The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (3 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Between 312 and 330, Constantine imposes his will on the Roman empire and gives the Christian church a hand with its doctrine

O

N THE MORNING

of October 29, 312, the Roman soldier Constantine walked through the gates of Rome at the front of his army.

He was forty years old, and for six years he had been struggling to claim the crown of the

imperator

. Less than twenty-four hours before, he had finally beaten the sitting emperor of Rome, twenty-nine-year-old Maxentius, at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Constantine’s men had fought their way forward across the bridge, toward the city of Rome, until the defenders broke and ran. Maxentius drowned, pulled down into the mud of the riverbed by the weight of his armor. The Christian historian Lactantius tells us that Constantine’s men marched into Rome with the sign of Christ marked on each shield; the Roman

*

writer Zosimus adds that they also carried Maxentius’s waterlogged head on the tip of a spear. Constantine had dredged the body up and decapitated it.

1

Constantine settled into the imperial palace to take stock of his new empire. Dealing at once with Maxentius’s supporters, he ordered immediate but judicious executions: only Maxentius’s “nearest friends” fell victim to the new regime.

2

He dissolved the Praetorian Guard, the standing imperial bodyguard that had supported Maxentius’s claim to the throne. He also packaged Maxentius’s head and shipped it south to North Africa, as a message to the young man’s supporters that it was time to switch allegiances. Then he turned to deal with his co-emperors.

His victory over Maxentius had given him a crown but not the entire empire. Thirty years earlier, his predecessor, Diocletian, had appointed co-rulers to share the job of running the vast Roman territories—a system that had spawned multiple lines of succession. Two other men currently held parts of the empire. Licinius, a peasant who had risen through the army ranks, had claimed the title of

imperator

over the central part of the empire, east of the province Pannonia and west of the Black Sea; Maximinus Daia, who had also clawed his way up from peasant birth, ruled the eastern territories, which were constantly threatened by the aggressive Persian empire.

*

Diocletian, an idealist, had designed his system to keep power out of the hands of any one man; but he had not reckoned with the drive to power. Constantine had no intention of sharing his rule. Nevertheless, he was too smart to open two wars simultaneously. Instead he made a deal with Licinius, who was not only closer than Maximinus but also less powerful: Licinius would become his ally. In return, Licinius, now nearing sixty, would marry Constantine’s half-sister, the eighteen-year-old Constantia.

Licinius accepted the deal with alacrity. In his first gesture of good faith towards his brother-in-law-to-be, he met Maximinus Daia in battle on April 30, 313—six months after Constantine entered Rome. Licinius had fewer than thirty thousand men, while Daia had assembled seventy thousand. But Licinius’s army, like Constantine’s, marched under the banner of the Christian God. It was a useful rallying point; Maximinus Daia had vowed, in Jupiter’s name, to stamp out Christianity in his domains, and the presence of the Christian banner pointed out that the battle for territory had become a holy war.

The armies met on the poorly named Campus Serenus, outside the city of Adrianople, and Licinius’s smaller army outfought Maximinus’s. Maximinus Daia fled in disguise, but Licinius followed him across the province of Asia and finally trapped him in the city of Tarsus. Seeing no escape, Maximinus Daia swallowed poison. Unfortunately, he indulged in a huge last meal first, which delayed the poison’s action. The historian Lactantius writes that he took four days to die:

[T]he force of the poison, repelled by his full stomach, could not immediately operate, but it produced a grievous disease, resembling the pestilence…. Having undergone various and excruciating torments, he dashed his forehead against the wall, and his eyes started out of their sockets. And now, become blind, he imagined that he saw God, with His servants arrayed in white robes, sitting in judgment on him…. Then, amidst groans, like those of one burnt alive, did he breathe out his guilty soul in the most horrible kind of death.

3

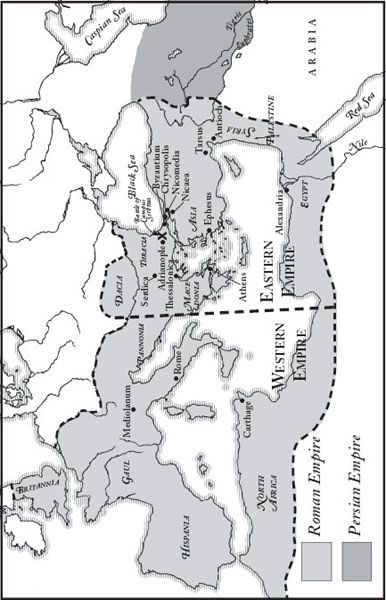

1.1: The Empires of the Romans and Persians

Nor was it the last horrible death. Licinius then murdered Maximinus Daia’s two young children, both under the age of nine, and drowned their mother; he also put to death three other possible blood claimants to the eastern throne, all children of dead emperors.

Constantine found it prudent to ignore this bloodshed. The two men met in Mediolanum (modern Milan) to celebrate Licinius’s marriage to Constantia and to issue an empire-wide proclamation that made Christianity legal, which was highly necessary given that both men had now wrapped themselves in the flag of God in order to claim the right to rule.

In fact Christianity had been tolerated in all parts of the empire except the east for some years. But this proclamation, the Edict of Milan, now spread this protection into Maximinus Daia’s previous territories. “No one whatsoever should be denied the opportunity to give his heart to the observance of the Christian religion,” the Edict announced. “Any one of these who wishes to observe Christian religion may do so freely and openly, without molestation…. [We] have also conceded to other religions the right of open and free observance of their worship for the sake of the peace of our times, that each one may have the free opportunity to worship as he pleases.” Property which had previously been confiscated from Christians was supposed to be returned. All Christian churches were to be turned over to Christian control. “Let this be done,” the Edict concluded, “so that, as we have said above, Divine favor towards us, which, under the most important circumstances we have already experienced, may, for all time, preserve and prosper our successes together with the good of the state.”

4

The “good of the state.” In Lactantius’s accounts, Constantine is a servant of the Divine, and his enemies are brought low by the judgment of God Himself. Eusebius, the Christian priest who wrote Constantine’s biography, reflects the same point of view: Constantine is the “Godbeloved,” bringing the knowledge of the Son of God to the people of Rome.

5

Eusebius was Constantine’s friend, and Lactantius was a starving rhetoric teacher until Constantine hired him as court tutor and changed his fortunes. But their histories are motivated by more than a desire to stay on the emperor’s good side. Both men understood, perhaps before Constantine had managed to articulate it even to himself, that Christianity was the empire’s best chance for survival.

Constantine could deal with the problem of multiple emperors; he had already eliminated two of his three rivals, and Licinius’s days were numbered. But the empire was threatened by a more complex trouble. For centuries, it had been a political entity within which provinces and districts and cities still maintained their older, deeper identities. Tarsus was Roman, but it was also an Asian city where you were more likely to hear Greek than Latin on the streets. North Africa was Roman, but Carthage was an African city with an African population. Gaul was a Roman territory, but the Germanic tribes who populated it spoke their own languages and worshipped their own gods. The Roman empire had held all of these dual identities—Roman and

other—

together, but the centrifugal force of the

other

was so strong that the borders of the empire were barely containing it.

Constantine didn’t put the cross on his banner out of an attempt to gain the loyalty of Christians. As the Russian historian A. A. Vasiliev points out, it would have been ridiculous to build a political strategy on “one-tenth of the population which at that time was taking no part in political affairs.”

6

Nor did Constantine suddenly get religion. He continued to emboss Sol Invictus, the sun god, on his coins; he remained

pontifex maximus

, chief priest of the Roman state cult, until his death; and he resisted baptism until he realized, in 336, that he was dying.

7

But he saw in Christianity a new and fascinating way of understanding the world, and in Christians a model of what Roman citizens might be, bound together by a loyalty that transcended but did not destroy their own local allegiances. Christianity could be held side by side with other identities. It was almost impossible to be thoroughly Roman and also be a Visigoth, or to be wholeheartedly Roman and African. But a Christian could be a Greek or a Latin, a slave or a free man, a Jew or a Gentile. Christianity had begun as a religion with no political homeland to claim as its own, which meant that it could be adopted with ease by an empire that swallowed homelands as a matter of course. By transforming the Roman empire into a Christian empire, Constantine could unify the splintering empire in the name of Christ, a name that might succeed where the names of Caesar and Augustus had failed.

Not that he relied entirely on the name of Christ to get what he needed. In 324, Licinius provided Constantine with the perfect excuse to get rid of his co-emperor; the eastern ruler accused the Christians in his court of spying for his colleague in the west (which they undoubtedly were) and threw them out. Constantine immediately announced that Licinius was persecuting Christians—illegal, according to the Edict of Milan—and led his army east.

The two men met twice: the first time near Adrianople, the site of Licinius’s own victory against the former eastern emperor Maximinus Daia, and the final time two months later, on September 18, at Chrysopolis. In this last battle, Licinius was so thoroughly defeated that he agreed to surrender.

8

Constantine spared his life when Constantia pleaded for him, instead exiling him to the city of Thessalonica.

Constantine was now the sole ruler of the Roman world.

H

IS FIRST ACTION

as solitary emperor was to guarantee the unity of Christian belief. Christianity would not be much help to him if it split apart into battling factions, which it was in danger of doing; for some years, Christian leaders in various parts of the empire had been arguing with increasing stridency over the exact nature of the Incarnation, and the quarrel was rising to a crescendo.

*

The Christian church had universally acknowledged, since its beginnings, that Jesus partook in both human and divine natures: “Jesus is Lord,” as J. N. D. Kelly remarks, was the earliest and most basic confession of Christianity. Christ, according to the earliest Christian theologians, was “indivisibly one” and also “fully divine and fully human.”

9

This was a little like simultaneously filling one glass to the brim with two entire glassfuls of different liquids, and Christians had wrestled with this paradox from the very beginning of their history. Ignatius of Antioch, who died in a Roman arena sometime before

AD

110, laid out the orthodox understanding in a series of balanced oppositions:

There is one Physician who is possessed both of flesh and spirit;

both made and not made;

God existing in flesh;

true life in death;

both of Mary and of God….

For “the Word was made flesh.”

Being incorporeal, He was in the body;

being impassible, He was in a passible body;

being immortal, He was in a mortal body;

being life, He became subject to corruption.

10

But other voices offered different solutions. As early as the second century, the Ebionites suggested that Christ was essentially human, and “divine” only in the sense that he had been selected to reign as the Jewish Messiah. The sect known as Docetists employed Greek ideas about the “inherent impurity of matter”

11

and insisted that Christ could not truly have taken part in the corruption of the body; he was instead a spirit who only

appeared

human. The Gnostics, taking Docetism one step further, believed that the divine Christ and human Jesus had formed a brief partnership in order to rescue humankind from the corrupting grasp of the material world.

†

And while Constantine and Licinius fought over the crown, a Christian priest named Arius had begun to teach yet another doctrine: that since God was One, “alone without beginning, alone true, alone possessing immortality, alone wise, alone good, alone sovereign,” the Son of God must be a created being. He was different from other created beings, perhaps, but he did not share the

essence

of God.

12