The History Buff's Guide to World War II (24 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

The explosion of the forward magazines of the destroyer

Shaw

produced this dramatic image of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

For all their successes, the Japanese achieved only marginal gains. Their main targets—three U.S. aircraft carriers—were not at P

EARL

H

ARBOR

. Of the seven battleships sunk or damaged, all but three were restored to full service. For the most part, docks, hangars, technicians, and engineers survived the raid, making for impressive repair times. Precious oil tanks were untouched. Above all, a previously isolationist American public abruptly became unified and belligerent, inspired all the more by a Japanese declaration of war that was delivered after the P

EARL

H

ARBOR

attack commenced.

93

So moved by the stunning success at Pearl Harbor, Japan honored the anniversary of the attack every month for the rest of the war.

3

. FALL OF SINGAPORE (FEBRUARY 15, 1942)

Winston Churchill called it the “worst disaster and largest capitulation of British history.” As far as disasters go, Britannia had suffered its share—the Norman Invasion, the Black Plague, and the battle of the Somme come to mind. But the PM was correct in the latter point. The eighty thousand Australian, Indian, Malay, and British troops captured at Singapore constituted the largest surrender in Royal military history.

94

At the tip of the Malayan peninsula, the 240-square-mile island was the British Empire’s linchpin in South Asia. The citadel stood southeast of India, southwest of Hong Kong, and northwest of Australia. Assuming the naval base would be susceptible to attack from the sea, the British constructed massive defenses and batteries along the southern coast. The dense Malay jungle to the north was believed to be impenetrable.

An hour before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan invaded “impenetrable” Malay. Battle-hardened from years of fighting in China, the Imperial Twenty-Fifth Army scored repeated routs over Commonwealth infantry, eventually forcing British commander Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival to call a retreat onto Singapore.

Though outnumbering the Japanese more than two to one, Percival did not have tanks or air support. His demoralized troops retreated farther and farther into the island, as did hundreds of thousands of refugees. Despite Churchill’s order to “fight to the end,” the defenders exhausted their supplies of food and water; yet unbeknownst to Percival, so had the Japanese. Unable to withstand a siege, Percival capitulated.

In Britain news of the surrender plunged the nation into mourning and unleashed a storm of conspiracy theories. A myth erupted that the massive coastal guns could not turn inland (they could, but their shells were only effective for piercing ship hulls). People blamed Parliament for not funding better defenses, though the government had spent many millions already. Percival was portrayed as a hero, a patsy, and an incompetent. In contrast, Japan exploded with pride. The once-mighty British Empire had been humiliated. More so than Pearl Harbor, Singapore appeared to assure ultimate victory. One newspaper headline declared: “General Situation of Pacific War Decided.”

95

Strategically, the island proved to be marginal, as it was simply bypassed in the long, gradual Allied counterthrust a year later. But psychologically it was the high tide of the war for Japan and by many accounts the beginning of the end of British imperial power in South Asia.

96

Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival lived through more than three years of imprisonment and was present at the formal Japanese surrender at Tokyo Bay. Many of his fellow captives did not survive. As many as one hundred thousand refugees caught in Singapore eventually died in Japanese captivity.

4

. MIDWAY (JUNE 3–6, 1942)

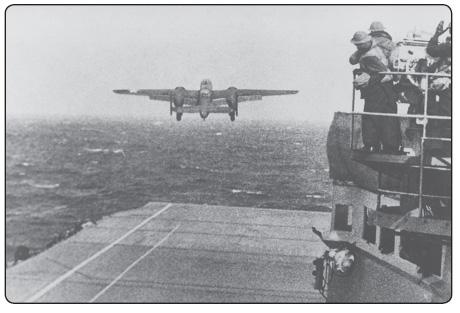

In the spring of 1942, while debating whether to invade Australia or push for India, Japan’s army and navy staff officers received a rude visit from sixteen B-25 Mitchell bombers, compliments of Col. James Doolittle and the USS

Hornet

, coming in from the central Pacific.

Bomb damage was not extensive (fifty fatalities, one hundred homes destroyed), but the attack spawned a near-unanimous decision to seize the atoll of Midway, draw U.S. carriers to the island, and destroy the Americans in a battle for the heart of the Pacific Ocean.

While sending a diversionary fleet to bite the long Aleutian tail of Alaska, Adm. Yamamoto Isoroku ordered four separate strike forces toward Midway. Thanks to

INTELLIGENCE

intercepts, Adm. C

HESTER

N

IMITIZ

was aware of Yamamoto’s intentions and moved to stop him, albeit with a smaller force including the carriers

Hornet

,

Enterprise

, and the miraculously repaired

Yorktown

, which had nearly capsized at the battle of C

ORAL

S

EA

. At first, everything went Yamamoto’s way.

Jimmy Doolittle’s raid on Japan provoked the battle of Midway.

U.S. planes based on Midway (a miscellany of army, navy, and marine aircraft) flew to intercept the Japanese strike force. More than half the dive bombers and torpedo planes were shot down without scoring a single hit. Fifteen B-17s, soaring at twenty thousand feet, bombed the approaching flotilla but missed every ship. Meanwhile, Japanese aircraft strafed and bombed Midway’s defenses and airstrips at will, then returned to their flattops to load up for the killer blow.

Not until Nimitz’s carriers launched nearly everything they had, 151 aircraft in all, did the tide of battle turn. First to threaten the Japanese carriers were fifteen Douglas Devastator torpedo planes; slow and bulky, skimming the surface, ready to unload, when all fifteen were annihilated by zeros and antiaircraft fire. But their low-level flying pulled down Yamamoto’s fighter screen to sea level, allowing a handful of dive bombers to drop bomb after bomb on the Japanese decks. Within minutes, three Imperial carriers, carpeted with rearmed and refueled aircraft, burst into flames and foundered. The remaining Japanese carrier was mortally bombed soon after, at the price of the

Yorktown

, her belly cut open by two aircraft-launched torpedoes.

It was the first clear victory for the United States in the war. Along with losing four carriers, Japan also lost hundreds of irreplaceable pilots and never went on the offensive in the central Pacific again.

To cover up the tremendous defeat at Midway, Prime Minister Tojo Hideki hid the truth about the lost carriers from his emperor and the public, simply declaring the battle a great victory. Parades were held in Tokyo to celebrate.

5

. GUADALCANAL (AUGUST 7, 1942–FEBRUARY 9, 1943)

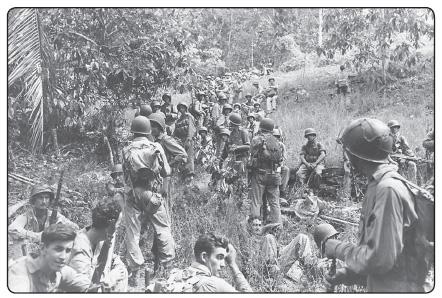

As if slowly pushing a knife into an artery, Japanese forces advanced steadily along the Solomons, a chain of islands that cut across the sea lane between Australia and North America. On the easterly island of Guadalcanal, a few thousand Japanese engineers began building an airstrip, which they believed would make the knife’s edge razor-sharp.

In reality, Guadalcanal was not capable of being a major airbase. Though nearly a hundred miles long and thirty miles wide, it was a mountainous, jungle-carpeted, malarial, scorpion-infested steam bath without enough flat land to build a decent graveyard. Still, the local headhunters called it home.

97

Adding to the misery of Guadalcanal, maps of the British-owned island were inaccurate, making navigation of jungle areas a waking nightmare.

Almost as an afterthought, some ten thousand U.S. personnel were sent to take over the airstrip. The invasion force initially met little opposition. Unwilling to hand over Japan’s southernmost possession, Adm. Yamamoto approved a naval counterattack, which abruptly sank four Allied cruisers in the area. The island quickly became a point of escalation.

98

What began as two thousand Japanese on the island became nine thousand, then twenty thousand. Major naval engagements boiled in the surrounding waters, one of which lasted a mere thirty minutes but cost the Americans six warships. Air battles flared almost daily. Not until the United States amassed fifty thousand troops on the island did fortunes move to its side.

What was supposed to last a few days dragged on for six months. There were seven major naval fights, sinking more than forty major ships (most of them American). Hundreds of planes were lost. More than seven thousand U.S. sailors, marines, and soldiers perished along with thirty thousand Japanese. Guadalcanal was the first major offensive conducted by the United States in the war, and its conclusion signaled the turn of the Solomon knife westward.

99

Four soldiers won the Medal of Honor on the beaches of Normandy. Nine marines won the Medal of Honor in the jungles of Guadalcanal.

6

. ICHI-GO (APRIL 17–DECEMBER 11, 1944)

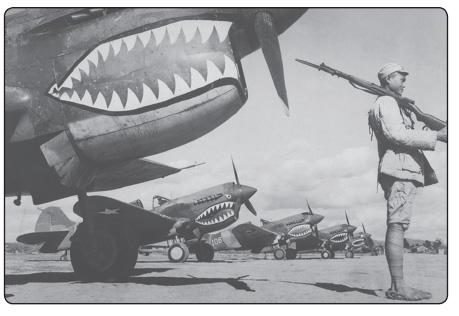

Tokyo’s intentions were ambitious, to say the least. Fifteen to thirty divisions would leave from strongpoints in east central China, head directly south for 1,000 miles, capture and destroy Chinese and American air bases along the way, and link up with Japanese forces in Indochina. The goal was to form a supply line stretching from Manchuria to Singapore. Fittingly, the name given to this bold project was Ichi-Go, “Operation One.”

The tactic was brute force—air support, artillery, and light tanks, backed by 140,000 ground troops and 70,000 horses on a front 150 miles wide. At first the offensive made considerable progress. Nationalist and regional Chinese armies often outnumbered the Japanese four to one. Yet poorly supplied and completely outgunned, the Chinese suffered casualties of twenty-to-one in several engagements. At one point, Japan pulled all available reserves from Manchuria and the mainland, creating a massive army of 360,000, its largest mobile force of the war.

100

A Chinese Nationalist protects American P-40s still sporting the shark’s teeth of the Flying Tigers. Ichi-Go’s main objectives included the destruction of these air bases in southeast China.

Though a few Chinese regional armies fought with spectacular bravery, the Chinese Nationalist Army did not. Chiang’s troops simply melted away in the face of battle. Regional commanders begged the generalissimo and his Allied chief of staff, U.S. Gen. Joseph Stilwell, for weapons, supplies, and food. Both men repeatedly denied the requests; Chiang feared arming a potential rival, and Stilwell believed the Chinese were being driven back by cowardice. Ultimately, Washington lost all discernible confidence in Chiang.

101