The History of Florida (25 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

aged them to attack the Westoes. The enslaved Indians captured during

these raids were purchased by the English and put to work on plantations

or sold to planters in the Caribbean islands.

These tactics had direct impact on Spanish Florida. Apalachicola and

Yamassee armed by English traders attacked the villages of Christian Indians

at Franciscan missions among the Guale along the Georgia coast, enslaving

captives and forcing survivors to relocate to sites farther south and closer

to St. Augustine. Attacks next focused on the Timucua and the Apalachee.

Within two decades of their arrival at the Ashley River, Carolina traders had

moved west from Charleston and drawn into their trade network the Native

Americans located north of Florida and to the west as far as today’s central

Alabama. They had also formed alliances with Native Americans that posed

a serious threat to the continuation of Spanish Florida.

This threat to La Florida overlapped with a chal enge from French ex-

plorers who were expanding from Quebec through the Great Lakes and

down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico staking territorial claims

Raids, Sieges, and International Wars · 115

for future settlements. In 1699, Pierre le Moyne, Sieur d’Ibervil e, led an

expedition from France to establish a colony on the Gulf coast at Pensacola

Bay. When he arrived, he discovered that Spaniards were already building a

fort in a belated attempt to maintain control of the Gulf and protect Span-

ish settlements at Mexico. Ibervil e instead established Fort Maurepas at

Biloxi Bay and Fort Mississippi, south of today’s New Orleans. His goal was

to control the Mississippi River delta and block access to ships from other

European nations. From the French colony of Louisiana, traders established

partnerships with Chickasaw, Choctaw, and other Native Americans in the

vicinity, and proceeded upriver to strike similar partnerships along the nu-

merous rivers feeding into the Mississippi.

With a dynamic French presence to the west at Louisiana and an aggres-

sive and an expanding English colony to the north at Carolina, the residents

of Spanish Florida were placed in a precarious position. To strengthen its

controls, Spain authorized construction of a stone fort at St. Augustine, the

Castil o de San Marcos, and to protect the Apalachee missions and their

vital agricultural resources, the Castil o de San Marcos de Apalachee was

built in 1680 on the St. Marks River, inland from Apalachee Bay (thirty miles

south of Tal ahassee in Wakul a County). In 1696, a two-story blockhouse

with artillery and a palisade was built at Mission San Luis (in present-day

proof

Tal ahassee).

A European conflict, the War of Spanish Succession (1701–14), known

in the North American colonies as Queen Anne’s War, brought devasta-

tion to Spanish Florida. Fear that the balance of power would be upset if

the thrones of France and Spain merged following the death of Charles II

of Spain and his succession by Philip V, the grandson of the king of France,

led to a major European war. France and Spain faced off against England,

Austria, the Netherlands, and Prussia. In North America, Governor James

Moore of Carolina was determined to destroy Spain’s Florida colony and

fol ow that with an attack on the French in Louisiana. The first blow was

struck in May 1702 by Creek warriors who burned Mission Santa Fe on

the road from St. Augustine to Apalachee, and carried off Timucuan cap-

tives as slaves. In the failed Spanish counterattack that followed, the Creek

killed or captured more than 400 Timucuan and Apalachee auxiliaries of

the Spanish.

In November 1702, Governor Moore led a force of 1,200 men, primarily

Creek warriors, against the Spanish at St. Augustine. Detachments under

Colonel Robert Daniel debarked first at Amelia Island and destroyed the

116 · Daniel L. Schafer

proof

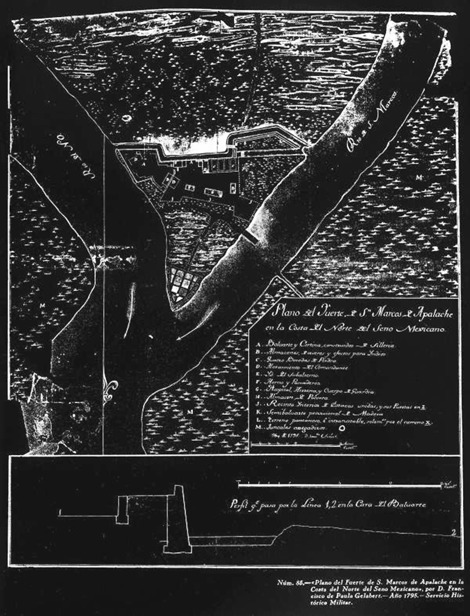

Castillo de San Marcos de Apalachee. The site of this fortification was inland from

Apalachee Bay on the St. Marks River. The site can be visited at San Marcos State Park,

off State Road 363 in Wakulla County, Florida, 30 miles south of Tallahassee. Courtesy

of the National Archives, Kew, England.

missions and vil ages there. San Juan del Puerto at Fort George Island and

Piritiriba, located south of the St. Johns on the west bank of the San Pablo,

were destroyed next.

Governor Moore had proceeded by water to St. Augustine Inlet to block

entrance to the harbor and join with Colonel Daniel’s men, who arrived on

November 10 and established headquarters at the south of town near the

convent on St. Francis Street. Spanish Governor Joseph de Zúñiga y Zerda

had already moved 1,500 town residents, soldiers, refugees, and stores of

proof

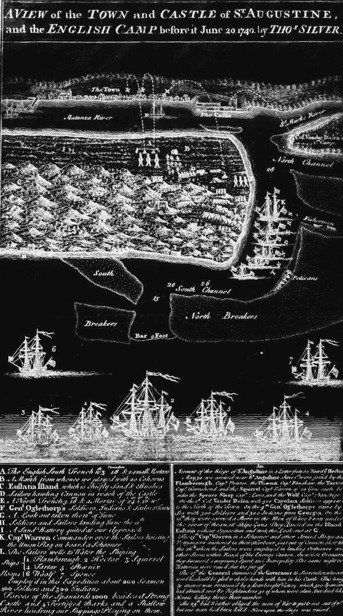

A View of the Town and Castle of St. Augustine, and the English Camp

before it, June 20, 1740. General Oglethorpe and the British invaders

from Georgia were unable to breach the walls of the Castillo de San

Marcos and called off the siege of the Spanish town. By Thomas Silver.

Courtesy of the University of Florida Digital Collections, http://ufdc.ufl.

edu/UF90000078/00001.

118 · Daniel L. Schafer

corn inside the Castillo. He also arranged for soldiers to round up a herd of

160 cattle and drive the thundering beasts through the streets of the town.

Startled English troops ran for cover as the cattle ran across the drawbridge

over the moat. Behind the protective stone wal s of the Castillo de San Mar-

cos, the Spaniards waited anxiously, praying for the arrival of a relief force

from Havana.

Unable to breach the wal s of Castillo de San Marcos, Moore laid down a

siege expecting to starve the inhabitants into submission. The Spanish relief

force that arrived from Cuba on December 26 trapped the Carolina ships in

the harbor and forced Moore to end the siege. His men torched their vessels

and ignited a conflagration in the town that destroyed religious and govern-

mental structures and left only twenty houses standing, along with Nuestra

Señora de la Soledad, built in 1572, and the hospital attached in 1597, the

first hospital in continental United States. The English invaders marched

northward, leaving more charred ruins in their path. At the entrance to the

St. Johns they boarded English ships and returned to Charleston in disgrace.

In November 1703, former governor James Moore was offered a chance

to redeem his reputation by leading fifty Carolina settlers and 1,000 Lower

Creek and Yamassee in an invasion of Apalachee province. A census of thir-

teen Apalachee missions compiled in 1689 by the bishop of Cuba, Diego

proof

Ebelino de Compostela, listed nearly 10,000 residents. Between January and

August 1704, the Apalachee, the Spanish friars and soldiers, and floridano

ranchers and farmers were swept away in attacks by Moore’s Carolina mi-

litia and al ied Creek and Yamassee warriors. Between January and April

1704, Moore’s army swept through Apalachee, destroying vil ages, killing or

enslaving as many as 2,000 Apalachee converts to Christianity, and force-

ful y persuading between 1,300 and 2,000 Apalachee to follow his army to

Charleston to avoid death or enslavement. Only the seven mission vil ages

whose leaders paid ransoms to Moore remained after the invaders departed.

After Creek warriors raided Apalachee again in June and July, only the

vil ages at San Luis, Ivitachuco, and Chacato remained. Spanish authori-

ties in St. Augustine recognized it would be futile to resist further attacks

and abandoned the Apalachee missions. A group of 800 Apalachee from

San Luis decided to march westward to join the French at Mobile, while

many more abandoned the Spaniards and migrated north and west to merge

their families into Creek vil ages along the Apalachicola, Flint, and Chat-

tahoochee Rivers. Patrice de Hinachuba, the leader of Ivitachuco, led his

vil agers eastward to Potano and established the new settlement of Abosaya

near the La Chua cattle ranch. But the Creek raids continued, focused on

Raids, Sieges, and International Wars · 119

Yustaga, Potano, and the ranch at La Chua. The new town of Abosaya was

attacked, forcing the survivors to seek safety in smal settlements outside the

town wal s at St. Augustine.

Governor Zúñiga y Zerda ordered other mission vil ages and stockades

rebuilt in the aftermath of the Carolina raids of 1702 and 1704, including at

San Francisco Potano and at the La Chua cattle ranch. As a result of hostile

Indian raids, all the new vil ages were destroyed or abandoned soon after

they were completed. In

A

History

of

the

Timucua

Indians

and

Missions

, John Hann describes an anonymous and undated map of Piritiriba dated

circa 1704 that indicates a “four-bastioned fort” with “barracks, living quar-

ters, and warehouses for supplies” was constructed—possibly as early as

1703—to protect two adjoining vil ages of refugee Guale and Mocama. Ap-

parently, San Juan del Puerto was not rebuilt. Each vil age at Piritiriba had

its own church, but prayers did not protect them from attacks that resulted

in the death and capture of 500 Indians.

Governor Córcoles y Martínez estimated that, between 1702 and 1708,

more than 10,000 Native Americans perished, yet the Creek and Yamassee

attacks continued. Even the Indian vil ages outside the wal s of St. Augustine

were attacked. Without supplies of corn and beef formerly supplied by the

Guale, Timucua, and Apalachee, St. Augustine residents were dependent on

proof

imports by water. Severe shortages and hungry times lay ahead.

In 1715, it was the Carolina colonists who were attacked by Native Ameri-

cans, this time by a confederation led by Yamassee warriors angered by Eng-

lish encroachment. More than 400 settlers were kil ed before the English

regained control, which prompted several hundred Yamassee to take refuge

with the Spanish at St. Augustine. Others who participated in the rebel-

lion migrated to Creek vil ages along the Apalachicola and Chattahoochee

Rivers.

It was to these vil ages that Lt. Diego Peña and a detachment of Span-

ish soldiers traveled in 1717 to promote trade opportunities and to encour-

age the residents to migrate to the abandoned fields formerly tilled by the

Apalachee. In support of Lt. Peña’s initiatives, the fort at St. Marks was re-

built to facilitate trade with St. Augustine and Havana. Eventual y, Creek

migrants began moving into the rolling hil s region near today’s Tal ahas-

see, but the more aggressive diplomatic and trade initiatives by the English

minimized Spanish gains.

Between 1723 and 1728, the English waged persistent war on the Yamas-

see, relentlessly destroying their vil ages along the Apalachicola and Chatta-

hoochee Rivers, as wel as in Apalachee and near St. Augustine. An epidemic

120 · Daniel L. Schafer

at St. Augustine in 1727 claimed the lives of approximately 500 Yamassee,

and more lives were lost due to a raid on Mission Nombre de Dios led by

Colonel John Palmer of Charleston in March 1728.

The next major threat to the continuation of Spanish Florida came in 1732

with the establishment of the English colony of Georgia in the disputed ter-