The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (5 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

To the shock of both kings, the smaller Jin force triumphed. With that defeat, Fu Jian’s bid to reunify China was over. His fledgling Chinese-style government had never been firmly established; his empire was held together with the sword, and each war of conquest strained the existing government a little bit more. “You have had so many wars lately,” one of his advisors had warned him before the invasion of the Jin, “that your people are becoming dissatisfied, and hate the very idea of fighting.” Once defeated, Fu Jian began to lose territories to rebellion and revolt, one at a time. Two years after his loss at the Fei river, Fu Jian was strangled by one of his own subordinates.

13

The strangler was named Tuoba Gui. Like Fu Jian himself, he was of northern stock; his ancestors were nomads of the Xianbei tribe, and the Tuoba family name testified to his “barbarian” origins. His own native state, the Dai state, had been conquered by Fu Jian ten years earlier; his grandfather had been its prince until Fu Jian annexed the state as part of his growing northern empire.

Now Tuoba Gui declared Dai’s independence. He changed its name from the Xianbei “Dai” to the Chinese “Bei Wei,”

*

and he changed his own family name from the Xianbei “Tuoba” to the Chinese “Yuan.” With his Chinese identity firmly in place, he then began his own campaign to conquer and unify the north.

Meanwhile the Jin army faced another challenge on its other frontier. Around 400, a pirate named Sun En began to recruit a navy, finding his crew among the sailors and fishermen who lived along the coast.

14

For two years, the pirate fleet sailed along the shore, raiding, burning, and stealing, earning the name “armies of demons” from the shore-dwellers. The Jin emperor put the duty of crushing the rebellion into the hands of his generals, who managed to defeat the demon army in 402—and who, in the process, gained more and more power for themselves.

The weakness of the eastern Jin throne, the increasing chaos along its northern frontiers, and the constant shifts in power in the north: China was in constant flux. A monastic movement began to gather force, giving those who followed it a way to remove themselves completely from the disorder that surrounded them.

The monastic impulse in Buddhism went all the way back to the Buddha himself, who is said to have established the first community of monks so that the “path of inner progress” could be followed without distraction.

15

The monasticism of the early fifth century was centered around the teachings of the newly developed Amitabha sect. By 402, two revered monks—the native Hui-yuan and an Indian monk named Kumarajiva—were spreading teachings of the Amitabha, the “Buddha of Shining Light,” who lived in the Western Paradise, the Pure Land, “a sphere without defilement where all those who believed in the Buddha were to be reborn.”

16

Compared with the nasty uncertain present, the Western Paradise was a particularly lovely place; and just as the Western Paradise was far, far away from the battling northern kingdoms and the failing Jin, so the monastic communities that began to grow in the early fifth century were far, far removed from any involvement in court politics. To join a monastic community was to renounce the world and give up all ownership of private property: to cut all ties of interest and ambition that bound you to the culture, the society, or the kingdom on the outside of the monastery. But monasticism also provided a refuge. You might give up the chance of bettering yourself—but in exchange, you gained peace.

The followers of the Amitabha had nothing to do with earthly power;

Hui-yuan rarely even left the monastery, and his students joined him in escape from the world.

17

Their practice was entirely different from that of the Christians in the west. There, Christianity had begun to serve the needs of the emperor; but in the land of the Jin, Hui-yuan argued, successfully, that Buddhist monks should be exempt from the requirement to bow to the emperor. They had chosen to exist in a different reality, where neither the battles in the north nor the warring in the south had any real importance.

TIMELINE

2

ROMAN EMPIRE | CHINA |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Between 319 and 415, the Guptas of India conquer an empire and resurrect Sanskrit to record its greatness

W

HILE THE

J

IN

were trying to re-create themselves in their shrunken domains, while Constantine ruled from his new city on the Black Sea, India was a sea of battling subkingdoms and tribal states. No religion, or idea, or emperor united the patchwork of tiny countries. The Mauryans, the last dynasty to claim a large part of the subcontinent as their own, were long gone. The north of India had been conquered and reconquered by wave after wave of foreigners: Greeks, central Asians, Parthians.

1

Unified rule had lasted a little longer in the south, where a dynasty called the Satavahana had managed to keep control over the Deccan, the desert south of the Narmada river. But by the third century, the Satavahana empire too had collapsed, giving way to a series of competing dynastic families. Even farther south, a line of kings called the Kalabhra was slowly building a more lasting dynasty that would hold power for more than three hundred years and swallow the entire southern tip of the subcontinent; but this kingdom left few inscriptions and no written history behind it. Throughout the rest of India, small states stood elbow to elbow, none of them claiming much more territory than the next.

2

In 319, a very minor king of one of those small jostling states passed his throne to his son. We know the name of the father, Ghatokacha, but it is not entirely clear where his original territory lay—possibly in the ancient kingdom of Magadha, near the mouth of the Ganges, or perhaps a little farther to the west.

Ghatokacha’s single most important accomplishment in life was to make a match between his son, Chandragupta, and a royal princess from the Licchavi family, which had once ruled a small kingdom of its own and still controlled land to his north.

3

So when Chandragupta inherited the throne from his father in 319, he had a little bit more than most other petty Indian kings: he had not only his own kingdom but also the alliance of his wife’s family. This proved just enough. He began to fight, and over the next years he conquered his way from Magadha through the ancient territories of Kosola and Vatsa, building himself a small empire centered on the Ganges. As a reward he gave himself the title

maharajadhiraja,

“Great King of Kings” (a claim that somewhat anticipated the reality).

4

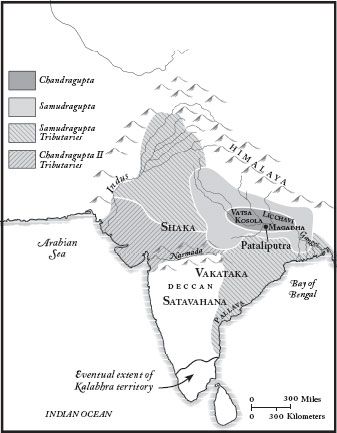

In 335, Chandragupta died and his crown went to his son Samudragupta. In Samudragupta’s hands, the little empire reached the critical mass that it needed in order to spread across the Indian countryside. Over the forty-five years of his reign, Samudragupta expanded his empire outwards in an irregular circle from his father’s possessions, encompassing almost all of the Ganges river in his kingdom. He also campaigned his way south, into the land of dynasties that had not yet come to their full strength. These dynasties (the Pallava on the southeastern coast, the Satavahana in the Deccan, the Vakataka, just to the west) were not quite powerful enough to keep Samudragupta out, and were forced one by one to pay him tribute.

Ruling from his capital city Pataliputra, at the great fork in the Ganges river, Samudragupta carved the names of his conquests on one of the ancient stone pillars erected long ago by Asoka the Great himself. Asoka had scattered these pillars around his own empire, using them for inscriptions later known as the Pillar Edicts; Samudragupta inscribed his own victories right over top of Asoka’s words. Samudragupta

needed

to connect himself, explicitly, with the glorious past. He was facing an enormous challenge: holding together a geographically far-flung empire populated by lots of minor warleaders, kings, and tribal chiefs who were stubbornly holding on to their own power, their own bloodlines, their own identity. Constantine had tackled this same problem by gathering his empire together under the banner of the cross, but Samudragupta had a two-prong strategy instead. First, he did not insist on the same power and control that Constantine asserted for himself. He called himself “conqueror of the four quarters of the earth,”

5

but the larger the boast, the smaller the truth. Samudragupta did rule over more land than any Indian king before him, but he was not the master of his empire. Most of the “conquered” land was not folded into his empire; to the north and the west, he wrung tribute money out of the “conquered” kings and then pulled his armies back and let them rule their territories, as before, with only nominal acknowledgment of his victory. He did not even attempt to conquer the stubbornest of the independent strongholds: the lands of the Shaka, which lay in western India and were governed by the descendents of Scythians, roaming nomadic tribes from north of the Black Sea.

The land directly under Samudragupta’s rule was nothing to sneeze at; it was, in fact, the biggest Indian empire since the collapse of the Mauryans four centuries earlier. But in the days of their most powerful king, Asoka the Great, the Mauryans had controlled almost the entire subcontinent. By contrast, Samudragupta’s empire, barely a fifth of the land south of the Himalaya mountains, was a pale shadow of former glory.

Once Samudragupta counted his tributaries though—the surrounding kingdoms that had agreed to pay him off on an annual basis—his kingdom tripled in size. So he found it simplest to ignore the difference between empire and tributary land. As far as he was concerned, he had conquered his neighbors to the south and west. Had India been facing imminent outside invasion, this would not have worked. But, guarded for the moment by the mountains, Samudragupta had the luxury of lifting his hands away from the “conquered” lands. He could have a form of emperorship without the headaches thereof.

Thus, under the Gupta rule, India arrived at what is sometimes called a golden age, and sometimes the classical age of Indian civilization. The label points us towards the second part of Samudragupta’s strategy, already hinted at by his use of Asoka the Great’s old pillar: he made conscious use of nostalgia, trying to create from the past a core that would exert a gravitational pull on the far edges of his empire.

The Gupta kings had been turning towards the past for their power for some years already. In the decades leading up to Samudragupta’s reign, the ancient language Sanskrit had become more and more widely recognized as the language of scholarship, court, government, and even economics. Sanskrit had come down into India long ago, trickling across the mountains from the central Asian war tribes that had seeped into India (their relatives had gone east into Persia and become Persian). It had, as languages do, mutated, changed, and mingled with other languages: it had given birth to simplified “languages of everyday use” such as Magadhi and Pali, both so-called

prakrits

, or “common tongues.”

6

But, well into its mutation, the original archaic form of the language had made an unprecedented comeback. By

AD

300, Sanskrit was the language of public record; by the time of Samudragupta’s conquests, Sanskrit was also the language of the court and the preferred speech of philosophers and scholars.

7

The Hindu scriptures known as the Puranas, the law codes, the epic tales of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata: all were written in Sanskrit.

The keepers of Sanskrit were the

brahmans

, the educated Hindu upper class of Gupta society. Buddhism was alive and well in India: Buddhists were building monuments and carving caves, leaving their mark on the Indian landscape. But Sanskrit’s dominance shows that the brahmans were firmly at the top of the world, at least in northern India.

Which goes a long way to explain why the Gupta age, inaugurated by Chandragupta and brought to its peak by Samudragupta, is so often looked back upon as a golden age and the classical period of Indian culture. Romila Thapar points out that both of these terms are suspect, implying as they do an entire structure of historical understanding. A “golden age” is when “virtually every manifestation of life reached a peak of excellence,” and a “classic period” implies a certain height from which a culture declines. To discover either in the past first requires that historians define excellence and height: Hindu chroniclers defined them as both Hindu and Sanskritic. In those terms, the Gupta age was indeed golden.

8

In fact, the Guptas themselves were not exactly “Hindu,” since this is a name that encompasses an elaborate later system. They built Hindu temples and wrote their inscriptions in Sanskrit, but they also erected Buddhist stupas and supported Buddhist monasteries. Hinduism and Buddhism, both systems for understanding the world, were not yet enemies, and Samudragupta, content with nominal rule over his outskirts, had no pressing political need to enforce a rigid religious orthodoxy.

But the official inscriptions of the Gupta court were Sanskrit, and Samudragupta used Hindu rituals in conquest, in victory, as tools of his royal power. It was useful to him to ally his reign with a glorious past: a learned past, an honorable past, a past of victory. Nostalgia and conservatism marked Samudragupta’s reign.

And like so many movements of nostalgia and conservatism, his was based on a total misunderstanding of what had come before. The inscriptions of his victories are a case in point. Asoka’s conquests had pushed the Mauryan empire outwards to its greatest extent, but his campaigns had killed hundreds of thousands (particularly in the south), and once his kingdom was secure he had been overwhelmed with remorse and regret. Turning away from war and victory, he had spent the remainder of his rule pursuing virtue and righteousness. And as part of his penance, he had carved his guilt in Pillar Edicts throughout his land: “The slaughter, death and deportation of the people is extremely grievous,” he mourned, “…and weighs heavy on the mind.”

9

Samudragupta too wanted to be a great king; he hoped to set himself in line with Asoka the conqueror, carving his own accomplishments side by side with the victories of the Mauryan emperor. But he seems to have used the pillar without understanding the faint traces of the edict already on it. Unwittingly, he set his triumphs and his boasts of victory next to Asoka’s regrets and repentance.

10

W

HEN

S

AMUDRAGUPTA DIED

, sometime between 375 and 380, a brief struggle for the throne followed. Coins from the period show, not an orderly progression from father to son, but the interpolation of another royal name: one Prince Ramagupta. Two centuries later, the play

Devi-Chandra-gupta

(from which only a few paragraphs survive) suggested that Ramagupta schemed to kill his younger brother Chandragupta, namesake of the kingdom’s founder. The younger Chandragupta had carried out a daring offensive against the Shaka enemies to the west, infiltrating the Shaka court in woman’s dress and assassinating the Shaka king. This made him so popular that Ramagupta decided to get rid of him. Discovering the plot, Chandragupta stormed into the palace to confront his brother and killed him in the heat of anger.

11

3.1: The Age of the Gupta

Chandragupta became king as Chandragupta II in 380. Eight years after his accession, Chandragupta II added the Shaka to the list of Gupta tributaries. Like his great-grandfather, he also made an alliance: between his daughter Prabhavati and the Vakataka dynasty of minor kings in the western Deccan. This sideways strategy led to a partial enfolding of the Vakataka into the Gupta empire: Prabhavati’s husband died, not too long after their marriage, and Prabhavati became regent and queen, ruling the lands of the Vakataka under her father’s direction. Master of two more Indian domains, Chandragupta commemorated his new reach by giving himself the name “Vikramaditya,” “Sun of Prowess.”

12

Like his father, Chandragupta II never tried to assert much more than nominal control over the outlying areas of his empire; like his father, he refused to enforce a strict Hindu orthodoxy. The Chinese monk Faxian, on a pilgrimage to collect Buddhist scriptures for his monastery, arrived in India sometime between 400 and 412. He was struck by the peace and prosperity that this laissez-faire style of government brought:

The people are numerous and happy; they have not to register their households, or attend to any magistrates and their rules; only those who cultivate the royal land have to pay (a portion of) the grain from it. If they want to go, they go; if they want to stay on, they stay. The king governs without decapitation or (other) corporal punishments. Criminals are simply fined, lightly or heavily, according to the circumstances (of each case). Even in cases of repeated attempts at wicked rebellion, they only have their right hands cut off. The king’s body-guards and attendants all have salaries. Throughout the whole country the people do not kill any living creature, nor drink intoxicating liquor, nor eat onions or garlic.