The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (9 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Back in the Roman empire proper, the royal brothers were forced to make peace with their barbarian enemies. Valens gave up on conquering the Goths in 369 and swore out a treaty with their leaders; in 374, Valentinian made peace with the Alemanni king, Macrianus. But almost immediately, yet another barbarian war broke out.

The year before, Valentinian had ordered new forts built north of the Danube, in land that belonged to the Germanic tribe known as the Quadi. The Quadi were not much of a threat (“a nation not greatly to be feared,” Ammianus calls them), and when the fort-building began, they sent a polite embassy to the local commander, asking that it stop. The complaints were ignored; the embassies were sent again.

18

Finally the Roman commander, apparently unable to think of a better solution, invited the Quadi king to a banquet and murdered him. This atrocious mishandling of the affair so infuriated the Quadi that they joined together with their neighbors and stormed across the Danube. None of the Roman farmers who lived on the frontier were expecting the attack: the invaders “crossed the Danube while no hostility was anticipated, and fell upon the country people, who were busy with their harvest; most of them they killed, the survivors they led home as prisoners.”

19

Valentinian, furious with the incompetence of the commander who had started the fight, recalled Theodosius the Elder and his son Flavius from Britannia and sent them to the trouble spot. He arrived shortly after, breathing fire and promising to punish his wayward officials. But when he saw the devastation of his frontier with his own eyes, he was horrified. He decided to ignore the murder of the Quadi king and launch a punitive invasion instead. He himself led the attack; Ammianus says, disapprovingly, that he burned villages and “put to death without distinction of age” all Quadi civilians he could get his hands on.

20

In fact, his behavior suggests that he had lost touch with reality in some frightening way. He cut off a groom’s hand after the horse the groom was holding for him reared up as he tried to mount; he had an inoffensive junior secretary tortured to death because of an ill-timed joke. He even ordered Theodosius the Elder, who had served him so well in Britannia, put to death after Theodosius lost a battle, and exiled his son Flavius to Hispania. Finally, the Quadi sent ambassadors to negotiate for a peace. When they tried to explain that they had not been the original aggressors, Valentinian grew so enraged that he had a stroke. “As if struck by a bolt from the sky,” Ammianus says, “he was seen to be speechless and suffocating, and his face was tinged with a fiery flush. On a sudden his blood was checked and the sweat of death broke out upon him.” He died without naming an heir.

21

The western empire was temporarily without leadership, and the officers on the frontier hastily suspended all hostilities with the Quadi. Valens sent word that Valentinian’s son, the sixteen-year-old Gratian, should inherit the crown and reign as co-emperor with his little brother, four-year-old Valentinian II.

Gratian’s first act (one that showed amazingly good judgment) was to recall Flavius Theodosius, son of the dead Theodosius the Elder, from Hispania and to put him in charge of the defense of the northern frontier. Flavius Theodosius had learned to fight in Britannia, and he proved to be a brilliant strategist. By 376, a year after Valentinian’s death, he was the highest ranking general in the entire central province.

His skill was needed. The Romans had begun to hear rumors of a new threat: the merciless advance of nomadic enemies from the east, fearless fighters who slaughtered and destroyed, who had no religion, no knowledge of right and wrong, not even a proper language. All the tribes east of the Black Sea were in agitation. The Alans, a people who had lived for centuries east of the Don river, had already been driven from their land. The king of the Goths, himself a “terror to his neighbors,” had been defeated. Refugees were crowding to the northern side of the Danube, asking to enter the security of Roman territory.

22

The Huns had arrived at the distant edges of the western world.

To the Romans, who had never seen them, they were as frightening as earthquake and tsunami, an evil force that could barely be resisted. Historians of the time had no idea exactly where these frightening newcomers came from, but they were sure it was somewhere awful. The Roman historian Procopius insists that they were descended from witches who had sexual congress with demons, producing Huns: a “stunted, foul and puny tribe, scarcely human and having no language save one which bore but slight resemblance of human speech.”

23

The story isn’t original; Procopius borrowed it from the book of Genesis, which says that in the times of wickedness before the Great Flood, “the sons of God went to the daughters of men and had children by them.” The church fathers believed that this described the union of fallen angels—demons—who slept with human women and fathered children who brought great evil to the world. Now the Christian interpretation of history had been married to the threatening present: the Huns were not just barbarians, but demons out to destroy the Christians of the Roman empire, the kingdom of God on earth.

24

6.2: The Barbarian Approach

The Huns were still distant, though, and the immediate problem was what to do with the refugees. Valens received an official delegation of Goths asking permission to settle in the Roman land on the other side of the Danube. He had already been forced to make peace with the Goths, and now he decided to permit the immigration. In return, the newcomers could farm the uncultivated land in Thracia and provide additional soldiers for the Roman army (as other Gothic peoples who had settled in the empire had agreed to do).

25

With the dam of the Roman border breached, new waves of fleeing Goths poured across the Danube. The Roman officials who were in charge of the new settlers were quickly overwhelmed by the paperwork. Taxes were mishandled; money was misappropriated; the newcomers wiped out food supplies and began to go hungry. Within two years, Valens’s decision led, yet again, to war with the barbarians. An army of angry Goths stormed through Thracia, spreading a “most foul confusion of robbery, murder, bloodshed, and fires,” killing, burning villages, taking captives, and heading for the walls of Constantinople.

26

Valens set out from Antioch to go to the defense of his city; in the west, young Gratian started east to help his uncle. Before he could arrive with his reinforcements, the paths of Valens and the Goths intersected at the city of Hadrianople, west of Constantinople—a city named after Hadrian, the emperor who had built a wall against barbarians. On August 9, 378, Valens plunged into the battle among his men and was killed. Two-thirds of his army fell with him; the Roman soldiers were thirsty and starving after their forced march. Valens was not wearing the imperial purple, and his body was so badly disfigured that it was never identified. The ground, says Ammianus, was ankle-deep in blood. All during the next night, the people of Hadrianople could hear coming from the dark the wails of the wounded and the death rattles of the dying left on the battlefield.

The Goths laid siege to the city, but they had less experience with sieges than with hand-to-hand combat, and soon withdrew. They tried the same at Constantinople, and again found that they had no hope of breaking down the walls. So they withdrew; but the point had been made. The Roman empire was far from all-conquering. Earthquake and flood could wreck it; a distant band of barbarians could disrupt it; and a ragged band of exiles could bring down the emperor.

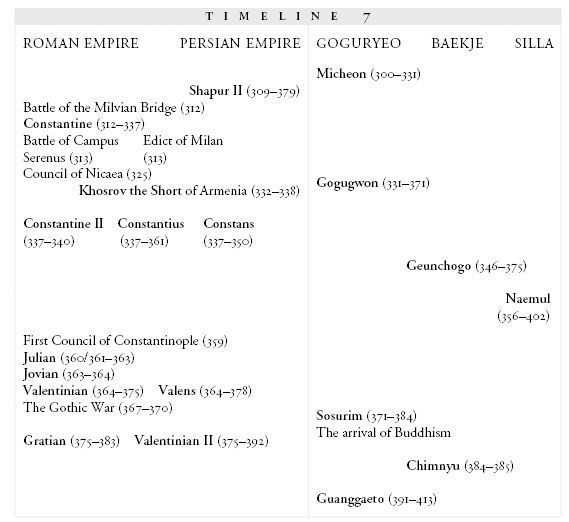

Between 371 and 412, Goguryeo adopts Buddhist principles and Confucian teachings and defeats its neighbors

A

LL THE WAY

to the east—beyond Constantinople, beyond Persia and India, past the empires of the Jin and the Bei Wei—another king struggled to recover from defeat. In 371, the young king Sosurim inherited the crown of the kingdom of Goguryeo, and with it a shattered and demoralized country. He had no firm foundation on which to rebuild; his army had been devastated, his officers killed in battle, his land laid waste.

His answer arrived in 372 in the hands of a monk.

The kingdom of Goguryeo lay on the peninsula east of the Yellow Sea. The ancestors of its people had probably come from the Yellow river valley long before, but the cultures of China and of the peninsula had been separate for centuries.

*

The people of the peninsula claimed an ancient and distinguished heritage. According to their own myths, the first kingdom in their land was Choson, created by the god Tan’gun in 2333

BC

—the era of the oldest Chinese kingdoms.

Before its collapse, the Chinese dynasty of the Han had captured the land across the north of the peninsula and had settled Chinese officials and their families there. In the south, three independent kingdoms formed: Silla, Goguryeo, and Baekje. Meanwhile, on the very southern tip of the peninsula, a fourth set of tribes—the Gaya confederacy—resisted attempts by its neighbors to fold it into the increasingly strong monarchies.

The kingdom of Goguryeo had always been the most aggressive and the most troublesome to the Han, who had hoped to keep the kingdoms south of their colonies from developing too much power: “By temperament,” the

Romance of the Three Kingdoms

remarked, “the people [of Goguryeo] are violent and take delight in brigandage.”

1

By the time the Han empire fell, its control over its lands in old Choson had shrunk to a single administrative district: Lelang, centered around the old city of Wanggomsong—modern Pyongyang.

7.1: Goguryeo at Its Height

Lelang outlasted its Han parent, surviving until 313. In that year, the ruler of the kingdom of Goguryeo, the ambitious and energetic king Micheon, pushed his way north and captured Lelang, adding it to his own territory and ousting the remaining Chinese forces. This made Goguryeo, under King Micheon, three times the size of any of its neighbors. It was the most powerful, the most dominant of the Three Kingdoms of Korea.

Which made it the biggest target as well. King Micheon died in 331, leaving his son Gogugwon on the throne. King Gogugwon was apparently not a warrior equal to his father; he followed a thirty-year policy of inaction, during which Goguryeo was sacked twice. In 342, armies from the Sixteen Kingdoms took thousands of prisoners and broke down the walls of its capital city, Guknaesong; in 371, the crown prince of Baekje led an invading army all the way up to Wanggomsong.

Shaken out of his withdrawal, King Gogugwon of Goguryeo came out in person to fight his neighbor. He was killed defending the Wanggomsong fortress. Baekje claimed much of Goguryeo’s territory as its own; and Sosurim, son of the defeated king, grandson of the great Micheon, was left with the shrunken shambles of Goguryeo.

Not long after he came to the throne, a Buddhist monk travelling from the west arrived at his court. This monk, Sun-do, brought with him gifts and Buddhist scriptures, along with the assurance that the practice of Buddhism would help to protect Goguryeo from its enemies. King Sosurim welcomed Sun-do and listened to him, and in 372 embraced the faith as his own. The following year, he established the T’aehak: the National Confucian Academy, patterned on Chinese principles.

2

Buddhism and Confucianism, essentially very different, formed a useful hybrid for Goguryeo. Sun-do taught Sosurim and his court that discontent, unhappiness, ambition, and fear were

samskrita

, conditions of the mind that were nonexistent: the enlightened student recognized that in fact there was no discontent, no unhappiness, no ambition, no fear. The kingdom of Goguryeo was itself

samskrita

, a conception that had no ultimate reality. Should King Sosurim and his officials truly understand this, they would be able to function in the world while recognizing (in the words of the Zen master Shengyan) that “the world and phenomena have no true existence.” Their decisions would not be shaped and tainted by the desire for gain, the desire for security, the desire for happiness.

3

Confucianism, on the other hand, accepted the reality of the physical world and taught its adherents how to live properly, with virtue and responsibility, within it. The principles of Buddhism gave Goguryeo a new unity, a spiritual oneness; the principles of Confucianism gave King Sosurim a tested framework for training new army officers, secretaries, accountants, and bureaucrats—everything a state needed to prosper. Buddhism was the philosophy of the monk, Confucianism the doctrine of the training academy.

And since Buddhism was not a creedal religion—one with a written statement of faith to which its believers assented—the two different ways of thinking existed, harmoniously, side by side. Buddhism, unlike Christianity, was never viewed by its practitioners as exclusive, a system that demanded the relinquishment of all opposing beliefs. So although King Sosurim made Buddhism his own, he did not make it an official state religion; this would have given it an exclusive authority, which made no sense within the Buddhist framework.

4

Goguryeo was no longer teetering on the edge of dissolution; King Sosurim was hauling it back from the brink, refounding it as a state. But it would be some time before the foundation he was building would be solid enough to support a campaign of conquest and expansion.

Meanwhile, Baekje remained the most powerful state on the peninsula, under the rule of Geunchogo, the king who had launched the invasion that killed Sosurim’s father. Baekje’s borders had swollen to encompass much of the south, and King Geunchogo (like his northern neighbor) needed to put into place practices that would keep the territory united under a single king. Never before had the crown of Baekje passed from father to son; one warrior after another had claimed it through strength. But a battle over the succession would, in all likelihood, result in Baekje losing territory, thanks to its leaders putting their energy into inside politics rather than outside expansion. King Geunchogo, protecting his conquests, declared that his crown should pass to his son. When he died in 375, his arrangements held firm. The throne passed first to his son and then (after his son’s early death) to his grandson Chimnyu.

5

In 384, the Indian monk Malananda, on a pilgrimage through China, came from the Jin to Baekje. When King Chimnyu heard of his approach, he came out to meet Malananda and took him into the capital city to listen to what he had to say. And, like King Sosurim, he too accepted the teachings of Buddhism.

6

For both kings, Buddhism held a sheen of antiquity, a flavor of ancient Chinese tradition. Both kings ruled over relatively new kingdoms, and in these kingdoms, all things Chinese were more desirable. Buddhism carried with it the resonance of centuries of inherited authority, a faint echo (by way of the Jin) of the distant and glorious past.

By the time Sosurim’s nephew Guanggaeto came to the throne in 391, the foundation laid by his predecessors was strong enough to support conquest; and the spread of Buddhist philosophy did nothing to convince Guanggaeto that he should forgo ambition and earthly gain. Barely a year after his coronation, Guanggaeto organized an attack against Baekje, which just decades before had seemed impregnable.

He had managed to make an alliance with the third kingdom on the peninsula, Silla. In 391, Silla was ruled by King Naemul, a man of forethought. He had already sent diplomats to the Jin court across the sea; now he responded to Guanggaeto’s overtures with friendship, happy to have an ally against the constantly encroaching Baekje.

The armies of Silla and Goguryeo joined together and stormed through Baekje. The kingdom was unable to resist for long; Baekje was overwhelmed by the combined armies of its neighbors. In 396, the king of Baekje handed over a thousand hostages to guarantee his good behavior, and agreed to pay homage to King Guanggaeto.

The rest of Guanggaeto’s rule was spent in conquests so extensive that Guanggaeto earned himself the nickname “The Great Expander.” Between 391 and 412, the Expander conquered sixty-five walled cities and fourteen hundred villages for Goguryeo, recovered the northern land that had been taken away decades before, and made Baekje retreat to the south. His deeds are carved on the stone stele that still stands at his tomb, the Guanggaeto Stele, the first historical document of Korean history: “With his majestic military virtue he encompassed the four seas like a spreading willow tree,” it tell us. “His people flourished in a wealthy state, and the five grains ripened abundantly.” His own words are preserved in the temple he built to commemorate his victories: “Believing in Buddhism,” the dedicatory inscription reads, “we seek prosperity.”

7