The History of Florida (30 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

Pensacola, 1686–1763 · 139

In 1743, a Frenchman, Dominic Serres, serving as a seaman on a Spanish merchant

ship, made a drawing of the presidio on Santa Rosa Island, the only illustration of the

presidio that exists. The view is from the interior of the bay looking south. Notable

among the buildings shown is an octagonal-shaped church, the first such building in

Pensacola’s history. Serres later became famous as a seascape painter for King George

III of England.

manned by 200 soldiers, although it would be some time before that many

proof

were in place.

A new commandant, Colonel Miguel Román de Castil a y Lugo, reached

Pensacola in early 1757. En route from Veracruz, he had been shipwrecked

on Massacre (Dauphin) Island and had lost most of the supplies and some

of the troops he was bringing to Pensacola. The soldiers who survived in-

creased the garrison to about 150 men. By August 1757, that number had

grown to 180. Stil , the new location was in no condition to defend itself

in the event of Indian hostilities, which were expected any day. Román de

Castil a quickly set about building a new stockade and establishing other

defensive measures for the presidio.

The wal s of the new stockade, built of vertical pointed stakes, were soon

completed except for the one facing the water. The wal s eventual y mea-

sured 365 by 700 feet. Within the stockade were the government house, a

church, warehouses, barracks, bake ovens, and a brick house for the gover-

nor. Outside the stockade, seven or eight paces distant, was a single line of

dwellings for the civilians, officers, and married soldiers.

Except for periodic scares, Pensacola escaped attacks by hostile Indians

for several years after Román de Castil a arrived, despite the fact that the

French and Indian War swept the hinterland. During that time the number

140 · William S. Coker

of soldiers increased to 224, including two infantry companies and one of

light artillery. Even supplies and provisions arrived more frequently. By the

summer of 1760, however, conditions began to deteriorate.

In June, fear of an attack by unfriendly Indians prompted the governor to

clear the area around the stockade, destroying the houses and moving the

occupants into the fort. If the Indian menace was not enough, in August a

hurricane destroyed half of the stockade and blew the roofs off the houses.

The Spaniards were unable to secure new cypress bark, so Pensacola’s houses

went through the winter of 1760–61 without roofs.

The year 1761 was more trying. In February, the Alibama Indians attacked

the Spanish Indian vil age of Punta Rasa on Garçon Point, kil ing several

soldiers and resident Indians. Such attacks continued periodical y, and the

situation became so alarming that, in May, Román de Castil a moved the

friendly Yamasee-Apalachino Indians from the vil ages on Garçon Point

into the stockade. In June, the captain-general of Cuba dispatched two in-

fantry companies of

pardos

(mulattoes) commanded by Captain Vizente

Manuel de Zéspedes to Pensacola. In turn, some of the women from Pen-

sacola went to Havana, but about 200 women and children remained. For

the most part, the residents were confined to the stockade, although caval-

rymen did escort them to the nearby creek for water.

proof

Again, the French came to the rescue. In September, the governor of

Louisiana, Chevalier de Kerlerec, sent a representative, M. Baudin, to help

establish peace between the Indians and the Spaniards. Baudin succeeded,

and the peace accord was signed on 14 September 1761. The Indians agreed

to cease their attacks, and arrangements were made for an exchange of

prisoners.

The question of why the French were usual y successful in such negotia-

tions has a simple answer: They carried on an extensive trade with the In-

dians, while the Spaniards did not. The French traded guns and provisions

for deerskins and other furs, and if they stopped this exchange, the Indians,

heavily dependent upon such trade, would suffer. Thus the French exercised

great influence among the natives of the area. But for Spanish Governor

Román de Castil a, the French solution of the Indian problem came too late.

By the summer of 1761, officials in New Spain replaced the Pensacola

governor with an officer who was an experienced Indian fighter, Colonel

Diego Ortiz Parril a. Although opposed to his new assignment, he assumed

command on 21 October. The new governor was appal ed at the terrible

condition of the presidio. He accused Román de Castil a and some of the

other officers of gross mismanagement. He also believed Román de Castil a

Pensacola, 1686–1763 · 141

to be involved in illicit trade, which seemed to be confirmed when a British

ship belonging to William Walton & Co. arrived later that year. In addition,

Román de Castil a and some of the officers owned and operated stores in the

stockade which charged exorbitant prices for the goods sold. But the official

residencia, the investigation into the former governor’s conduct in office,

was still not complete by May 1762, when Román de Castil a left Pensacola.

For his part, Ortiz Parril a spent the next year and more rebuilding the

presidio and preparing its defenses in the event that the French and Indian

War should again reach Pensacola. Spain final y entered the war in 1762 as

an al y of France. As a result, France ceded Louisiana west of the Mississippi

River including the Isle of Orleans, to Spain. But Spain quickly lost Havana

to the British. When the war ended in February 1763, Spain exchanged La

Florida for Havana. Thus Pensacola became a British possession.

In June 1763, a British entrepreneur, James Noble, arrived at Pensacola.

He quickly purchased a number of town lots from the departing Spaniards.

He also bought all of the lands claimed by the Yamasee-Apalachinos, prob-

ably a mil ion or more acres, for $100,000. Later, this purchase from the

Indians was disallowed for a lack of proof of his claim.

Final y, on 6 August 1763, British Lieutenant Colonel Augustin Prevost

and accompanying troops reached Pensacola. He official y accepted its

proof

transfer to Great Britain from Spanish Colonel Ortiz Parril a. Al of the

Spaniards, with one exception, and all of the Yamasee-Apalachinos left for

Havana and Veracruz in early September. The British were happy with the

strategic location that they had acquired on the Gulf coast, but they were

sorely disappointed with its ruinous condition.

What had it cost the Spaniards to maintain Pensacola’s presidios from

1698 to 1763? Over 4.5 million pesos:

Presidio Santa Maria de Galve (1698–1719)

971,763 pesos

War of the Quadruple Alliance (1719–22)

1,070,284 pesos

Presidio Isla de Santa Rosa (1722–52)

572,505 pesos

Presidio San Miguel de Panzacola (1753–63)

435,826 pesos

Other expenses charged the presidios

1,515,442 pesos

Total

4,565,820

pesos

Excluding expenses for the war of 1719–22, the cost was divided into

salaries, 45.9 percent; provisions, 38.9 percent; fortifications, 4.7 percent;

materiél, 9.5 percent; other, 1.0 percent.

Spain had accomplished only half of its original objective in occupying

Pensacola. With the assistance of the French, it had prevented the British

142 · William S. Coker

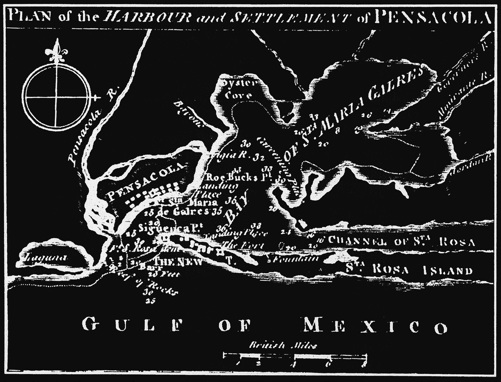

This British plan of the harbor and settlement of Pensacola was made in the year 1763,

when Great Britain assumed rule over Florida. It contains a number of inaccuracies.

proof

from establishing a base on the Gulf of México for sixty-five years. But it

had not accomplished its other major purpose, the ouster of France from

Louisiana. The British victories accomplished that ouster, but they also cost

Spain Pensacola and all of La Florida.

Bibliography

Coker, Wil iam S. “The Financial History of Pensacola’s Spanish Presidios, 1698–1763.”

Pensacola

Historical

Society

Quarterly

9, no. 4 (Spring 1979):1–20.

———. “The Vil age on the Red Cliffs.”

Pensacola

History

Il ustrated

1, no. 2 (1984):22–26.

———. “West Florida (The Spanish Presidios of Pensacola), 1686–1763.” In

A

Guide

to

the

History

of

Florida,

edited by Paul S. George, pp. 49–56. New York: Greenwood Press,

1989.

Coker, William S., et al. “Pedro de Rivera’s Report on the Presidio of Punta de Sigüenza,

Alias Panzacola, 1744.”

Pensacola

Historical

Society

Quarterly

8, no. 4 (Winter 1975; rev.

ed. 1980):1–22.

Cox, Daniel.

A

Description

of

the

English

Province

of

CAROLANA,

by

the

Spaniards

cal ’d

FLORIDA,

And

by

the

French

La

LOUISIANE.

Introduction by Wil iam S. Coker.

Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1976.

Pensacola, 1686–1763 · 143

Dunn, William Edward.

Spanish

and

French

Rivalry

in

the

Gulf

Region

of

the

United

States,

1678–1702:

The

Beginnings

of

Texas

and

Pensacola.

Austin: University of Texas Bulletin, no. 1705, 1917.

Dunn transcripts, 1700–1703. “Autos Made upon the Measures taken for the Occupation

and Fortification of Santa María de Galve.” University of Texas, Austin.

Faye, Stanley. “The Spanish and British Fortifications of Pensacola, 16981821.”

Pensacola

Historical

Society

Quarterly

6, no. 4 (April 1972):151–292. Reprinted from

Florida

Historical

Quarterly.

Folmer, Henry.

Franco-Spanish

Rivalry

in

North

America.

Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1953.

Ford, Lawrence C.

The

Triangular

Struggle

for

Spanish

Pensacola,

1689–1739.

The Catholic University of America Studies in Hispanic-American History, vol. 2. Washington, 1939.

Griffen, William B. “Spanish Pensacola, 1700–1763.”

Florida

Historical

Quarterly

27, nos.

3, 4 (January–April 1959):242–62.

Griffith, Wendell Lamar. “The Royal Spanish Presidio of San Miguel de Panzacola, 1753–

1763.” Master’s thesis, University of West Florida, 1988.

Hann, John H. “Florida’s Terra Incognita: West Florida’s Natives in the Sixteenth and Sev-

enteenth Century.”

Florida

Anthropologist

41, no. 1 (March 1988):61–107.

Holmes, Jack D. L. “Dauphin Island in the Franco-Spanish War, 1719–1722.” In

French-

men

and

French

Ways

in

the

Mississippi

Val ey,

edited by John Francis McDermott, pp.

103–25. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1969.

Jackson, Jack, Robert S. Weddle, and Winston Deville.

Mapping

Texas

and

the

Gulf

Coast:

The

Contributions

of

Saint-Denis,

Oliván,

and

Le

Maire.

College Station: Texas A&M

University Press, 1990. proof

Leónard, Irving A. “Don Andrés de Arriola and the Occupation of Pensacola Bay.” In

New

Spain

and

the

Anglo-American

West:

Historical

Contributions

Presented

to

Herbert

Eugene

Bolton,

edited by George P. Hammond, pp. 81–106. Lancaster, Pa.: Lancaster

Press, 1932.

———, ed. and trans. “The Spanish Re-Exploration of the Gulf Coast in 1686.”

Mississippi

Val ey

Historical

Review

22, no. 1 (June 1935):547–57.

Manucy, Albert. “The Founding of Pensacola—Reasons and Reality.”

Florida

Historical

Quarterly

37, nos. 3, 4 (January–April 1959):223–41.