The Great Depression in United States History (4 page)

Read The Great Depression in United States History Online

Authors: David K. Fremon

As more and more people were put out of work, fewer and fewer believed him. Even the Federal Reserve Board cautioned Hoover, “It will take perhaps months before readjustment is accomplished.”

14

Hoover did take actions to ease the financial crisis. Soon after the Crash, he met with business leaders. The president asked them not to cut workers’ pay. At first, many went along with the request. But as conditions kept getting worse, most could not keep their promises. Some cut wages. Others laid off employees instead of slashing wages. Others demanded increased production, which meant more work for the same pay from their workers.

Yet Hoover hesitated to use the federal government’s powers to halt the economic decline. He felt that state governments, local governments, and private charities should do that work. Yet these groups were strapped for money. They could not carry the burden of lifting the nation.

Hoover refused to consider financial relief for individuals. Part of this opposition came from personal beliefs that men and women lost their dignity if the government gave them a handout.

Big businesses also opposed relief. Their money provided the core of Hoover’s election support, and he would not desert them. Millionaire Andrew Mellon served as secretary of the treasury under Hoover’s predecessors Harding and Coolidge. Mellon worked mainly to cut taxes for the wealthiest Americans. Hoover had little use for Mellon. But he kept him as treasury secretary anyway, because he feared criticism from the business community if he did otherwise.

That fear of opposition also made him sign the Smoot-Hawley bill in 1930. Economist Paul Douglas gave Hoover a petition with signatures of one hundred economists who opposed the bill. Automobile magnate Henry Ford called the Smoot-Hawley bill “an economic stupidity.”

15

Hoover signed it anyway.

This law created the highest tariff (tax on imported goods) in American history. Republican Congress members who had proposed the bill hoped that high prices of foreign goods would force Americans to buy American-made products. Instead, other countries imposed their own high tariffs. These taxes kept American companies from selling their goods abroad.

Hoover made one critical move to free up European money. In 1931, he proposed a one-year moratorium (halt) on World War I debts. He hoped debtor nations would use that money to buy American consumer goods. Germany instead used the money saved to build up its military forces.

The average American could not identify with the wealthy, aloof Hoover. Most Americans felt he could not identify with them. Even when Hoover tried a humanitarian gesture, it met with protests. When the president appropriated money to the Department of Agriculture for feed for livestock, thousands complained. Why was he willing to feed their animals but not their children?

Hoover’s most driving program, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), gained little popular support. It allowed the president to lend more than $500 million to ailing banks, railroads, and insurance companies.

The RFC ran into problems almost immediately. Central Republic Bank of Chicago received a $90 million loan under the program. Charles G. Dawes, director of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, was also a director of the bank. Dawes soon resigned from the RFC, and no one accused either Dawes or the bank of wrongdoing. But the incident gave Democrats ammunition in their campaign against Hoover. Here was a president who could not find money to help struggling teachers or unemployed miners, yet he created a program to help rich banker friends.

On July 8, 1932, the stock market bottomed out. The Dow Jones average, which had reached 452 in September 1929, fell to a sickly 58. U.S. Steel had fallen from $262 to $22 a share. Montgomery Ward had plummeted from $183 to $4. General Motors had dived from $73 to $8.

Critics joked that Hoover’s policy of “rugged individualism” was actually one of “ragged individualism.”

16

Wherever the president went, he found signs that read “In Hoover we trusted—now we are busted.”

17

During an appearance in West Virginia, a military guard gave him the traditional twenty-one-gun salute. Someone in the audience muttered, “By gum, they missed him.”

18

Bonus March

Walter L. Waters needed money in 1932. One day that summer, the unemployed World War I veteran had an idea. The government had passed a bill promising war veterans a cash bonus in 1945. Why not give out that bonus now? Waters and neighboring veterans set out from Portland, Oregon, to Washington, D.C., to make his point.

These vets were part of the Allied Expeditionary Force that had helped win the war. Soon news of Waters’s “Bonus Expeditionary Force” spread across the country. Thousands of men and many of their families joined him in a trip to Washington. By July, some twenty thousand “bonus marchers” and family members descended upon the nation’s capital.

Many of the marchers took over abandoned buildings on Pennsylvania Avenue. Most, however, settled across from the Capitol along the Potomac River. The Anacostia Mud Flats, now housing the Bonus Expeditionary Force, became America’s largest Hooverville. Pelham Glassford, the District of Columbia chief of police, sympathized with the marchers. He persuaded the Army to loan them tents and cots.

Others were not so sympathetic. Herbert Hoover opposed the immediate bonus. Congress debated the idea. While the House of Representatives and Senate discussed the measure, the bonus marchers waited. They demonstrated for the bill, but the demonstrations were peaceful.

The House passed a bonus bill in July. The Senate, however, turned down the measure. Most marchers, when they heard of the bill’s failure, returned home. More than eight thousand six hundred stayed in Washington, D.C. They showed no signs of leaving.

To Hoover, they were an embarrassment. Yet he at first refused to force them from their temporary homes. Others, including General Douglas MacArthur, saw them as a danger.

Hoover finally listened to MacArthur’s advice. He ordered the police to evict the marchers from the abandoned buildings. The police moved on the morning of July 28. Around noon, someone threw a brick at a police officer. The police reacted by firing at innocent marchers. Two hours later, two marchers lay dead.

Later that afternoon, MacArthur led troops down Pennsylvania Avenue. At first some veterans cheered the soldiers. They thought the troops were there to help them. They soon learned otherwise.

Hoover did not order MacArthur to rout the Anacostia squatters. The general did so anyway. His troops scattered the marchers with swords, tear gas, and bayonets. Their horses trampled women and children. Then the soldiers set fire to the campsite. Dwight Eisenhower, who served under MacArthur, called it “a pitiful scene.”

19

Hoover declared, “Thank God we still have a government that knows how to deal with a mob.”

20

The veterans who limped home, their wives, children, and friends thought otherwise. The president was no longer an object of ridicule. He was an object of hatred.

Lame Ducks

The Bonus March fiasco sealed an already doomed election.

Republicans nominated Herbert Hoover even though his defeat was certain. They would be admitting their failure by not backing their president. And no other Republican wanted to face a humiliating loss.

Hoover lost in November. It was the most one-sided election since 1864. Franklin D. Roosevelt won the election—the same man who had praised Hoover only twelve years earlier.

The Republican Party lost the presidency, both houses of Congress, and the confidence of the American people. They were truly “lame ducks,” defeated politicians waiting until their terms expired.

The economy, however, did not sit idly. Things only got worse in the winter of 1932–33. By March 1933, about nine thousand banks had failed, wiping out the savings of millions of Americans.

A new bank panic began in February 1933. On February 14, worried investors made massive withdrawals from Detroit banks. Michigan’s governor called a “bank holiday”—closing all banks until further notice.

Ten days later, customers made panicked withdrawals from Baltimore banks. This led to a bank holiday in Maryland. Similar actions took place in other states during the next two weeks.

March 4, 1933, was Inauguration Day. Hoover would leave the White House and Roosevelt would enter it. Governors of New York and Illinois called bank holidays at dawn. They feared runs at the major banking centers of New York City and Chicago.

A worn out and weary Herbert Hoover rode to the inaugural site. He told an aide, “We are at the end of our string. There is nothing more we can do.”

21

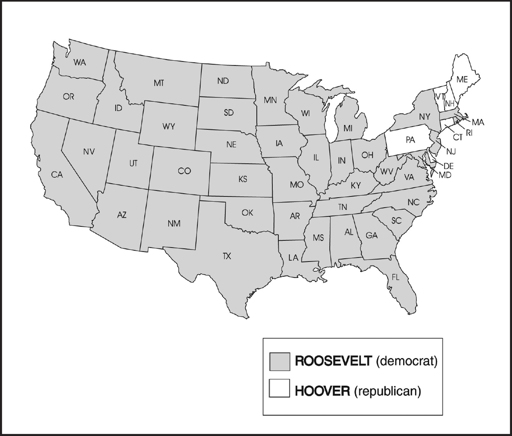

1932 Presidential Election

Image Credit: Enslow Publishers, Inc.

Franklin D. Roosevelt scored an incredible victory in the 1932 presidential election. Herbert Hoover beat the Democrat in only six eastern states—Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Delaware.

On Inauguration Day, 1933, America faced a national crisis. Thousands of banks had gone out of business, and millions of workers were unemployed. It would take an extraordinary leader to guide the country from economic ruin. America found such a hero, but he was an unlikely one.

Young FDR

If anyone was “born with a silver spoon in his mouth,” it was Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His family had wealth. It was not the newly acquired wealth of capitalists. Instead, it was the wealth of American aristocracy. Young Franklin had twelve ancestors who came to America on the

Mayflower

and others who were among European royalty. Distant relatives included eleven former United States presidents. Neighbors along New York’s Hudson River Valley had known and respected the Roosevelts for generations.

Roosevelt’s father James and mother Sara rejoiced at the birth of their son in 1882. Franklin Roosevelt grew up happy, safe, and more than a little spoiled. By the time he was sixteen years old, he had visited Europe eight times.

Franklin attended Harvard, where he was known more for his yachting skills than his grades. At Harvard, he fell in love with the woman who became his wife.

Some people say that opposites attract. That seemed to be the case with Franklin Roosevelt. Young, handsome, and wealthy Franklin Roosevelt could have dated many women. His fourth cousin, Eleanor Roosevelt, was a plain, shy orphan. Yet she had qualities that attracted him. He admired her intellectual abilities. She also showed great concern for other, less fortunate people.

Franklin idolized Eleanor’s uncle, former president Theodore Roosevelt. When Eleanor and Franklin were married in 1905, Theodore (who was Franklin’s fifth cousin) gave the bride away. Franklin was aware of Theodore’s career path—New York state assembly, assistant secretary of the Navy, governor of New York, president. He followed a similar one.

Sunrise at Campobello

Roosevelt’s state senate district was wealthy and overwhelmingly Republican. Even the most loyal Democrats gave him little chance of winning when he ran in the 1910 election. But Franklin Roosevelt, a Democrat, refused to listen to scoffers. He toured the district in his red car, shook as many hands as possible, and squeezed out a narrow victory.

Franklin supported Woodrow Wilson for president in 1912. The new chief executive rewarded Roosevelt by making him assistant secretary of the Navy. By most accounts, he was a hard-working administrator. But skills in the Cabinet do not always mean election victories. Roosevelt was trounced in a 1914 Senate election. Six years later, he ran for vice president with James M. Cox. Republicans Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge defeated Cox and Roosevelt. “It wasn’t a landslide,” noted Joseph Tumulty, President Wilson’s private secretary. “It was an earthquake.”

1

Even with the loss, Franklin Roosevelt’s political future appeared bright. Voters throughout the country now knew him. His possibilities appeared limitless—until one summer day in 1921.

The Roosevelts were vacationing at their summer home at Campobello, New Brunswick, in Canada. It was a typical busy day for the active Franklin Roosevelt. He sailed with his sons, fought a small forest fire, then refreshed himself with a swim in the cold ocean water.