawing a chariot on numerous sarcophagi and on a plate.

342

Ianitor Orci appears in a scene with two angry serpents with wings; they are pulling a chariot.

343

From the Eleusian cult we inherit a depiction of Triptolemus in a chariot being pulled on the Nile by two strong serpents.

344

A unique example of iconography depicting a god being drawn by a creature with serpent legs or feet has been found in southern Germany. The god is none other than Jupiter. The iconography develops out of the myth of the Giants. Jupiter is sometimes shown on his horse trampling a Giant. In other stone sculptures Jupiter is depicted being pulled along by a Giant. Sometimes a Giant elevates the horses of Jupiter with his hands or his serpentine feet. On occasion, Jupiter’s horses and chariot are swept into the sky by the heads of the serpents.

345

The symbolic meaning of this iconography is represented by the verbs “elevate” and “swept.” The massive stone showing the serpent heads pushing upward on the lower chest of the horses adds to the impression. Jupiter soars heavenward, employing the mighty anguiepede Giants, and the power emanates from the serpents.

The same anguine symbolism is celebrated in the Orphic hymns. In particular, note the hymn to the Eleusinian Demeter. While Aphrodite’s chariot is drawn by swans (55.20), the hymn to Demeter describes a chariot drawn by serpents (or dragon-serpents): “You yoke your chariot to bridled serpents” (40.14).

While the imagery of winged serpents drawing chariots is odd to us, it was far from uncommon in antiquity, as we have already seen.

346

Herodotus influenced many Greeks and Romans in believing in the reality of such mythology when he reported the existence of large serpents and serpents with wings. He wrote that in the western sections of Libya are found monstrous serpents [4.191]).

[4.191]).

347

He reports to have seen in Thebes “sacred serpents” . He proceeds to Buto and then further deep into Arabia to learn about “winged serpents”

. He proceeds to Buto and then further deep into Arabia to learn about “winged serpents”

. His belief in the existence of such creatures was bolstered by what he saw and heard: lots of dead bones and the claims of the natives.

. His belief in the existence of such creatures was bolstered by what he saw and heard: lots of dead bones and the claims of the natives.

348

Herodotus also describes “small winged snakes of many colors” in the spice-bearing trees that only in Arabia produce frankincense and myrrh and other precious spices

in the spice-bearing trees that only in Arabia produce frankincense and myrrh and other precious spices

(Hist.

3.107). Herodotus also believes that vipers and winged serpents are not plentiful because the female bites off the neck of the male during copulation and then (as in retribution) the young eat their way through their mother’s womb, killing her also (

Hist.

3.109). Perhaps it was easier for the ancients to believe in flying serpents of great size because they, like us, have seen fish rise out of the sea and fly for something like a hundred yards. When scuba diving off the coast of southeast Florida, I remember seeing flying fish shoot out of the water and skim speedily ahead of the boat, about 1.5 meters above the surface.