The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (68 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

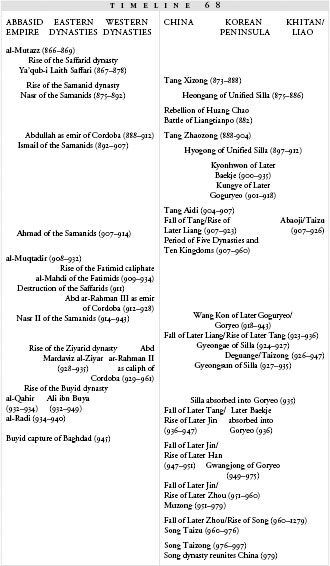

68.1: Song, Liao, and Goryeo

Reunifying the south turned out to be a lifelong task. In the sixteen years of his reign, Song Taizu defeated three of the six southern states. Halfway through his time on the throne, he made a run at attacking the Northern Han; but he was forced to retreat and afterwards resigned himself to the Northern Han’s existence.

Struck down by illness on campaign, Song Taizu died in 976. His younger brother, Song Taizong, took the throne. Within two years he had finished the conquest of the south and was ready to bring the Northern Han—the last remaining state—to heel. In 979, Song Taizong personally led his army against the Northern Han capital, the city of Taiyuan. A long savage siege followed. At last Song Taizong, showing the same canny political sense that had characterized his older brother, offered the Northern Han ruler a golden handshake: if he would step down and hand his kingdom over, Song Taizong would reward him with safety, an estate, and a lifetime of ease.

14

Finally, the Northern Han was in Song hands. With the surrender, the Song had spread itself once again over the Chinese mainland. The fractured landscape of the east had drawn itself together: the Song, the Liao, and Goryeo now governed the once divided lands.

Between 924 and 1002, England and Norway are both united under single kings, Norse colonists settle in Greenland, and Sweyn Forkbeard adds England to his North Atlantic empire

I

N

924, E

DWARD THE

E

LDER

—king of southern England, son and heir of Alfred the Great—capped a quarter century of fighting with his finest achievement yet: he forced the west and the north to submit to him. “All the race of the Welsh sought him as their lord,” the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

tells us, “…the king of Scots and all the nation of Scots chose him as father and lord. [So also did]…all those who live in Northumbria, both English and Danish and Norwegians and others.”

1

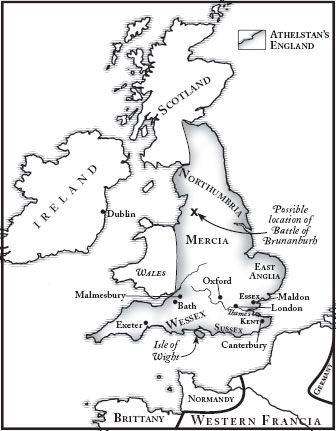

Edward was not king of a united island. The far edges of Northumbria remained independent from him, and the submission of the Welsh and the Scots appears to have been a simple matter of tribute payment. But he could claim with justice to be the first king of all the Anglo-Saxons. He had inherited the kingdom of Wessex from his father Alfred and after the death of his sister had taken control of Mercia as well. With the exception of the Danish kingdom which remained in the far north, the country that we now think of as England was his.

2

He had decreed, in a reversion to Germanic custom, that his realm be divided between his two elder sons. But one of these sons died “a few days after his father” (William of Malmesbury, who records the death, gives no details) and the other, Athelstan, became sole king.

3

Like his father and grandfather, Athelstan spent his life in war. He fought rivals for the throne; he fought rebel Anglo-Saxon noblemen who disliked the idea of a single Anglo-Saxon king; he had to reconquer the Welsh and the Scots, who tried to slip from his control. And he mounted a stealth takeover of the Viking holdouts in the northern reaches of the Danelaw. “The most vigorous and glorious Athelstan, king of the English, gave his sister in marriage with great ceremony to King Sihtric of the Northumbrians,” John of Worcester tells us. Sihtric, ruler of that persistent Danish kingdom in the north, was already elderly. When he died the following year, Athelstan invaded in his sister’s name and claimed the holdout lands in Northumbria for his own.

4

He had brought an end to the Danelaw, and he was well on his way to wiping out the last traces of the independent Anglo-Saxon kingdoms that had once carpeted the island. The task was finally finished in 936, when Athelstan fought a pitched battle in an unknown location (probably somewhere in the northeast of England) against an alliance of Northumbrian Vikings, Anglo-Saxon noblemen—five of whom claimed the title of king over their own patches of land—and Scots, led by their long-lived king of Scotland, sixty-year-old Constantine II. There, he crushed the resistance to his overlordship: “King Athelstan and his brother, the atheling Edmund…killed five underkings, and seven earls,” writes John of Worcester, “and more blood was shed than hitherto had been shed in any war in England.”

*

Constantine II of Scotland lost his son in the fight and was forced to flee. The Battle of Brunanburh was so fierce that it earned its own poem in the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

:

Here King Athelstan, leader of warriors,

ring-giver of men, and also his brother,

the aetheling Edmund, struck life-long glory

in strife round Brunanburh…. There the ruler of

Northmen, compelled by necessity,

was put to flight, to ship’s prow,

with a small troop…. Never yet in this island

was there a greater slaughter.

5

The victory brought all of England firmly under one king for the first time. Alfred the Great had been king of Wessex; Edward the Elder, king of the Anglo-Saxons; Athelstan was now king of England and had even forced the kings of Wales and Scotland to acknowledge his power. He had lived up to his father and grandfather and moved beyond them. “Intent on not disappointing the hopes of his countrymen and falling below their expectations,” William of Malmesbury writes, “[he] brought the whole of England entirely under his rule.”

6

It had taken over three generations of fighting to pull the struggling English inside a single national border, and that border—straining under the tension—popped open again almost at once. Athelstan, king of all England, died in 939 and was succeeded by his seventeen-year-old half-brother, Edmund the Just. The Irish king Olaf I of Dublin invaded and took the midlands of England away, and Edmund was not able to reconquer them until 942, after Olaf died.

69.1: Athelstan’s England

Edmund ruled his reunified country for barely four more years. In 946, he was killed in a freak encounter. He was presiding over a feast in honor of St. Augustine, founder of Christianity in England, when he noticed among the guests a thief whom Edmund, sitting in judgment (one of the king’s regular duties), had ordered exiled. The sight infuriated him. He stood up and tackled the robber, who drew out a knife and stabbed Edmund in the chest.

7

Edmund’s guard came running and hacked the criminal to pieces, but Edmund died within hours. He was twenty-four years old; he left a five-year-old son, but during the child’s minority the crown was taken by Edmund’s brother, Edred Weak-Foot. The nickname came from Edred’s generally poor state of health. Nevertheless, he held the country together, even in the face of a revolt in Northumbria: “He almost wiped them out,” William of Malmesbury says, “and laid waste the whole province with famine and bloodshed.” When he died of chronic illness in 955, he passed a unified nation on to his nephew.

8

The new king, Edwy All-Fair, was fourteen: “a wanton youth,” William tells us, “and one who misused his personal beauty in lascivious behaviour…. On the very day of his consecration as king, in a very full gathering of the nobles, while serious and immediate affairs of state were under discussion, he burst out of the meeting…and sank on a couch into the arms of his doxy.” William adds that the English bishop Dunstan, who was at the meeting, followed his king into the bedchamber, dragged him back out, and together with the archbishop of Canterbury forced him to give up his mistress and attend to his business.

9

This extraordinarily precocious behavior is probably a myth, but Edwy did soon make an enemy of both Dunstan and the archbishop. Raised without a father, he had become a puppet of court officials who hoped to gain control of the kingdom for themselves. Under their influence, he deprived the monasteries of their tax revenues, destroying the power of the abbots and monks to defy the throne. (William of Malmesbury adds, indignantly, “Even the convent of Malmesbury, where monks had dwelt for over two hundred and seventy years, he made into a bawdy-house for clerks”—which probably explains his dislike of Edwy.)

Once again, the ghosts of the old Anglo-Saxon kingdoms reared their heads. The Mercian and Northumbrian noblemen, seeing the opportunity to reassert their power against both king and church, decided to throw their weight behind Edwy’s younger, easily controlled brother Edgar. They proclaimed him as rival king to Edwy. In 957, only two years after coming to the throne, Edwy lost a battle against his brother and his brother’s supporters at Gloucester, and the two divided the kingdom: fourteen-year-old Edgar ruled north of the Thames, and Edwy, now sixteen, ruled in the south.

In 959, Edwy died at the age of nineteen, and his brother Edgar became king of all England. Edgar proved more strong-minded than his older sibling. Once on the throne, he took his own road. He restored the monasteries of England, giving the abbots and monks the power to govern their own lands: “They are to have in their court the same liberty and power that I have in my own court,” he decreed, “both in pardoning and in punishing.” This shrewd legislation at once made all of the abbots and priests in England into king’s men, and gave Edgar the backing he needed to reduce the power of his would-be masters. By 973, Edgar was in full control of his country and had extracted oaths of loyalty from the king of the Scots and the king of the Welsh.

10

He had now been on the throne of England for fourteen years but had never actually been crowned. In fact, up until this time none of the kings of England had gone through a coronation ceremony; Edgar was the fourth king to rule over the entire country, but all of Alfred’s descendents, like their great forebear, had reigned as warriors, holding their power only as long as they could hold their swords.

But Edgar, in making the church his firm ally, had earned the right to be legitimized by a greater power than the god of war. Dunstan, now archbishop of Canterbury, created a formal ceremony that would recognize the king’s sovereignty—a ceremony that is described in all of the chronicles of Edgar’s reign. “He was blessed, crowned with the utmost honour and glory, and anointed king in his thirtieth year at Pentecost, 11 May,” writes John of Worcester, highlighting the king’s age; thirty, according to the Gospels, was when Jesus emerged into the public eye as the Son of God. The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

remembers the coronation in alliterative Anglo-Saxon verse:

Here, Edgar, ruler of the English,

was consecrated as king in a great Assembly

in the ancient town…. There was great rejoicing

come to all on that blessed day,

which children of men name and call

Pentecost Day. There was gathered,

as I have heard, a pile of priests,

a massed multitude of monks.

11

With the church behind him, Edgar sat on the throne as crowned king of England, his country bound together both by battle and by ceremony.

Two years later, he was killed by a swift illness and his heirs found the crown slipping from their hands. The Northmen were coming, and this time they were under the command of a king.

T

HE EARLY HISTORY

of the peoples north of the Baltic is preserved very imperfectly in heroic sagas; what glimpses we get show a familiar, slow progression from tribal patchwork to unified kingdom.

By the middle of the ninth century, the southeastern lands were ruled by Swedish kings from the area known as Uppland; the very southern tip of the Scandinavian peninsula, the islands in the Baltic itself, and the peninsula of Jutland were under the control of kings from the peoples known as the Dani.

The peninsula’s western half, home of the Norse tribes, remained divided and chaotic for longer. Sometime around 870, the rule of the coastal lands known as Vestfold fell to a ten-year-old named Harald; Harald, first with the help of his uncle and regent, and then on his own, began a seventy-year campaign to unite the Norse under one crown.

*

“King Harald swore an oath not to cut or comb his hair, until he had become sole king of Norway,” the epic

Egil’s Saga

tells us, “and so he was called Harald Tangle-Hair.”

12

In a great sea victory around 900, the Battle of Havsfjord, Harald Tangle-Hair defeated the armies of his most dangerous enemies, the Norse princes Thorir Long-chin and Kjotvi the Wealthy. “This was the last battle King Harald fought in Norway,”

Egil’s Saga

concludes, “for he met no resistance afterwards and gained control of the whole country.”

13

It actually took Harald most of his long life to unify Norway under his rule, and even then his control over the country remained shaky and contested. The western Scandinavian lands were chaotic and blood-soaked, and the constant fighting sent more Vikings abroad looking for new homes: more to England, more to Normandy, and quite a few westward to the large island of Iceland, where they joined the small struggling colonies that had been established there in the ninth century.

14

Harald Tangle-Hair’s personal life did nothing to smooth the troubled waters; his appetite for conquest was matched by his libido, and he fathered between ten and twenty sons with a variety of wives and mistresses. When he died, probably in the early 940s, the loosely united country again fell apart into a mess of battling noblemen and princes: the noblemen vying for power over their own estates, the princes hoping to establish themselves as the next king of all Norway.

Harald’s youngest son, Hakon the Good, eventually emerged as the victor, but he had to fight hard to keep the title: his older brother Erik Bloodaxe, who was married to the sister of the Danish king Harald Bluetooth, mounted a fifteen-year campaign to take the crown away. Erik Bloodaxe himself fell in battle against his brother around 955, but his “wolf-pack” of sons, in alliance with Harald Bluetooth of Denmark, carried on with the civil war.

15