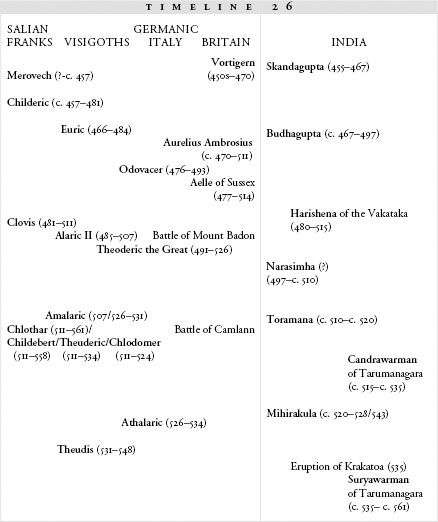

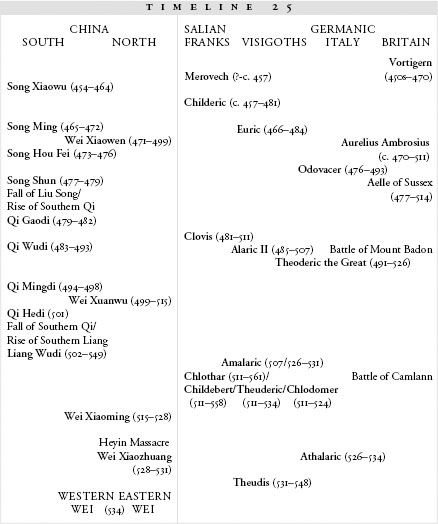

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (24 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

For the Romans (as for the Persians), kingship was quite different. In the Roman mind, the king represented something immortal and immutable that went on eternally, outlasting any king who might hold it: the idea of the Roman state. A king could pass the right to represent this idea on to his son (thus the possibility of hereditary kingship); his death did nothing to abridge it.

But in Britain, when the king died, his kingdom died with him. The next man to hold the crown re-created it anew. It was a point of view shared by most Germanic peoples, which was why Theoderic the Great had connected the possession of Roman citizenship to loyalty to his own person. Once he had conquered Italy, he

was

the kingdom of Rome.

It is impossible to know whether the old Roman idea of the state had any grasp on the mind of Ambrosius Aurelianus, that British “gentleman” of undetermined Roman lineage who may or may not have had a Roman emperor in his family tree. But Geoffrey of Monmouth, looking back from a much different Britain six hundred years later, reproduces (perhaps without meaning to) a moment when the death of a king did indeed mean the death of his kingdom. Arthur is mortally wounded on the battlefield of Camlann, but he does not die; he hands his crown to his cousin and is taken away to the Isle of Avalon to be healed. His kingdom survives because

he

survives, even though he is far away and mysteriously divided from his people. Arthur

becomes

the idea of the British state, in a time when the state and the king were the same. Like the idea of the state itself, he exists eternally.

I

N

511,

THE SAME YEAR

as the battle at Camlann, King Clovis of the Franks died.

He had ruled as sole king of the Frankish state for only two years and did not name an heir to his crown. Instead, he left his kingdom to the joint rule of his four sons: Childebert, Chlodomer, Chlothar, and Theuderic (not to be confused with Theoderic the Great of Italy; the name, along with its variations, was the Germanic equivalent of the English “Henry”). Clovis had fought to earn his title “King of the All the Franks,” and his realm was filled with warlike Franks who still carried with them the old Germanic ideal of kingship: that they had the right to choose their king. They would have bitterly resented any attempt to leave the realm to a single designated heir, one who had not proved himself in battle. Instead, Clovis had left rule of the Franks to his

clan

, which was quite different—and a much more familiar idea to the Franks, who

were

accustomed to recognizing the leadership of the Salian clan over the others.

Each of the four sons chose a different city as the center of his power. The oldest son, Theuderic, went to Reims; Chlodomer claimed Orleans; Childebert stayed in Paris; and the youngest son, Chlothar, took Soissons as his capital. In 524, the first crack appeared in the arrangement. When Chlodomer was killed on an expedition against the Burgundians, his younger brother Chlothar led the other two siblings into Orleans to kill the dead brother’s sons before they could lay claim to their father’s portion of the crown. The four kings had become three.

The old Germanic clan system was inclined to plunge kingdoms into civil war—but it kept incompetent kings out of the throne room. In 531, the young Visigothic king Amalaric, who had come into his majority but had failed to prove himself an effective warleader, was murdered by his own men. They elected a new king in his place: an officer named Theudis who was not of royal blood. Nor was he even a Visigoth. He was from Italy, an Ostrogothic soldier-official who had been sent to Hispania some years before by Theoderic the Great of Italy in order to watch over the court while Amalaric was a child.

But his blood mattered less than his strength, and he became the new king of the Visigoths. From this point on, ancestry played little part in the selection of Visigothic kings; the nation had reverted to the old Germanic method of choosing their ruler.

16

Between 497 and 535, the Hephthalites build a kingdom in north India, and Krakatoa’s eruption troubles the world

B

UDHAGUPTA, EMPEROR OF

the Gupta domain, died in 497 after a thirty-year reign. It is unclear exactly who followed him on the throne, but most likely his brother Narasimha took control of the empire, which had shrunk drastically from its height under their great-great-great-uncle Chandragupta II. Tributaries had wandered away, minor kings had asserted their independence, and the Hephthalite trickle down into the north of India had turned into a flood.

One Hephthalite warrior emerges from the faceless horde: Toramana, a warleader who conquered his way into northern India between 500 and 510, subduing one petty king after another. By 510, he had pushed his way through the empire all the way to the city of Eran, on the southern edge of the Gupta domain.

The governor of this area, Bhanugupta, was himself of royal blood. Together, he and his general, Goparaja, mounted a great defense against the Hephthalites. It proved fruitless; Goparaja was killed in the fighting, while Bhanugupta simply disappeared from the historical record. Narasimha’s fate is unknown; Toramana claimed Eran for his own, and Gupta power was forced all the way back into its eastern cradle, while Toramana declared himself king.

1

Toramana’s original domain lay west of the Indus, in land he kept hold of as he pushed south across the mountains. This gave him an empire that stretched from the eastern borders of Persia down across the mountains into India, breaching the physical border between Central Asia and India. He established his capital city at Sakala, and in a brief time Sakala grew into a metropolis, a “great centre of trade.”

The Questions of King Milinda

says that Sakala abounded

in parks and gardens and groves and lakes and tanks, a paradise of rivers and mountains and woods. Wise architects have laid it out, and its people know of no oppression, since all their enemies and adversaries have been put down. Brave is its defence, with many and various strong towers and ramparts, with superb gates and entrance archways; and with the royal citadel in its midst, white walled and deeply moated. Well laid out are its streets, squares, cross roads, and market places…. So full is the city of money, and of gold and silver ware, of copper and stone ware, that it is a very mine of dazzling treasures. And there is laid up there much store of property and corn and things of value in warehouses—foods and drinks of every sort, syrups and sweetmeats of every kind.

2

In wealth and glory, the account concludes, Toramana’s city was like the city of the gods.

Nevertheless his empire still had some of the qualities of a nomad’s kingdom. In the words of historian Charles Eliot, the Hephthalites “overran vast tracts within which they took tribute without establishing any definite constitution or frontiers.”

3

Like the Guptas, the Hephthalites did not attempt to enforce laws or tight administrative structures across their domains. A Chinese ambassador who visited Toramana’s court remarked that “forty countries” paid tribute to the Hephthalite king, but the payment of goods and money was the only sort of dominion that the empire exerted over the peoples on its edge.

Toramana, building up his great capital city, seemed content with this. But when he died sometime between 515 and 520 and was succeeded by his son, crown prince Mihirakula, the nature of the empire changed.

Mihirakula was a throwback to his nomadic roots: uncouth, rough-edged, and particularly hostile to the Buddhist faith of his new subjects. The Hephthalites had been converted, some decades earlier, to the Manichean and Nestorian Christianity that had filtered eastward through Persia towards them. Perhaps because of the fluidity of his borders, Mihirakula decided to enforce a new kind of orthodoxy: to get rid of Buddhism.

*

He did not seem to view Hinduism with the same suspicion. In fact, the Indian historian Kalhana, writing six centuries later, says that Mihirakula’s hostility enabled the Hindu brahmans to gain power in his empire: they accepted grants of land from him, making themselves more powerful than their Buddhist countrymen. But he saw Buddhism as the enemy of his power, most likely because it was the religion of the Guptas.

4

The emperor Budhagupta, whose name gives tribute to the Buddha himself, had been followed by equally devout Buddhist emperors: first by his brother Narasimha and then by Narasimha’s son and grandson, each ruling over progressively smaller bits of empire. By the time Mihirakula inherited his father’s throne, the Gupta dominion had shrunk to the area of Magadha, in the Ganges valley. Nevertheless, the Guptas remained the most powerful opponent on the Indian frontier, and Mihirakula set out to destroy their religion.

5

Sometime around 518, a Buddhist mission came to the north of India from China, searching for Buddhist scriptures to collect and preserve. According to their own records, they managed to leave India with 170 volumes. They also met Mihirakula and were unimpressed with him. “The disposition of this king was cruel and vindictive,” their account tells us, “and he practised the most barbarous atrocities.” Although the Indians he ruled were primarily Hindu (“of the Brahman caste”), they had prized Buddhist teachings—until Mihirakula came to power and began to destroy Buddhist temples, monasteries, and books.

6

Rather than strengthening his kingdom, Mihirakula weakened it. The Guptas, still trying to drive the Hephthalites out, were joined by local rulers who resented Mihirakula’s high-handed rule. In 528, the governor of Malwa—a province that had first belonged to the Guptas and then had earned independence before falling under the control of the Hephthalite king—won a great battle against Mihirakula so decisively that he was able to drive the enemy back up into the northern reaches of the Punjab. Mihirakula lived for another fifteen years in his diminished kingdom, but he was never able to return to the northern Indian lands he had once ruled.

The Guptas were not able to fill the power void. Monasteries and cities had been destroyed in the Hephthalite wars; trade routes had been disrupted. Over the next years, northern India returned to its patchwork condition, filled with little states ruled by independent kings, tribes who migrated from central Asia into the lands with no king, and small communities formed by farmers and shepherds who came down over the mountains and settled in the plains. These small kingdoms and tribes joined together, when necessary, to drive off any Hephthalite attempts to return, but no strong ruler emerged from these sporadic efforts at defense.

7

In central and south India, a patchwork of kings continued to rule. We know little of them except what we can glean from inscriptions and coins: names and dates of rule. The Indian kingdoms did not aspire to the universal dominion visualized by the kings of the west. Nor did their scholars attempt to write narratives that would tie events together into some sort of huge and meaningful pattern. Scholarship was far from absent: despite the chaos farther north, the astronomer Aryabhata, who had his home in the Gupta domain, had by 499 calculated the value of pi and the exact length of the solar year, and suggested that perhaps the earth was a sphere that moved around the sun while rotating on its axis. This was most certainly an assertion about a universal pattern, but it was an observation, not an attempt to impose meaning on a scattered variety of political events.

T

HE

I

NDIAN KINGDOMS

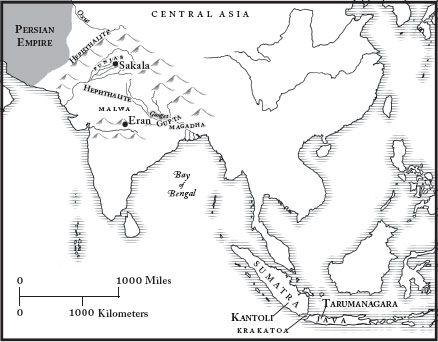

on the southeastern coast traded across the Indian Ocean with the islands farther east: the large island of Sumatra, and the smaller island of Java. We do not know a great deal about these kingdoms, apart from their ongoing trade with India. On the southern end of Sumatra, a kingdom called Kantoli was in its very early stages (it would develop further in the next century), while on the northern end of Java, the kingdom of Tarumanagara was ruled by King Candrawarman. Between the two islands lay the mountain of Krakatoa: a volcano, slowly building up a head of steam and lava beneath its ice-capped surface. In 535, Krakatoa erupted.

*

The explosion hurled pieces of the mountain through the air to land as far as seven miles away. Tons of ash and vaporized salt water exploded upwards into the air, forming a plume perhaps thirty miles high. The land around the volcano collapsed inward, forming a cauldron of rushing seawater thirty miles across. The Indonesian chronicle

The Book of Ancient Kings

describes a tidal wave sweeping across Sumatra and Java, which at the time may have been a single island: “The inhabitants were drowned and swept away with all their property,” it reads, “and after the water subsided, the mountain and the surrounding land became sea and the island [had been] divided into two parts.”

8

The Book of Ancient Kings

is not entirely reliable, since this account comes from a much later transcription and may reflect more recent eruptions. But the Indonesian records are not the only ones that testify to a 535 disaster. The effects of Krakatoa’s eruption rippled across a much wider landscape. In China, where the sound of the explosion was recorded in the

History of the Southern Dynasties

, “yellow dust rained down like snow.” Procopius reports that in 536, all the way over in the Byzantine domain, “the sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon, during this whole year, and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear.” Michael the Syrian writes, “The sun was dark and its darkness lasted for eighteen months; each day it shone for about four hours, and still this light was only a feeble shadow…. [T]he fruits did not ripen and the wine tasted like sour grapes.” The ash from the explosion was spreading across the sky, blocking the sun’s heat. In Antarctica and Greenland, acid snow began to fall, and continued to blanket the ice for four years.

9

26.1: India and Its Southeast Trading Partners

Two years later, in the early fall of 538, the Roman senator Cassiodorus, serving at the Ostrogoth court in Ravenna, lamented in a letter to one of his officials,

The Sun, first of stars, seems to have lost his wonted light, and appears of a bluish colour. We marvel to see no shadows of our bodies at noon, to feel the mighty vigour of his heat wasted into feebleness, and the phenomena which accompany a transitory eclipse prolonged through a whole year. The Moon too, even when her orb is full, is empty of her natural splendor. Strange has been the course of the year thus far. We have had a winter without storms, a spring without mildness, and a summer without heat. Whence can we look for harvest, since the months which should have been maturing the corn have been chilled?…The seasons seem to be all jumbled up together, and the fruits, which were wont to be formed by gentle showers, cannot be looked for from the parched earth…. [T]he apples harden when they should grow ripe, souring the old age of the grape-cluster.

10

Crop failure was not limited to the east. Tree-ring data from as far away as modern Chile, California, and Siberia show a “drastic drop in summer growth” from around 535 until about 540: this testifies to cold, dark summers. The darkening of the sun was producing plague, hunger, and famine across the medieval world.

11

And to the east, the civilizations on the islands of Sumatra and Java were destroyed. In Tarumanagara, King Candrawarman was killed; his heir, Suryawarman, moved the capital of his kingdom farther east, away from the site of the catastrophe. But the kingdom had been dealt a death-blow. The once-thriving culture on the island was reduced to shambles; all that is left now are a few inscriptions and the foundations of destroyed temples to the gods of Hinduism and to the Buddha.

12