The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (22 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

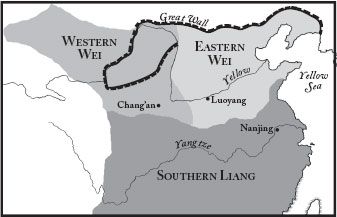

Between 479 and 534, the Liu Song collapses in the south, and the Bei Wei splits apart in the north

W

HILE THE KINGDOMS

to the north and west raided the ancient Chinese traditions for themselves, the Liu Song were falling apart. The undignified emperor Song Xiaowu, who had abandoned the principles of Confucian order in favor of pleasure and idleness, had been succeeded by Song Ming, who was nicknamed “the Pig.” After seven years, Song Ming was followed by Song Hou Fei, an undisciplined teenager who ruled only three years before his antics (painting a target on the stomach of a dozing official and then shooting blunt arrows at it) became unendurable. The court officials assassinated him and instead elevated his thirteen-year-old brother, Song Shun.

1

Two years later, in 479, an exasperated aristocrat took the throne by force and declared himself to be Qi Gaodi, first emperor of a new dynasty. The Liu Song dynasty was finished; the Southern Qi dynasty had arrived.

However, the Southern Qi dynasty turned out to be little more than a family grasping at the distant possibility of power. Qi Gaodi, elderly when he came to the throne, died within three years and passed his throne to his son, Qi Wudi. Qi Wudi kept power for ten years, but at his death a family free-for-all ensued; eventually Qi Wudi’s brother seized power as Qi Mingdi in 494. He ruled for only four years and then died (or, as a later historian put it, “was compelled to drop the sceptre which he had grasped through bloodshed and murder”).

2

His successor, his son Qi Hedi, was nicknamed “the Idiot King” for his apparent lack of sense (during his father’s funeral he fell over laughing at the sight of a bald-headed man), but he was sensible enough to tax his people heavily in order to build a beautiful new palace. The taxes were such a burden on the population that it was not uncommon to see travellers weeping over their ruined fortunes as they walked along the road.

Finally Qi Hedi went one step too far, when he poisoned an official whom he suspected of plotting against him. This official was the brother of the general Xiao Yan, who had the loyalty of the army. When Xiao Yan heard of the murder, he turned his men out in open rebellion, posting public calls for additional troops. He marched on the Southern Qi capital, Nanjing (also known as Jianking), and laid siege to it for two months. At the end of this wretched time, the people of the city—starving and famine-wracked, over eighty thousand of them dead—stormed the palace and murdered Qi Hedi. They preserved his head in wax so that they could show it to the general when he marched into the city.

3

The Southern Qi dynasty had lasted from 479 to 501, barely a single generation. Xiao Yan, now the most powerful man in the kingdom, lingered before taking power himself; for a little over a year, he called himself prime minister and put his energies behind supporting Qi Hedi’s sixteen-year-old brother in

his

claim to the throne. The southern Chinese kingdom was in the grip of an idea: it needed a hereditary ruler. Unlike Rome, China had never been a place where a general could simply take power because of his strength. He had to fit into the dynastic system, the system that lent to its members a sheen of legitimacy because they belonged to a royal family. Even if that family had just taken power, it still had to

define itself

as a royal family.

Less than a year after the death of the Idiot King, the general convinced the teenaged emperor to officially hand power over to him. We do not know what kind of pressure he exerted, but undoubtedly the young man thought that performing a ceremony that officially transferred imperial power to his prime minister would save his life. He was wrong. When the assassins arrived to kill him, they allowed him to drink himself into a stupor before strangling him; they liked him and wanted his death to be an easy one.

4

Xiao Yan took power in 502 under the royal name “Liang Wudi,” as the first king of a new dynasty. This third southern dynasty, the Southern Liang, would hold power for a little over fifty years, forty-seven of those under Liang Wudi himself.

But it would still identify itself as a

dynasty

. Liang Wudi transformed his own undistinguished family into royalty, worthy heirs of the dynastic succession of imperial China. And his strong personality did give the south a temporary anchor. He spent most of his years on the throne trying to rebuild the nation’s bureaucracy; he built five new Confucian schools for the training of young officials, declared that all heirs to the throne must be fully educated in Confucian ethics, and even instituted a system for peasants and the poor to complain anonymously about the behavior of the rich so that they would not fear reprisals. He also beat off an attack from the Bei Wei and shored up the frontier defenses.

He was a Buddhist, and in the years of his reign, his devotion to his faith grew. He sponsored the travels of monks from India so that they could come and preach in the capital city; he built temples (by the end of his reign, there were almost thirteen thousand within the Southern Liang borders); he ordered the gathering of the first Chinese Tripitaka, a comprehensive collection of Buddhist scriptures; he did his best to make sure that Buddhist prohibitions against the taking of life were followed, going so far as to order that all sacrifices demanded by Confucian or Taoist rites be carried out with vegetables and flour cakes shaped like animals standing in for the usual sacrificial victims.

5

He was doing his best to undergird his claim to the crown by displaying his virtue. As a southern ruler, he had placed himself in the ancient royal tradition that stretched back for thousands of years, and that royal tradition offered a way to legitimize his grasp for power. Virtuous emperors were Heaven-blessed, with divine approval giving them a mandate to rule. Since the very first emperors had ruled in the Yellow river valley, historians and philosophers had argued that they held power

because

of their virtue. “They were constantly attentive to ritual,” Confucius had said, explaining

why

the first emperors were given the Mandate of Heaven to rule, “exposed error, made humanity their law and humility their practice. Any who did not abide by these principles were dismissed from their positions.”

6

A dynasty could lose the right to rule—the Mandate of Heaven—if it became tyrannical and corrupt. Liang Wudi’s new dynasty would

earn

the Mandate of Heaven through displaying its virtue.

This strategy proved, in Liang Wudi’s case, to have a sting in its tail. As he developed his virtue, he became more and more convinced that Buddhism required him to renounce his ambitions to earthly power. In 527, he took off his royal robes, put on a monk’s robe, and entered a monastery, following its rules and disciplines and finding in it, according to his chroniclers, greater joy than he had ever found in his palace.

7

His ministers begged him to come out and take back his crown; his renunciation had apparently not extended to designating an heir, and they were having difficulty running the country without the authority to make royal decrees. The head of the monastery saw a good thing and refused to release the king from his vows until the ministers had paid a huge ransom out of the royal treasury. With the money handed over, he expelled Liang Wudi from the monastery, and the king went reluctantly back to rule the Liang state.

T

O THE NORTH

, Wei Xuanwu ruled the Bei Wei from the new capital at Luoyang. His invasion of the south had failed, thanks to Liang Wudi’s competent resistance, and although he launched several more attacks, he decided within five years that attacking the Southern Liang was fruitless. Instead, he concentrated on carrying on his father’s campaign to sinicize the northern kingdom into complete Chinese-ness.

But the effort to combine the two worlds of the Bei Wei—the dynamic world of the nomadic soldier and the orderly world of the settled kingdom—now began to bear bitter fruit.

In the old nomadic clan system, tribal leaders held more or less equal authority, with one leader granted slightly greater power to oversee the joint efforts of the tribes. The remnants of this system troubled Wei Xuanwu. He was surrounded by local “aristocrats,” offspring of the tribal leaders, who claimed the right to control their own portions of land, while collecting taxes from the peasants who lived on this land (taxes that were supposed to be paid over to the royal treasury) and raising armies from the population they governed (armies that were supposed to serve the interest of the royal family). These landowners existed on the thin boundary between two identities—powerful nobleman loyal to the throne and independent petty ruler—and their natural tendency was to lean towards independence.

8

In an effort to corral their power, Wei Xuanwu continued his father’s attempts at land reform. New laws decreed that the land in the Bei Wei kingdom belonged, not to individual families or noblemen, but to the government. The government had the right to assign land to individuals, who would farm it, support their families with it, and pay taxes from it directly to the throne. When a farmer died, the government could then reassign his land to someone else.

This system, called the

juntian

, or “equal-field” system, had been used by previous Chinese dynasties farther south, but never by the northern kingdoms. It kept noblemen from collecting more and more land and passing it on to their sons, something that tended to create independent hereditary kingdoms within the Bei Wei borders. But it also produced huge resentment from the ex-tribal leaders who saw their traditional power under attack.

Furthermore, it deprived those leaders of their private armies. In the old system, they had provided the throne with soldiers, whose first loyalty was to the noblemen who owned their homes and whose

second

loyalty was to the king. In this new, equal-field system, soldiers (like families) were given fields of their own, which they farmed in return for serving in the king’s army for a certain number of months per year. This broke their tie to the noblemen and reforged it directly to the king.

9

These noblemen were caught in the hard press of transition. Like the king himself, they longed to be Chinese. So even while they resented the decrease of their traditional powers, they found themselves forced to protect their new identity by distancing themselves from their rough warrior past.

In the reign of Wei Xuanwu and his successor, this “distancing” took the form of scorn for the soldiers who were posted on the northern border. The Bei Wei kingdom was under constant attack from the nomadic peoples who had

not

settled into kingdoms, who still roamed in the high grasslands farther to the north. For many years, part of the Bei Wei strategy for dealing with these nomads was to capture them and then integrate them into the garrisons posted along the northern frontier—controlling the threat, in essence, by bringing part of it within the Bei Wei borders and into the Bei Wei army.

10

This meant that the frontiers were primarily barbarian, and that the northern garrisons remained far closer to their nomadic roots than the aristocrats at court. The move of the capital city south to Luoyang had increased the distance between northern soldiers and upwardly mobile noblemen even more. Assignment to fight on the northern frontier, once an honor, became a punishment. Aristocrats were suspicious of the loyalty of the northern garrisons, always ready to see treachery and revolt in the slightest unexpected movement. In 519, one of the noblemen who served at the royal court suggested that soldiers no longer be eligible to hold government offices—a proposal that reflects the growing aristocratic scorn for a part-barbarian army. It was the same scorn that had kept the great Roman soldiers Alaric and Stilicho, halfway across the world, from rising to the throne.

11

When word of the proposal got out, the soldiers in Luoyang rioted. Wei Xuanwu had died in 515, leaving his wife the empress dowager as regent for his young son Wei Xiaoming, and the empress quelled the riot by promising that the idea would never be put into practice. But the contempt of the gesture revealed a deep hostility between the border and the court. In 523, the garrisons along the north began to revolt.

Fighting between the Bei Wei and its own border guard dragged on for several years. The empress dowager, who was supposed to be running things in Luoyang, had earned herself the nickname “Inattentive Empress” for her habit of ignoring anything that was happening outside the city, and the northern rebellions were no exception. Apart from dispatching troops under the guidance of the general Erzhu Rong, the

magister militum

of the Bei Wei, she did nothing to solve the deep-seated hatred that was ripping the kingdom apart. By 528, she had given her lover most of the power at court while refusing to grant any to the young emperor Wei Xiaoming.

Wei Xiaoming, now eighteen, was old enough to fight back. He sent messages to Erzhu Rong, asking him to come back from the northern frontier and remove both the empress and her lover from power. Erzhu Rong started south to answer his emperor’s plea, but before he could reach Luoyang, the empress dowager poisoned her son.

She and her lover then appointed a two-year-old child to be the figurehead emperor. In response, Erzhu Rong and his army declared a cousin of the dead Wei Xiaoming to be the rightful emperor and crowned him in camp, on the move. When Erzhu Rong arrived at Luoyang, he sacked the city, captured the empress, and had both her and the child emperor drowned in the Yellow river. He then summoned two thousand of her officials and supporters to his headquarters and had them murdered, in an act that became known as the Heyin Massacre.

12