The History Buff's Guide to World War II (26 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

HOME FRONT

HARDSHIPS

As a basic measure of noncombatant involvement in a conflict, some comparative history may be useful. In the American Civil War no more than 7 percent of the fatalities were civilian. By the F

IRST

W

ORLD

W

AR

, the rate had climbed to 20 percent. In the Second World War, nearly 60 percent of the dead were not in the military. The phrase “fighting for our lives” had taken on a literal meaning.

Conservative estimates place civilian war deaths at more than thirty million. Of these, the Soviet Union lost at least twelve million. Many historians refuse to guess on China, where the toll was somewhere between two million and fifteen million (probably closer to the latter). Poland suffered the highest percentage, losing 15 percent of its population—nearly six million people. On average, Yugoslavia lost more civilians every two weeks than Britain lost every year.

As expected, war brought far more hardships to the home front than just loss of life. People lost limbs and eyes, their homes, sometimes their countries. Ever present among physical traumas were mental demons of anxiety, fatalism, and fear. Yet people lived on, many through astounding displays of composure and diligence. Survivors from Buchenwald to Nanking recounted how, even in the most desperate times, a pervasive fight for normalcy endured.

Listed below, and placed in no particular order, are some of the more ruthless trials set upon the home front, many of which lasted well beyond the dates of any military cease-fire.

1

. HUNGER

It was as if the four horsemen of the apocalypse had come, and famine was leading the way. First to go was prime farmland. While the Soviet Union transported many of its factories east, past the barrier of the Urals, its agricultural base naturally remained rooted where it stood, in the west and southwest. When Germany overran these areas in 1941, the Soviets lost more than one-third of their grain and grazing lands, more than half their potato acreage, and nearly the entire sugar beet region. So, too, China lost its two most cultivated regions to Japanese invasion by 1938.

1

As with most famines, the greatest harm came not from lack of food but from lack of transportation. Never in the world’s history had population centers been so large and so dependent on food shipments to sustain them.

The war sank ships, destroyed roads, killed draft animals, and commandeered trucks that transported food. For countries such as Greece, which imported a half-billion tons of grain annually, the effects were devastating. In the winter of 1941–42, Athens alone lost three hundred residents a day to starvation. Leningraders were dying at a rate of four thousand a day, with survivors reduced to killing and eating pets. In 1943 a famine in China’s Honan province sparked a civilian uprising against the Nationalist Army. By 1944 famines erupted in Holland and east India, the latter killing an estimated 1.5 million. Nearly 2 million people in Indochina succumbed to hunger the following year. Incidents of cannibalism occurred in more than one country. Women everywhere turned to prostitution to feed their families.

2

While fighting had ceased in most countries by the end of 1945, hunger had not. Russia and China were producing half the grain of prewar years. Germany experienced its worst food shortages in 1946 and 1947. Rationing continued in many countries through 1950.

3

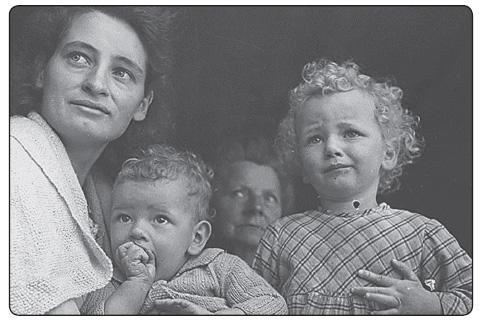

A mother masks her anguish, while her children are less guarded. As many as a fifth of all civilian casualties were less than ten years old.

In 1944, Japan’s petroleum-starved war industry took what precious food was left and literally fed it to their machines. Factory owners confiscated and processed countless tons of soybeans and coconuts for machine oil and used distilled potatoes and rice to make alcohol for engines.

2

. GROUND COMBAT

“Battlefield” had become a misnomer by the 1940s. The primary targets of conquest were not the opposing armies but the factories, ports, rail lines, ships, and towns that supplied them. If residents of such areas were unable or unwilling to leave their homes, unspeakable horrors awaited. For many the sight of bombers was not nearly as damning as approaching enemy tanks and infantry.

In addition to the shelling and shooting, there were the added chances of arson, looting, murder, and molestation. The desecration of women occurred with chilling regularity, especially in ethnically charged battles. Nations such as Burma, the Low Countries, France, Manchuria, the Philippines, Poland, Romania, and the Ukraine had the added curse of being fought over several times.

On local levels, men and machines razed villages, towns, and cities across Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Pacific. By 1944 eight out of ten buildings in Warsaw were leveled or unusable. Yugoslavia, exposed to both international and civil war, possessed a stretch of road more than one hundred miles long where not a roadside building remained standing. By 1945, the city of Manila was barely recognizable. After the war the Soviet Union designated Kiev, Leningrad, Minsk, Stalingrad, and others as “Hero Cities,” essentially for undergoing 40 percent or higher casualties. Bonn became the West German capital by default because it was one of the few major German cities with more than 40 percent of its buildings intact.

In April 1945, Kronach, Germany, begins to experience the same kind of devastation that plagued hundreds of thousands of other villages across the globe.

Upon visiting the capital of conquered Germany, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower muttered, “It is quite likely, in my opinion, that there will never be any attempt to rebuild Berlin.”

3

. IMPRISONMENT

Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 forced 110,000 Japanese Americans into relocation camps, though most of Hawaii’s 30,000 Japanese residents were not interned. The idea of interning German-born residents was briefly entertained, until it was calculated there were 600,000 of them.

4

The thought of handling such numbers did not detract two governments across the Atlantic. The Third Reich detained as few as 25,000 people at the start of the war but abruptly expanded its network of camps to hold several million at once. The Soviet Union, with a long tradition of incarcerating large numbers, also increased its rate of abductions once war began with Germany. Both states singled out ethnic groups. Doomed in the Third Reich were Gypsies, Russians, and Jewish and Catholic Poles. For the USSR the deported included Poles, Germans, Bulgarians, Chechens, Estonians, Greeks, Kurds, Latvians, Lithuanians, Tartars, and more. Rail was the transport of choice for both regimes, inexpensively carting thousands after thousands in suffocating, lice-ridden cattle cars, permitting only a fraction of the survivors to reach their assigned destinations, mostly labor installations.

5

Political prisoners were a different issue. Accused of anything from collaboration to stealing potatoes, “enemies of the state” as a whole were subject to interrogation. Methods of extraction varied with the arresting parties, but the German Gestapo depended heavily on torture and threats. Soviet interrogators steered toward depriving their subjects of food and sleep.

All told, the number incarcerated by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany may have exceeded thirty million, with as many as twenty million prisoners not surviving.

6

Of Poland’s 5.5 million war dead, most died in German and Soviet camps.

4

. AERIAL BOMBING

In his 1921 treatise

Command of the Air

, Italian Giulio Douhet predicted bombers alone would decide the outcome of future wars. By 1939 his theory had many believers, including H

ERMANN

G

ÖRING

and British air chief Marshal Arthur “Bomber” Harris. Prevalent was the conviction that precise strikes could knock out munitions factories, rail hubs, and key administration buildings, consequently shutting off life support for a mechanized army. As it turned out, bombing was hardly an exact science. A 1941 report in Britain revealed that, on average, fewer than a third of Allied bombs were landing within five miles of their desired targets. Given a factory or railhead as an objective, crews would have to drop around five thousand bombs to destroy it.

7

Mortified by this revelation, British planners decided to use the same method the Germans employed in the B

ATTLE OF

B

RITAIN

: to carpet bomb in hopes of breaking the morale of the populace and perhaps hitting a few key targets as well. The United States practiced a similar method of “area bombing” upon Japan.

Postwar studies indicated that this method also failed. Most communities hit by bombing runs became more unified, not less. But destruction came nonetheless. Though Paris and Rome were generally spared, Belgrade, Berlin, Chungking, Manila, Vienna, and many others were not. Bombed cities and towns numbered in the thousands, homes destroyed in the millions.

Most of the civilian deaths in Germany and nearly all in Japan died from bombs, or more correctly, from fires created by bombs. The highest rate of damage occurred in the last two years. France lost sixty thousand citizens in raids for the Normandy campaign. Incendiary bombing killed more than forty thousand in Hamburg and seventy thousand in Dresden.

More than half of Japan’s bombing deaths occurred in cities other than Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

8

The most destructive form of civilian bombing involved incendiary devices, which torched high-density housing at thousands of degrees.

To maintain pressure on the government of Japan to capitulate, the United States resumed conventional bombing of the country the day after Nagasaki.