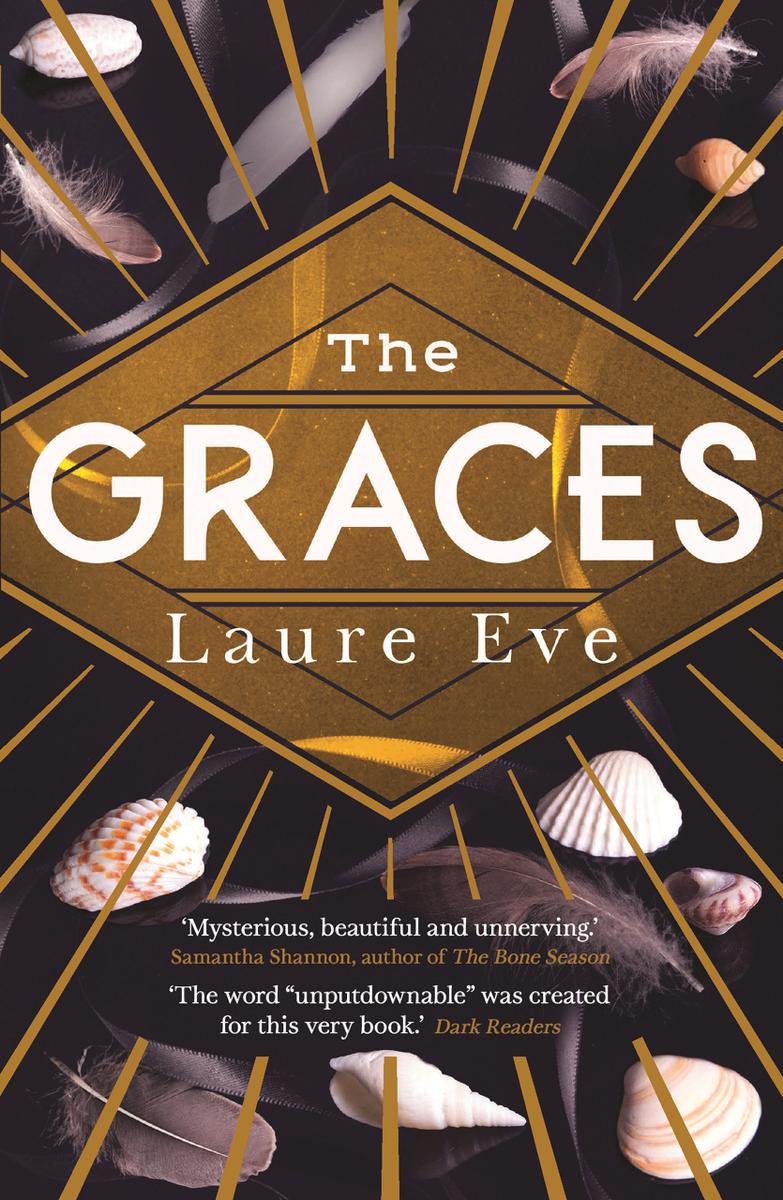

The Graces

Authors: Laure Eve

Praise for

THE

GRACES

‘Fabulously dark and addictive.’

Bookseller

‘The ending will make readers want to read the entire novel again … Though the facts may be slippery, the prose never is; it’s precise, vivid, and immediate. Powerful.’

Kirkus

‘Mysterious, beautiful and unnerving,

The Graces,

like its titular family, will keep you enthralled from beginning to end.’ Samantha Shannon, NYT bestselling author of

The Bone Season

‘As intricate and deadly as a spider’s web.

The Graces

will draw you in, with no guarantee of letting you go. It’s powerful, deadly, chilling and compelling. It is a masterpiece.’ Melinda Salisbury, author of

The Sin Eater’s Daughter

‘Laure Eve breathes new life into witches. Thrilling, dark and atmospheric

The Graces

will hold you spellbound from start to finish.’

Jess Hearts Books

‘Appropriately for a book about a family said to be witches,

The Graces

is absolutely spellbinding!’

YA Yeah Yeah

‘

The Graces

is one of those books that you finish and think, damn, I wish I’d written that. Without a doubt, this is one of my favourite books of 2016.’

The Mile Long Bookshelf

‘Enthralling, thrilling and beautiful, I believe the word “unputdownable” was created for this very book.’

Dark Readers

‘

The Graces

is absolutely incredible!’

Once Upon a Bookcase

‘A wickedly dark page-turner that will keep you gripped from start to finish.’

Writing from the Tub

‘This is it. This is one of those books that you’re going to trade endlessly with your friends and ask them “did you get to the twist yet? You won’t BELIEVE IT.”’

Reading in Between the Lines

‘This book is a story of obsession and you’ll be reading

The Graces

obsessively until the end.’

Luna’s Little Library

‘There is magic in here, but also the allure of celebrity and glamour – until you discover that these are insubstantial and slippery things themselves.’

MinervaReads

‘Intense, fascinating and deliciously devilish.

The Graces

is gold waiting to be discovered.’

Sisterspooky

‘An enchanting mystery that is absolutely captivating and hauntingly alluring!’

Creative In The Arts

‘Be prepared for a heart ripping twist. Fenrin & River nearly broke me!’

Serendipity Reviews

GRACES

L

AURE

E

VE

- Title Page

-

- Part 1

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

-

- Part 2

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- Chapter 36

- Chapter 37

-

- Acknowledgements

- Graces sequel ad

- Rebel of the Sands Ad

- Rebel of the Sands Extract

- Rebel of the Sands ebook link

- The Monstrous Child Ad

- Highly Illogical Behaviour Ad

- About the Author

- Copyright

Everyone said they were witches.

I desperately wanted to believe it. I’d only been at this school a couple of months, but I saw how it was. They moved through the corridors like sleek fish, ripples in their wake, stares following their backs and their hair. Their year groups had grown used to it by now, or at least pretended they had, and tried their hardest to look bored by it all. But the younger kids hadn’t yet learned how to hide their silly dog eyes, their glamoured, naked expressions.

Summer Grace, the youngest, was fifteen and in my year. She backchatted the teachers no one else dared to, her voice drawling with just the right amount of rude to make it clear she was rebelling, but not enough to get her into serious trouble. Her light Grace hair was dyed jet black and her eyes were always ringed in black kohl and masses of eye shadow. She

wore skinny jeans and boots with buckles or Victorian laces. Her fingers were covered in thick silver rings and she always had on at least two necklaces. She thought pop music was ‘the devil’s work’ – always said with a sarcastic smile – and if she caught you talking about boy bands, she’d slay you for it. The worst thing was, everyone else joined in, even the people you’d been excitedly discussing the band with not three seconds before. Because she was a Grace.

Thalia and Fenrin Grace, at seventeen, were the eldest. Non-identical twins, though you could see the family resemblance. Thalia was slim and limber and willowed, her fine-boned wrists accentuated by fistfuls of tinkling bangles. She had a tight coil of coarse, caramel-colored strands permanently woven round a thick lock of her honey hair. She wore her hair loose, rippling across her shoulders, or pulled carelessly into a topknot from which tendrils always slid out to wisp around her neck. She wore long skirts with delicate beadwork and rows of tiny mirrors sewn onto the hem, thin open-necked tops that floated against her skin, fringed scarves with metallic threading slung around her hips. Some of the girls tried to copy her, but they always looked as if they were wearing a gypsy costume to school, which got them no end of grief, and then they never wore them again. Even I hadn’t been able

to resist trying something like it, just once, when I first came here. I’d looked like an idiot. Thalia just seemed like she was born in those clothes.

And then there was Fenrin.

Fenrin.

Fenrin Grace. Even his name sounded mythical, like he was more creature than boy. He was the school Pan. Blonder than his twin, Thalia, he let his hair grow loose and floppy over his forehead. He wore white muslin shirts a lot and leather cords wrapped round his wrists. A varnished turret shell dangled from a leather thong around his neck every day. He never seemed to take it off. The weight of it rested against his chest, a perfect V. He was lean, lean. His smile was arrogant and lazy.

And I was completely and utterly in love with him.

It was the stupidest, most obvious thing I could have done, and I hated myself for it. Every girl with eyes loved Fenrin. But I was not like those prattling, chattering things with their careful head tosses and thick, cloying lip gloss. Inside, buried down deep where no one could see it, was the core of me, burning endlessly, coal black and coal bright.

The Graces had friends, but then they didn’t. Once in a while, they would descend on someone they’d never hung out with before, making them theirs

for a time, but a time was usually all it was. They changed friends like some people changed hairstyles, as if perpetually waiting for someone better to come along. They never went out drinking in the pubs at the weekends, never went to the Wednesday student night in the local club like everyone else. The rumour was that they were barely allowed to leave their house, except to come to school.

No one had real details of their personal lives – except for whoever Fenrin was sleeping with in any given week, as he never hid it. He’d tour the girl around school for however long it lasted, one arm slung over her shoulders in a lazy fashion, and she would drip off him, giggling madly and dying with happiness. I’d never seen one of these girls around him longer than a month or two. They were nothing, just distractions. He was waiting for someone special, someone different who would catch his attention so suddenly and so completely, he’d wonder how he had survived all this time without them. They all were, all three of them. I could see it.

All I had to do was find a way to show them it was me they’d been waiting for.

At first, I’d thought moving to this town was punishment for what I’d done.

It was miles from where I’d grown up, and I’d never even heard of it before we came here. My mother had spent a couple of holidays here as a child and had somehow decided that this tiny, old coastal town caught between the sea and acres of wilds was exactly the right kind of place to move on with our lives after the last few awful months. Dunes, woods and moors peppered with standing stones crawled across the landscape, surrounding the place like a barrier. I’d come from a cement suburb rammed with corner shops, furniture warehouses and hairdressers. The closest thing to nature we’d had there was the council-maintained flowerbeds in the high street. Here, it was hard to forget what really birthed you. Nature was the thing you walked on and breathed in.

Before the Graces noticed me, I was the quiet one who stuck to the back corners of places and tried not to draw attention. A couple of other people had been friendly enough when I’d first arrived – we’d hung out a little and they’d given me a crash course in how things ran here. But they got tired of the way I wrapped myself up tight so no one could see inside me, and I got tired of the way they all talked about things I couldn’t even muster up fake enthusiasm for, like getting laid and partying and TV shows about people getting laid and partying.

The Graces were different.

When I’d been told they were witches, I’d laughed in disbelief, thinking it was time for a round of ‘lie to the new girl, see if she’ll swallow it’. But although some people rolled their eyes, you could see that everyone, underneath the cynicism, thought it could be true. There was something about the Graces. They were one step removed from the rest of the school, minor celebrities with mystery wrapped around them like fur stoles, an ethereal air to their presence that whispered tantalisingly of magic.

But I needed to know for sure.

*

I’d spent some time trying to work out their angle, the one thing I could do that would get me on their radar.

I could be unusually pretty, which I wasn’t. I could be friends with their friends, which I wasn’t – no one I’d met so far was in their inner circle. I could be into surfing, the top preoccupation of anyone remotely cool around here, but I’d never even tried it before and would likely be embarrassingly bad. I could be loud, but loud people burned out quickly – everyone got bored of them. So when I first arrived, I did nothing and tried to get by. My problem was that I tended to really think things through. Sometimes they’d paralyse me, the ‘what ifs’ of action, and I didn’t do anything at all because it was safer. I was afraid of what could happen if I let it.

But on the day they noticed me, I was acting on pure instinct, which was how I knew afterwards that it was right. See, real witches would be tuned in to the secret rhythm of the universe. They wouldn’t mathematically weigh and counterweigh every possible option because creatures of magic don’t do that. They weren’t afraid of surrendering themselves. They had the courage to be different, and they never cared what people thought. It just wasn’t important to them.

I wanted so much to be like that.

It was lunch break, and a rare slice of spring warmth had driven everyone outdoors. The field was still wet from last night’s rain, so we were all squeezed

onto the hard courts. The boys played football. The girls sat on the low wall at one end, or stretched their bare legs out on the tarmac and leaned their backs against the chain-link fence, talking and squealing and texting.

Fenrin’s current crowd was kicking a ball about, and he joined in halfheartedly, stopping every so often to talk to a girl who had run up to him, his grin wide and easy. He shone in the crowd like a beacon, among them all but separated, willingly. He played with them and hung out with them and laughed with them just fine, but something about his manner told me that he held the true part of himself back.

That was the part that interested me the most.

I got to the wall early and opened my book, hoping I looked self-sufficiently cool and reserved, rather than sad and alone. I didn’t know if he’d seen me. I didn’t look up. Looking up would make it obvious I was faking.

Twenty minutes in and one of the football guys, whose name was Danny but who everyone called Dannyboy like it was one name, was flirting with an especially loud, giggly girl called Niral by booting the ball at her section of the wall and making her scream every time it bounced past. The more he did it, the more I saw his friends roll their eyes behind his back.

Niral didn’t like me. Which was strange because everyone else left me alone once they’d established that

I was dull. But I’d caught her staring at me a few times, as if something about my face offended her. I wondered what it was she saw. We’d never even exchanged a word.

I’d looked up the meaning of her name once. It meant ‘calm’. Life was full of little ironies. She wore big, fake gold hoop earrings and tiny skirts, and her voice had a rattling screech to it, like a magpie’s. I’d seen her with her parents in town before. Her plump little mother wore beautiful saris and wove her long hair in a plait. Niral cut her hair short and shaved it on one side. She didn’t like what she was from.

Niral also didn’t like this timid girl called Anna, who looked like a doll with her tight black curls and big dark eyes. Niral enjoyed teasing people, and her voice always got this vicious sneer to it when she did. Anna, her favourite target, was sat on the wall a little way down from me. Niral had come out to the hard courts with a friend, looked around a moment and then chose to sit right next to Anna, whose tiny child body had tensed up while she hunched even closer to her phone.

I had English and maths with Niral, and she seemed pretty ordinary. Maybe she was loud because part of her knew this. She didn’t seem to like people she couldn’t immediately understand. Anna was quiet and childlike, a natural target. Niral liked to tell people that Anna was a lesbian. She never said ‘gay’ but ‘lesbian’ in

a drawling voice that emphasised each syllable. Anna must have had skin made of glue because she couldn’t take any little jibes. They didn’t roll off her – they stuck to her in thick, glowing folds. Niral was whispering and pointing, and Anna was curling over as if she wanted to crawl into her own stomach.

Then Dannyboy joined in, hoping to impress Niral. He booted the football over to Anna with admirable precision, smacking it into her hands and knocking her phone from them. It smashed to the ground with a flat crack sound.

Dannyboy ambled over. ‘Sorry,’ he said, offhand, but his eyes were on Niral.

Anna ducked her head down. Her black curls dangled next to her cheeks. She didn’t know what to do. If she went for the phone, they might carry on at her. If she stayed there, they might take her phone and try to continue the game.

I watched all this over the top of my book.

I really hated that kind of casual bullying that people ignored because it was just easier – I’d been on the end of it before. I watched the ball as it rolled slowly to me, banging against my foot. I stood, clutching it, and instead of pitching it back to him, I threw it the opposite way, onto the field. It bounced off along the wet grass.

‘What did you do that for?’ said another boy, angrily. I didn’t know his name – he didn’t hang out with Fenrin. Dannyboy and Niral looked at me as one.

Fenrin was watching. I saw his golden silhouette stop out of the corner of my eye.

‘God, I’m sorry,’ I said. ‘I kind of thought those two might want to be alone for a while instead of nauseating the rest of us.’

There was a crushing silence.

Then the angry boy started to laugh. ‘Dannyboy, take your girlfriend and get the ball, man. And we’ll see you in, like, a couple of hours.’

Dannyboy shuffled uncomfortably.

‘There’s the copse at the back of the field,’ I commented. ‘Nice and secluded.’

‘You stupid bitch,’ said Niral to me.

‘Maybe don’t give it out,’ I replied quietly, ‘if you can’t take it.’

‘New girl’s got a point,’ said the angry boy.

Niral sat still for a moment, trying to decide what to do. The tide had turned against her.

‘Come on,’ she said to her friend. They gathered their bags and their makeup and their phones and walked off.

Dannyboy didn’t dare look after her – the angry guy was still ribbing him. He went back to playing

football. Anna retrieved her phone and pretended to text, her fingers tapping a nonsensical rhythm. I nearly missed her almost-whisper. ‘Thought the screen was cracked right through. Looked broke.’

She didn’t thank me or even look up. I was glad. I was at least as awkward as she was, and both of us awkwarding at each other would have been too much for me. I sat back down next to her, buried my face in my book and waited for my pulse to stop its erratic drumming.

When the bell rang, I shouldered my bag, and then and there made my bold ploy. Without thinking about it I walked up to Fenrin, as if I were going to talk to him. I felt his eyes on me as I approached, his curiosity. Instead of following it up with words, though, I kept walking past. At the last moment my eyes lifted to his, and before my face could start its tragic burn, I gave him an eyebrow raise. It meant,

what can you do?

It meant,

yeah I see you, and so?

It meant,

I’m not too bothered about talking to you, but I’m not ignoring you either because that would be just a little bit too studied.

I lowered my gaze and carried on.

‘Hey,’ he called behind me.

I stopped. My heart beat its fists furiously against my ribs. He was a few feet away.

‘Defender of the weak,’ he said with a grin. His first ever words to me.

‘I just don’t like bullies so much,’ I replied.

‘You can be our resident superhero. Save the innocent. Wear a cape.’

I offered him a smile, a wry twist of the mouth. ‘I’m not nice enough to be a superhero.’

‘No? Are you trying to tell me you’re the villain?’

I paused, wondering how to answer. ‘I don’t think anyone is as black and white as that. Including you.’

His grin widened. ‘Me?’

‘Yeah. I think sometimes you must get bored of how much everyone worships you, when maybe they don’t even know the real you. Maybe the real you is darker than the one you show the world.’

The set of his mouth froze. Another me from another time recoiled in horror at my recklessness. People didn’t like it when I said things like this.

‘Huh,’ he said, thoughtfully. ‘Not out to make friends, are you.’

Inside, I shrivelled. I’d blown it. ‘I guess … I’m just looking for the right ones,’ I said. ‘The ones who feel like I do. That’s all.’

I’d told myself I wouldn’t do this any more. They didn’t know me here – I could be a new me, the 2.0 version, now with improved social skills.

Stop talking. Stop talking. Walk away before you make it worse.

‘And how

do

you feel?’ he asked me. His voice wasn’t teasing. He seemed curious.

Well, I might as well go out with a bang.

‘Like I need to find the truth of the world,’ I said. ‘Like there’s more than this.’ I raised a hand helplessly to the grey school building looming over us. ‘More than just …

this

, this life, every day, on and on, until I’m dead. There’s got to be. I want to find it. I

need

to find it.’

His eyes had clouded over. I thought I knew that look – it was the careful face you made around crazy people.

I sighed. ‘I have to go. Sorry if I offended you.’

He said nothing as I walked away.

I’d just exposed my soul to the most popular boy in school, and in return he’d given me silence.

Maybe I could persuade my mother to move towns again.

*

It was raining the next day, so I ate my lunch in the library. I was alone – the friendly girls I’d hung out with when I’d first arrived never asked me to sit with them in the cafeteria any more, and I was glad to have the time to read more of my book before class. It was

too cold to go outside, and Mr Jarvis, the librarian, was nowhere to be seen, so I put my bag on the table and opened my Tupperware behind it. Cold beans on toast with melted cheese on top. A bit slimy, but cheap to buy and easy to make, two important factors in my house.

I took out my lunch fork, the only one in our cutlery drawer that didn’t look as though it came from a plastic picnic set. It was a thick kind of creamy-coloured silver and had this flattened plate of scrollwork on the handle bottom. I washed it every night and took it back to school with me every day. It made me feel a bit more special when I used it, like I wasn’t just some scruff, and my mother never noticed it was missing.

I’d worried about my conversation with Fenrin that whole day and well into the night, turning my words over again and again, wondering what I could have done better. In my mind, my voice was even and measured, a beautiful cadence that positioned itself perfectly between drawling and musical. But in reality, I had an awkward town accent I couldn’t quite shift, all hard edges and soft, dopey burrs. I wondered if he’d heard it. I wondered if he’d judged me because of it.

I ate and read my book, this particular kind of fantasy novel that I secretly loved. It was my favourite

thing to do – eat and read. The world just shut up for a while. I’d just got to the bit where Princess Mar’a’tha had shot an arrow into one of the demon horde attacking the royal hunting camp, and then I felt it.

Him. I felt him.

I looked up into his face, which was tilted down at my shit, embarrassing book and my shit, embarrassing lunch.

‘Am I interrupting?’ said Fenrin. A long wave of his sungold-tipped hair had slipped from behind his ear and hung by his cheekbone. I actually caught a waft of him. He smelled like a thicker, manlier kind of vanilla. His skin was lightly tanned.

I hadn’t lowered my fork; I just looked at him dumbly over it.

It worked. I told him the truth and it worked.

‘Eating in the library again, when the rest of the school uses the cafeteria,’ he mused. ‘You must enjoy being alone.’