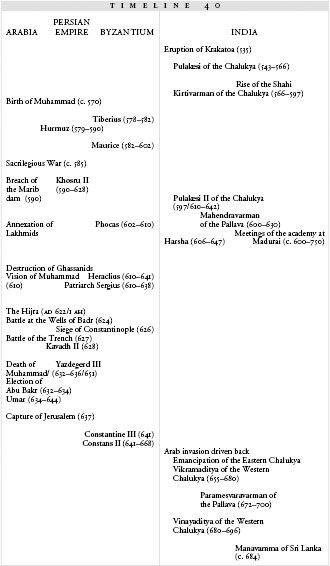

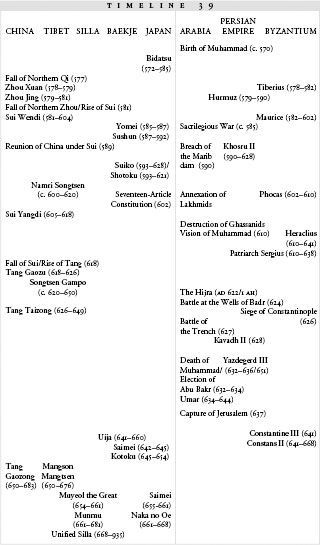

The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (40 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Not long after delivering the sermon, Muhammad grew ill and within a few days died.

He left no guide to his succession—no one appointed to receive his spiritual authority, no one to act in his role as ruler of the

umma

, no one to lead further campaigns. Perhaps he had no thought that a kingdom of Muslims would exist after his death. Certainly he had no intentions of leaving a hereditary kingship of some sort over his followers. His enormous achievement had a dark side: the identity of his followers was so closely bound up with his own person that the new Islamic community immediately began to spin apart. Old tribal loyalties, freed from the almost hypnotic effect of his personality, reasserted themselves.

Abu Bakr, his old friend and father of his young wife Aishah, was chosen as his successor by a gathering of Muslims in Medina. But the election was not uncontested; other Muslims, primarily in Mecca, wanted to appoint Ali ibn Abu Talib, Muhammad’s son-in-law, who was busy washing Muhammad’s body and mourning his death while the gathering was electing Abu Bakr.

It is not entirely clear what Ali himself thought of the situation. According to one version of events, Ali did not seriously argue with the selection of Abu Bakr as the next leader of the Muslim people; he retreated from the controversy, considered his position, and eventually offered his support to Muhammad’s friend. But other accounts suggest that he believed he should succeed his father-in-law, and disputed Abu Bakr’s election.

*

Either way, a number of Arabs resisted Abu Bakr’s leadership, with or without Ali’s support. Abu Bakr reacted not as a prophet, but as a general. He divided his own followers into eleven armed groups under eleven competent commanders, and assigned each one the task of subduing, by force, the areas where resistance to his leadership was making itself known.

12

The subjugation was successful; Abu Bakr became the sole heir of Muhammad’s power, the

Khalifat ar-rasul Allah

: the caliph, representative of the message of the prophet of God. (His original title, in fact, was “Caliph of the Messenger of God,” acknowledging his second-place status in the line of revelation.)

13

But the strike forces did much more than subdue rebellion. Later accounts called the resistance to Abu Bakr’s rule the

ridda

, the “apostasy,” and credited Abu Bakr with holding Muhammad’s conquests together. In fact, the eleven columns, under the leadership of Abu Bakr’s general and right-hand man, Khalid, fanned out and expanded the Islamic kingdom by conquering nearby tribes that had not yet fallen under Muslim domination. The conquest spread. Under Abu Bakr’s supervision, the rest of the peninsula fell, tribe by tribe and oasis by oasis, under the rule of the caliph. Within a year, Arabia was united behind him.

14

This left Abu Bakr at the head of an enormous armed camp that was not, as Medina and Mecca had been, necessarily convinced of the truth of Islam. It was, in the words of historian John Saunders, a kingdom filled with “recent, tepid, and unstable converts,” a powder keg with Abu Bakr sitting on the lid.

15

Abu Bakr decided to turn its energies outwards. Medina had prospered while grappling with outside enemies; nothing welded a people together like a war. In 633, he sent his general Khalid against the first enemy outside of the peninsula: the Persian empire. After the long bloody war with Byzantium, Persia had been further weakened by ongoing quarrels over the crown. Finally the grandson of the crucified Khosru II, Yazdegerd III (“a curly-haired man with joined eyebrows and fine teeth,” al-Tabari writes), had managed to take the throne by appealing to none other than Heraclius for help.

16

He had been king over the remains of Persia for only a year when Khalid and his Arab armies appeared on the other side of the Euphrates. At the same time, other Arab troops were making their way towards the Byzantine provinces of Palestine and Syria, under the command of four other generals.

The Byzantine troops put up a stronger resistance than Abu Bakr had expected, and just as Khalid was getting ready to attack the Persians, Abu Bakr recalled him and sent him westward to help out on the Palestinian front. Yazdegerd III had gotten a very brief reprieve, but at the expense of Heraclius. Byzantium, like Persia, had suffered from the long war; its soldiers were tired and depleted. The combined Arab troops defeated them in two large battles, capturing Damascus and moving through Palestine into Syria.

17

Just as the conquests were gathering momentum, Abu Bakr died. He had been caliph for two years and was an elderly sixty-one. He had been careful to leave strict instructions as to the succession; he wanted his son-in-law Umar to inherit his power, and the transition occurred in Mecca without chaos. On the battlefront, the armies pressed forward without halting.

Umar knew that his first task was to keep fighting. Al-Tabari tells us that when he was first acclaimed, he was addressed as “Caliph of the Caliph of the Messenger of God.” “Too long-winded,” Umar said. “When another caliph comes along, what will you call him? Caliph of the Caliph of the Caliph of the Messenger of God? You are the faithful, and I am your commander.” It was a moment of transition. As Commander of the Faithful, Umar was no longer merely Muhammad’s successor; he was the commander in chief of a new and expanding empire.

18

At this point, Heraclius realized that he had misjudged his enemy. This was not a bothersome raid—it was a serious and terrifying challenge to his power. To meet it, he put together a great coalition force: his own men, Armenian soldiers, Slavs from up north of the Black Sea, Ghassanid Arabs, and anyone else he could find. In this way, he managed to field an army of 150, 000.

His coalition met the invading Arabic forces at the Yarmuk river in Syria. Fighting went on for six entire days. The narratives of the battle are confused and contradictory, but they all end in the same way: the Byzantine army was routed, and Heraclius was forced to give up the provinces of Syria and Palestine, which he had just gotten back from the Persians. Jerusalem held out until the end of 637; Heraclius’s only victory was in managing to get the fragment of the True Cross out of the city and back to Constantinople before Jerusalem was forced to surrender to occupying Arab forces.

19

Meanwhile, Khalid turned back eastward and marched against Persia. He stormed all the way to Ctesiphon, which surrendered in the same year as Jerusalem. Yazdegerd survived the conquest of the capital and fled eastward, still alive, but without his capital city.

20

The conquests continued. In 639, Arab armies invaded the Byzantine holdings in Egypt, and by 640 all of Heraclius’s Egyptian land except for the city of Alexandria was under Arab rule. Heraclius himself was in increasingly poor health. He had brought the empire back from the brink of destruction, only to see it fall away again in the face of an unexpected and unstoppable eruption of force from the south. He was unable to put together a counteroffensive, and in 641 he had a stroke and died.

21

This left Constantinople in a bad position at a dreadful time. Heraclius had left the rule of the city to his son Constantine III, who was in perpetually poor health (he suffered from epileptic seizures); as insurance against Constantine III’s sudden death, he had also made his younger son co-emperor. This younger son, Heraklonas, was Constantine III’s half-brother—child of Heraclius’s second marriage to his own niece Martina.

This marriage had been very unpopular in Constantinople, which widely regarded it as a breach of biblical law. When Constantine III died a few months after his coronation (just as his father had feared), Heraklonas became sole emperor—and because he was only fifteen, his mother, Martina, became his regent. The army revolted, under the leadership of the general Valentinus, and took Heraklonas and Martina captive. Both were ritually mutilated before being sent into exile: Heraklonas’s nose was slit and Martina’s tongue cut out.

22

Mutilating a claimant to royal power was a ritual method of making him ineligible for rule. It had never been carried out in Constantinople before, and it wasn’t actually foolproof; Heraklonas was perfectly capable of ruling with a slit nose. But it seems to have played on the Old Testament regulation which stipulated that deformed priests could not minister in the temple.

*

The sudden appearance of ritual mutilation in Constantinople suggests that the emperor had become much, much more than a king: he was also some sort of guarantor of God’s favor, the channel of God’s grace. The people of Constantinople saw Heraclius’s incestuous marriage as a sin that was bringing judgment on them. As the unknown religion spread towards them from the south, they were desperate for a king who would bring salvation.

The options were limited, and the Senate chose Constans II, son of the dead epileptic Constantine III. He was only eleven, and on his accession he read to the Senate a statement that concluded, “I invite you to assist me by your advice and judgment in providing for the general safety of my subjects.”

23

The words had undoubtedly been provided for him. The Senate wanted Constans as the symbol of God’s continuing presence in the palace at Constantinople, but they intended to keep power for themselves.

Neither the symbol nor their power seemed to work. The empire continued to shrink both to the west and to the east. In 642, the year after Constans II was crowned, the Lombard king Rothari carried out a quick and savage conquest of the remaining Byzantine lands in Italy, leaving only the Ravenna marshes under the control of Constantinople. Of the few Byzantine troops left in Italy, eight thousand died in the fighting and the rest fled.

24

At the same time, Alexandria fell to the Arabs. Egypt was completely gone; Hispania had disappeared years ago; Italy was almost out of reach; North Africa was cut off from the rest of the empire. Only Asia Minor and the land around Constantinople itself remained in Byzantine hands.

The new caliph of the Arabs, Umar, had his eye on even wider conquests. He sent an army through the conquered lands of Persia, far to the east: all the way to the Makran, the bare land that lay past the far eastern Persian border. Almost a thousand years earlier, the Makran had killed off three-quarters of Alexander the Great’s army as they marched home from India. Apart from straggling settlements along the coast of the Arabian Sea where the sparse population subsisted on fish, there was no food or water in the Makran—just trackless sand and rock.

But the desert that had almost destroyed Alexander’s legendary army was familiar to the Arabs. They knew how to survive in the dry sands; and they pressed on through the Makran until, as al-Tabari tells us, they reached “the river.” They had come to the Indus, the edge of India itself.

25

Between 640 and 684, the Arabs turn back from the north of India, and the fractured south draws together

A

T THE

I

NDUS

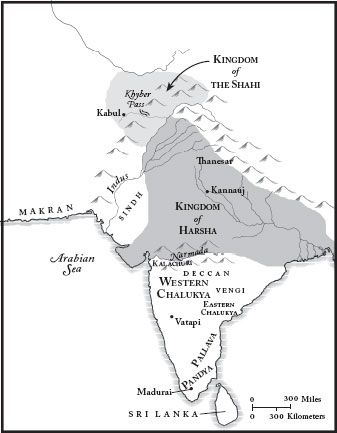

, the Arab armies found a gathered Indian army waiting for them. The “Makran army” and the king Rasil had assembled on the bank of the river, says al-Tabari, apparently in an effort to keep the Arabs from attempting to cross the water, and the “ruler of Sindh” had crossed over to join with him.

1

These were local Hindu kingdoms, independent of the huge realm ruled by Harsha a little farther to the east. The kingdom in the Makran and the kingdom in the Sindh had remained free from Harsha’s grasp, as had the kingdom of the Shahi, farther up to the north. The Shahi was a Buddhist kingdom that had existed in the northern mountains for a hundred years, in control of the Khyber Pass, its capital city at Kabul. They had adopted the Persian title “king of kings” (

shahi-in-shahi

) from their great neighbors, but Persian rule had never stretched all the way to the Indus. The Arabs had already come farther east than any army since Alexander’s.

2

The Shahi, not yet threatened by conquest, did not come south to assist the kings from the Makran and the Sindh, and the combined army was defeated. The Arabs pursued them back to the Indus river and drove them across it. Then, before crossing, the commander al-Hakam camped in the Makran and sent a messenger back to the caliph Umar, bearing a fifth of the spoils from the battle and asking what to do next.

According to al-Tabari, when the messenger arrived, Umar asked what kind of land the Makran was. He got a less-than-enthusiastic report: “It is a land whose plains are mountains,” the messenger told him, “whose only fruit is poor quality dates, whose enemies are heroes, whose prosperity is little, whose evil is long-lasting; what is much there is little; what is little there is nothing; as for what lies beyond, it is even worse.”

3

Umar decided that neither the Makran nor the Sindh were worth expending any more energy on. He wrote back to al-Hakam, forbidding him to pass over the river. The Arab armies turned back, and the eastern border of the growing Islamic realm remained, for the time being, in the Makran. In frustration, al-Hakam composed a verse in his own defense: “The army can place no blame on what I did, nor can my sword be blamed…. Were it not for my Commander’s veto, we would have passed over!”

4

40.1: Indian Kingdoms in the Seventh Century

Had Umar known that another great empire existed farther to the east, perhaps the Arabs would have pressed on. Harsha’s northern Indian kingdom was, by this time, richer and more powerful than the Persians. His defeat by the Chalukya, some years earlier, had halted his southern expansion at the Narmada river, but he had continued his wars of conquest until the entire north and northeast were under his control. Probably the king of the Sindh and the ruler of the Shahi were his tributaries, at least for a time; the two independent kingdoms lay as a useful buffer between his realm and invasion from the west.

Now in his late thirties, Harsha had reached his full strength and maturity. His capital, Kannauj, had grown into the premier city of northern India. He sent at least one diplomat to establish friendly relations with the Chinese court to his east. His taxes, reports the Chinese pilgrim Xuan Zang, were reasonable, and if he forced his people to work on roads or canals, he paid them for their time. This particularly struck Xuan Zang, who had grown up during the last years of the Sui and had seen the brutal completion of the Grand Canal.

5

Harsha’s sister still reigned beside him, and it is probably no coincidence that at this time a particular form of Hinduism that highlighted female power, or

shakti

, became more prominent. The worshippers who pursued this stream of Hinduism (which was one among many) were called Shaivas, followers of the god Shiva and of his consort, the Goddess. For them, wisdom flowed from Shiva through the Goddess, and then from the Goddess to the human world. Harsha himself wrote a play,

Nagananda

, in which Shiva’s goddess consort takes a leading role, resurrecting the dead son and heir of a grief-struck king to life and bestowing him with royal powers. In his youth, he had rescued his sister from a funeral pyre; in the play, the goddess lifts the dead young man from a funeral pyre and restores him to life.

6

Yet Harsha also honored Buddhism. In 644, the year after the Arab army turned back from the Indus, he held an enormous assembly in the capital city so that thousands would have the opportunity to hear Xuan Zang’s teaching; he had been much impressed by the monk and brought together (according to contemporary accounts) four thousand Indian monks to hear him. Towards the end of his life, he turned more and more towards Mahayana Buddhism and channelled more of the royal funds towards Buddhist monasteries. After a lifetime of war, he decreed that no living thing should be killed in his domain and that no one could eat meat for food.

7

Harsha died in 647. It is not clear that he ever married. Certainly he left no sons; his prime minister seized the throne but held it only for a matter of weeks. His empire fell back apart into minor battling kingdoms, and over the next decades the historical records disintegrate into chaos. He was the last Indian king who would be able to build an empire in the north; the next ruler to dominate northern India would come from the outside.

8

M

EANWHILE, THE

C

HALUKYA DOMAIN

to the south had fallen on hard times.

Pulakesi II’s death in 642 had started a thirteen-year civil war between his sons, which weakened the kingdom and allowed the Pallava enemy to invade. Pulakesi had driven the Pallava out of the northern part of their homeland, the Vengi, and had claimed it for himself; by the time his third son, Vikramaditya, managed to triumph over his brothers and claim the throne in 655, the Pallava armies had taken Vengi back. Vikramaditya had the throne, but he had lost his father’s conquests.

He had also lost the eastern part of the kingdom. Pulakesi had handed it over to his brother, Vikramaditya’s uncle, to govern as his viceroy. When Pulakesi died, the viceroy proclaimed himself king over the eastern territories. The Chalukyas had divided; from now on, the Western Chalukya king would govern at Vatapi, while the Eastern Chalukya king would reign over the coastal area.

At the same time, a shrunken ancient kingdom in the far southwest was experiencing a revival. The Pandya dynasty had ruled the coast of the south in distant times; the Greek and Roman geographers had known of them, vaguely, as traders and fishermen. Their power had dwindled, although the clan itself had survived. But in the last decades, the Pandya had again begun to establish themselves, first as governors of the city of Madurai, then as rulers of the surrounding countryside.

An account from a century later tells us that Madurai at this time was the headquarters of the Sangam, an academy where poets and their patrons gathered to write and read. Poems and epics written in Tamil, the language of the south Indians, were joined by a translation of the Mahabharata into Tamil. The academy met at Madurai for a century and a half, from around 600 until 750.

9

Vikramaditya of the Western Chalukya attacked the Pallava again in 670, fifteen years after coming to the throne. The Pandya, who had been forced to pay tribute to the Pallava king, were now drafted into the conflict as reluctant Pallava allies. Despite the reinforcements, the Chalukya army inflicted a painful defeat on the Pallava king, Paramesvaravarman I. The rivalry continued; four years later, the Pallava king retaliated by invading and sparking another giant confrontation. This time the fortunes were reversed; the Chalukya soldiers were defeated and driven back.

10

The Western Chalukya king Vikramaditya died in 680. His son Vinayaditya inherited his rule; although hostility with the Pallava kingdom continued, Vinayaditya managed to avoid major confrontations during his sixteen-year reign. Chalukya power now stretched across the center of the subcontinent, covering the former patchwork.

The Pallava, meanwhile, extended

their

power to the south. The island that lay off India’s southeastern coast, Sri Lanka, had at various times been claimed by south Indian rulers, but more often than not it played host to several different tiny, independent kingdoms at a time. In 684, a warrior named Manavamma asked the Pallava to lend him the soldiers he needed to make himself king of the entire island. Manavamma succeeded—but as payment for the soldiers, he was forced to pay tribute to the Pallava. Like the Chalukya kings, the Pallava dynasty had pushed its rule over the surrounding lands—and farther, down past the water, into the southern island.