The History Buff's Guide to World War II (21 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

MOST SIGNIFICANT BATTLES: EUROPE AND NORTH AFRICA

Importance is in the eye of the beholder. In the early 1980s, a television documentary about the eastern front aired internationally. The program was titled “The Great Patriotic War” for Russian viewers, “The Unforgettable War” for West Germans, and “The Unknown War” for U.S. audiences.

77

When thinking of World War II, Americans generally focus on England and Normandy, placing all other areas a distant second. The tendency is understandable. Of the five million American troops sent overseas, most served in Britain and France. The United States was simply closer to the Old World than to the East, geographically, politically, and historically. The dominant language in the United States was and remains English.

Of course, Western Europe was only a part of the picture. A state of war existed in North Africa for nearly a decade. Most of the fighting and dying happened east of Berlin. Compared to the duration of combat in France, Americans fought twice as long in Italy and four times as long in the skies over Germany.

As reflected by the following list, the war was truly global. Below are the ten most significant military engagements in Europe and North Africa, listed in chronological order and selected for their respective military and political consequences for the entire hemisphere.

1

. POLAND (SEPTEMBER 1–OCTOBER 6, 1939)

France and Britain did not declare war when Germany annexed Austria in 1938 or marched into Prague in 1939, but they drew the line when Hitler made threatening demands for Polish territory. It hardly mattered.

Fixated on demonstrating his military might, Hitler intended to take Poland by force. With all risk of Russian intervention eliminated by the unsavory Nazi-Soviet Pact signed a week earlier, the German Wehrmacht slipped its hand around Poland, with the navy in the Baltic to the north, two armies to the northwest, three to the southwest, and one to the south in Slovakia. In the morning darkness of September 1, the hand closed.

Committed to holding the highly populated west, the Polish military lost unity within hours. Luftwaffe dive bombers severed lines of communication, and tank brigades split armies into isolated pockets. Defending tenaciously, the Poles managed only one successful assault, when two German divisions attempted to cut off the retreat of an entire Polish army. Any chance of survival disappeared when the Soviets attacked from the east on September 17. Fighting officially ended on October 5.

Partitioned for the fourth time in two centuries, Poland suffered nearly 100,000 military and civilian casualties, a fraction of the 5.5 million it would eventually lose in the war. British and French promises of military intervention never materialized. The Polish government escaped and found exile in London, only to be compromised years later during Allied conferences. Citizens who survived went on to endure a lifetime of occupation, five years under the Nazis, and more than forty under the Soviets.

Blitzkrieg was only the beginning of a six-year war in Poland.

The Poles may have surrendered in five weeks, but they put up a harrowing fight. Germany lost more dead conquering Poland than the United States would later lose taking Iwo Jima.

2

. FRANCE (MAY 10–JUNE 22, 1940)

Of the six countries Hitler rapidly invaded and conquered in the spring of 1940, five were targeted for their geographic location. Hitler had to invade the Nordic countries of Denmark and Norway, he reasoned, to protect Germany’s northern border and access the Atlantic. Luxembourg, Belgium, and Holland were simply in the way of his only true adversary in the West.

As Hitler contended in

Mein Kampf

, “France is and will remain the implacable enemy of Germany.” Noting France’s stubborn survival during the First World War, imposing reparations, and occupying the Rhineland against international will: “What France has always desired, and will continue to desire, is to prevent Germany from becoming a homogenous Power.”

78

More accurately, France simply did not want Germany to invade again, having involuntarily hosted the Huns in 1870 and 1914. Many credited this fearful and defensive posture as one of the main reasons the country fell so quickly in 1940.

Militarily, France was the zenith of Hitler’s success. Never before and never again would Nazi Germany conquer a country of comparable wealth and military size. The improbable and rapid victory also gave Germany submarine pens along the Atlantic, large amounts of cash indemnities, coal and bauxite deposits, and a base for future aircraft and missile operations against Great Britain.

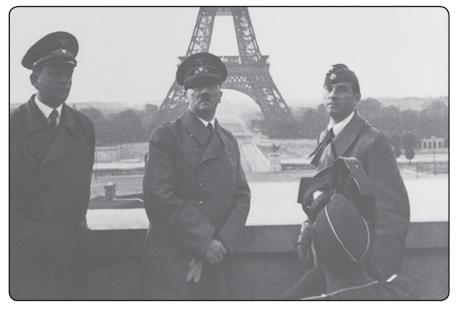

Hitler celebrated the fall of France with a well-documented tour of Paris.

To further humiliate the defeated French, Hitler stipulated that the surrender proceedings take place in a historic railway coach in Compiègne, the same railcar in which Germany signed the armistice of surrender to end the First World War.

3

. THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN (JULY 10–SEPTEMBER 17, 1940)

When Hitler’s “Nordic cousins” rejected his appeal for a peace agreement after the fall of France, he intended to teach them a lesson: “Since England, despite its hopeless military position, still shows no signs of willingness to come to terms, I have decided to prepare a landing operation against England and if necessary to carry it out.”

79

Invasion first required control of the air. The Luftwaffe promised to deliver, calculating it would take a mere four days to obliterate the RAF’s fighter command.

80

The ensuing battle uncovered several German oversights. Their twin-engine bombers—Heinkel 111s and Junkers 88s—were slow and easy targets with modest payloads. The Stuka JU-87 dive bomber, though menacing with its whaling siren, had the speed of a crop duster. The Messerschmitt 109 was an excellent fighter, but its fuel capacity barely got it to London and back. Yet the weakest aspect of the Luftwaffe was strategy. Bombing ports and ships, followed by airstrips and finally cities, the German air force never eliminated the British radar sites.

Outnumbered four to one, British fighters were able to survive by pinpointing their efforts with an early warning system. In just over two months, the RAF lost 1,100 aircraft to the Germans’ 1,800. Thanks to rescue operations on their home turf, though, the British only lost 550 pilots compared to 2,500 German crewmen. On September 17, 1940, Hitler postponed the invasion of Britain indefinitely, choosing instead to punish Britain by way of “the Blitz”—nightly air raids that would last until May 1941 and kill more than 40,000.

The Battle of Britain was numerically an intermediate affair. Both sides replaced their material and crew losses quickly. Britain’s resolve fueled a great deal of national pride and a considerable amount of American admiration. Ironically, Germany may have also benefited. Hitler lacked the landing vessels and warships to mount an amphibious assault in force. Any Nazi flotilla likely would have succumbed to an immensely superior British navy.

81

St. Paul’s Cathedral provides a background for a December 1940 bombing of London.

The Battle of Britain was an international fight. RAF pilots included volunteers from Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czechoslovakia, France, Ireland, Jamaica, New Zealand, Palestine, Poland, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), South Africa, and the United States.

4

. BARBAROSSA (JUNE 22, 1941)

The largest invasion of all time, ten times larger than D-day, the Third Reich offensive into the Soviet Union instantly and completely altered the course of the war. It revealed the absolute limits of blitzkrieg, opened the bloodiest theater of the war, and broke the Nazi-Soviet alliance.

The attack began at 3:00 a.m. June 22, 1941. The front stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea, a span of more than a thousand miles. Amassed were more than a million horses and vehicles. Three-fourths of the German armed forces—plus divisions from Finland, Hungary, and Romania—totaled nearly four million men. In a letter to his confidante Benito Mussolini, Hitler called the order to launch Operation Barbarossa the hardest decision of his life: “We have no chance of eliminating America. But it does lie in our power to exclude Russia.”

82

Hitler was optimistic. Thinking he could “crush Soviet Russia in a quick campaign,” he believed a short, massive assault would break the Bolshevik experiment, “and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down.” Such was his confidence that winter gear was not procured for the operation.

83

The plan, such as it was, entailed three great army groups: one to push northeast to capture Leningrad, one to head straight for Moscow, and one to progress southeast to the oil fields of the Caucasus.

At first, the blitzkrieg seemed to be working its deadly will. In six months the Soviets suffered more than 2.7 million casualties and 3.3 million captured, tolls never seen before in history. But the Soviets were able and willing to tolerate such bloodshed—and induce a fair number of deaths in return—while denying Hitler all of his objectives.

84