The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (76 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

75.2: The Wall of Skulls (Tzompantli) at Chichen Itza.

Credit: Steve Winter/National Geographic/Getty Images

They left behind a fragmented landscape in which a melange of tribes and peoples mingled, blended, and fought. The Mixtec, hill-dwellers who had lived in scattered villages in the Oaxaca Valley, began to press in on the land vacated by the Maya. They also began to stake a claim to fields and valleys that had once been Zapotec; the bleedout of the great Zapotec city of Monte Alban had not destroyed Zapotec civilization, but the Zapotec territory had become a series of smaller settlements, each centered around the estate of an aristocrat or wealthy farmer who served as the de facto ruler of his community. The settlements were prosperous and stable, but vulnerable to Mixtec takeover and occupation.

14

With the collapse of the old cities, energy shifted to new sites. Northwest of ancient Teotihuacan, where squatters still lived in the ruins, the city of Tula began to grow.

The new peoples flooding into Tula, which sat on high ground some 150 miles from the Gulf coast, probably came from the southern valley now known as the Valley of Mexico. The newcomers were led by a prince named Topiltzin, and their entry into Tula set off a chain of events which became the Arthurian legend of Mesoamerica: a foundational myth shaping the memories and histories of the surrounding peoples for centuries.

*

The multiple stories of Topiltzin and the city of Tula are embroidered with conflicting details, and many of them have come down to us broken and incomplete. But they agree that Topiltzin became the king of Tula, and that he was worshipped as the son of a god during his lifetime. His father was said to be a divine conqueror, his mother a goddess, and Topiltzin himself was given the title “Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl,” high priest and earthly incarnation of the great god of wind and sky.

15

Tula was filled with craftsmen and merchants who specialized in the trade of obsidian. Its buildings lay over five square miles, and thirty-five thousand people lived within its walls. Its beauty, its security, and its wealth earned it an honorary title: the people of central Mesoamerica called it “Tollan,” a mythical name suggesting paradise, a place where every material need was met, where the gods had come down to teach the citizens craft and skill. The walls of its temples were carved with jaguars and eagles, clasping human hearts in their claws and talons; it was a paradise where human blood, the holy liquid that glued the seams of the cosmos together, was regularly shed in celebration.

16

Topiltzin ruled in Tula for over a decade, but trouble boiled under the surface. He had enemies within the city. One early story tells us that Topiltzin wanted to bring peace to Tula, and so insisted that winged creatures and reptiles—quail and butterflies, large grasshoppers and snakes—be sacrificed in the place of human captives. He was opposed by a demon in human form named Tezcatlipoca, who refused to allow the practice of human sacrifice to stop. This struggle over whether or not to shed human blood grew more savage, until Topiltzin decided to leave the city for good. He went into voluntary exile, travelling across the countryside until he reached the ocean.

17

There, on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, something happened. In some versions of the tale Topiltzin dies, beaten down by grief and exile, and is cremated by his followers. But in many others, he builds a raft and sails into the light; from the distant land of the sun, he will one day return and deliver Tula from its enemies.

Through the mesh of tales, we can see the sharp clash between the natives of Tula and the newcomers; Tezcatlipoca’s resistance is the act of a nobleman who has seen his own kinsmen supplanted, at the highest ranks, by outsiders. But we also see something more: an attempt to reconcile a real city with a mythical paradise. Tula/Tollan has a double existence in the Mesoamerican chronicles. It is a place of real walls and living people, but it is also a numinous city where the gods come to earth. Its inhabitants called themselves not Tulans, but “Toltecs”: inhabitants of blessed Tollan, beneficiaries of the gods. They were fortunate enough, they told themselves, to live in an earthly paradise, a physical city whose stones and walls somehow incorporated the beauty of the divine.

But as a physical city, Tula flourished for less than a century. Around 1050, large swathes of the city burned; the pyramids were pried apart by human hands, columns of ceremonial buildings toppled. The Toltecs, no longer residents of the sacred city but still clinging to their name, left the ruins and settled in various places, some joining the populations of nearby cities, others travelling farther south, where they mingled with the Mixtec.

At least one band of ambitious Toltecs went north, up into the Yucatán peninsula. Topiltzin and his people had come into Tula as outsiders; now these refugees from the fallen city of Tula broke into the largest Yucatán city, the flourishing metropolis of Chichen Itza, and seized control of its throne. It was not an easy transition. The conquest is depicted on reliefs and paintings throughout the city’s ruins, showing houses on fire, Toltec siege towers assaulting the walls, Toltec warriors rampaging through the streets, captives from the defeated population sacrificed to the gods.

18

Chichen Itza was already a sacred city. Pilgrims came from all over Mesoamerica to visit its sacred well, an enormous sinkhole nearly two hundred feet across and over a hundred feet deep. They threw offerings into it—carvings, jewels, keepsakes—and hoped for divine guidance from the gods. Once the city was under Toltec control, human sacrifices were also hurled into the sacred well. A new temple to the god Quetzalcoatl was built near the sinkhole, and its walls were adorned with the same images of heart-devouring eagles and jaguars that had decorated the sacred surfaces of Tula. The conquerors also built a

tzompantli

, a platform adorned with carved skulls, which held on it a display rack for the real skulls of sacrificial victims.

19

Topiltzin’s exile had allowed the old ways to flourish in Tula. The human blood spilled in the city’s temples had not kept the earthly paradise safe; the warriors and noblemen who had driven the peacemaker out had themselves been driven into exile. But in their new home, they once again began to shed blood, hoping that this time the sacred rites would keep disaster at bay.

Between 1002 and 1059, the emperors insist on their right to run church affairs, the Normans invade Italy, and the western and eastern churches split permanently apart

O

TTO

III,

KING OF

G

ERMANY

and Holy Roman Emperor, was having unexpected difficulties with his imperial plans. The words

Renovatio imperii Romanorum

appeared on Otto’s seal, along with a portrait of Charlemagne and Otto’s own name: the young emperor intended to restore the Roman empire, in the footsteps of his legendary predecessor and as a

Christian

empire.

Yet Rome itself was at the far edge of Otto’s proposed renewal. Despite the

Romanorum

on his seal, the empire he had in mind drew its identity from Christianity, not from its old relationship with the empire of the Caesars. It was centered in Germany, not in Italy; and as far as he was concerned, the pope was no more than his chaplain, meekly carrying out his orders.

1

This was exactly why he had appointed a pope who was both German and a blood relation. The choice of Gregory V (the papal name of his cousin Bruno) seemed eminently wise to the clergy in the Germanic kingdoms: “The news that a scion of the imperial house, a man of holiness and virtue, is placed upon the chair of Peter is news more precious than gold and costly stones,” wrote the Frankish monk Abbo of Fleury. But the Romans were indignant—not merely because the emperor had set a foreigner at the head of their city (although that was bad enough), but because Otto was so clearly dismissive of Rome’s importance. He returned to Germany in June of 996, just a few months after his coronation, turning his back on the Eternal City and leaving it in the hands of his flunky.

2

He was still only sixteen, after all, and his grandiose plans were accompanied by a complete lack of imagination. He had made his decrees, appointed his pope, and wrapped up his business, and he did not see why the Romans might be irate. But as soon as he was safely over the Alps, the Roman senator Crescentius rounded up a mob of indignant citizens. They vented their resentment over Otto’s high-handedness by chasing Gregory V right out of the city.

Gregory took refuge in Spoleto and sent a messenger to Germany, begging the emperor for help. Otto III did not hurry back to help his cousin; he had other important tasks to deal with. He did not start south until the middle of December 997, and even then he took his time, holding courts and audiences and pausing to celebrate Christmas on his way. By the time Otto III arrived in Rome, in mid-February of 998, Gregory V had been in exile for fourteen months, and Crescentius and the Roman churchmen had chosen a new pope of their own.

3

Angry though the Romans were, a glance over the wall told them that they had little chance of beating the German army. The ringleader, Crescentius, shut himself in a fortress that had been built long ago by the emperor Hadrian on the banks of the Tiber; the new pope, Johannes Philagathos, fled from the city; and the people of Rome opened the gates.

Otto III marched in and stayed for two months, which gave Gregory V enough time to return to the city and settle back in. He starved Crescentius out of the fortress, and his soldiers captured Johannes Philagathos on the run. Crescentius and twelve of his allies were beheaded and their bodies were hung upside down on the highest hill in Rome. Johannes Philagathos’s life was spared, but he was treated with even greater cruelty: his eyes were gouged out, his nose and ears were cut off, and he was ridden through the streets of Rome backwards on a donkey.

4

This sort of savagery was more Germanic than Christian, but to Otto’s mind the penalties made sense. Crescentius was punished as a traitor, Philagathos as a heretic. To defy the emperor’s right to direct church matters was to rebel against the very essence of his rule, the great mission of his life: to be

the

Christian monarch of the west.

He soon had a new ally to help him with this task. Gregory V did not live long after returning to Rome; he died suddenly and mysteriously, from causes that were never determined. Otto had already left the city, but when he heard of Gregory’s death he came back hastily to appoint a new pope. He chose his old tutor Gerbert, currently the archbishop of Ravenna, a priest who had already shown himself willing to cooperate with the emperor’s ambitions.

As pope, Gerbert took the name “Sylvester II.” This was not a casual choice of name; the first Sylvester had been bishop of Rome in the days of Constantine the Great. Although that Sylvester had done nothing of importance during his twenty-one-year bishopric (he hadn’t even attended the Council of Nicaea, sending two priests in his place), legends of great deeds had grown up around him. The

Acts of Saint Sylvester

, written well after his death, claimed that he had personally converted Constantine to Christianity, baptized him, and received the Donation of Constantine (itself a myth) from the emperor’s own hands.

5

Sylvester I, in other words, had shaped the emperor’s faith, helped him to create the Papal States, and worked with him to make the Roman empire Christian. The fact that he probably hadn’t done any of these things was irrelevant. As Sylvester II, the new pope intended to cooperate just as closely with the emperor in building a holy kingdom of their own.

Together, the two men started on their project of making the Roman empire into the Holy Roman Empire. Their method was to wind political and theological aims together into one binding cord, a strategy they first followed in dealing with the Magyars.

The Battle of Lechfeld was now half a century in the past. Under their prince Geza, the Magyars settled in the Carpathian Basin had travelled three-quarters of the way down the long road from warrior-state into a nation: the principality of Hungary. Geza had helped the process along by agreeing to be baptized. He may or may not have believed the creed he swore allegiance to, but his lip service to Christianity allowed Hungary to stake out its place as a Western nation, complete with parish system and archbishop.

Hungary was now ruled by Geza’s son Stephen, who, like his father, was known not as king of Hungary, but as grand prince of the Magyars. Otto and Sylvester planned to incorporate him into the Holy Roman Empire as a Christian king (and useful ally to the east). So Sylvester wrote him a papal letter. “Sylvester, bishop, to Stephen, king of the Hungarians,” the letter began, “greeting and apostolic benediction…. By the authority of omnipotent God and of St. Peter, the prince of the apostles, we freely grant the royal crown and name and receive under the protection of the holy church the kingdom which you have surrendered to St. Peter; and we now give it back to you and your heirs and successor to be held, possessed, ruled, and governed.”

The pope, not the emperor, had awarded Stephen the title of king. Normally, an emperor would extend recognition to a newly minted ruler, but this letter allowed Otto and Sylvester to clearly assert authority over the Hungarians, without the secular threat of swords behind it. “Your heirs and successors,” the letter concludes, “shall duly offer obedience and reference to us, and shall confess themselves the subjects of the Roman church.”

6

Stephen took this in a slightly different way than it was offered. To him, it seemed an acknowledgment of his independence as a sovereign Christian king. He accepted the letter and the jeweled cross that came with it, and ignored the implication that he would be subject not just to the pope, but to the pope’s patron, the emperor Otto.

The tendency of newly converted peoples to ignore the pope’s authority was only one of the difficulties facing the two men. Sylvester was not Roman, any more than the unpopular Gregory had been; he was Frankish, and with the emperor in the city, the Romans found themselves dominated by the active rule of a Frank and a German. In 1001, the people rioted.

Otto decided, on advice of his counselors, to leave the city; he did not have his entire army with him and was worried that the riots might escalate into out-and-out revolt. He and Sylvester set off north to Ravenna, where Otto III planned to gather troops and then return to Rome to straighten out its citizens. But while he was waiting for soldiers to arrive from Germany, he began to suffer from attacks of fever. These grew suddenly more intense. He was infected, his companions muttered, with “the Italian death”—some epidemic disease, described by his biographer Thietmar as “internal sores which gradually burst.” In January 1002, Otto III died. His soldiers took him back to Aachen and buried him next to Charlemagne. Otto was unmarried and left no heirs; he was twenty-two years old and had barely begun his adult life.

7

T

HE MAN WHO WON

Otto’s empire was Henry of Bavaria, son of old Henry the Quarrelsome. The German nobles elected him as King Henry II almost at once; the Italian cities refused to recognize his rulership at first, but after two years of fighting, Henry II had quelled the resistance in Italy and had himself crowned king of Italy in Pavia. Ten years later, when Henry II had proved himself a competent ruler of his two realms, he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Benedict VIII.

*

Otto’s seal had read

Renovatio imperii Romanorum

; Henry II’s proclaimed

Renovatio regni Francorum

. With Henry, the scrim covering the Germanness of the Holy Roman Empire became completely transparent. This was no kingdom of the past: it was a German empire, centered not on the holy city of Rome but on Henry’s own land.

8

Like the emperors who came before him, Henry II used lay investiture (the right of the king, as a layman, to award church positions) to keep the power of his empire centered on his own German circle. Like Otto, he gave offices and control over churches and monasteries to men who would be loyal to him. Like Otto, he treated the church like a faithful junior lieutenant of the emperor, rather than as an independent power; his particular method of keeping churchmen in line was to take a strong stand on clerical celibacy. Priests who married and had children were apt to pass land and responsibility down to them, creating lines of hereditary authority and wealth that became less and less dependent on the emperor. A childless priest, on the other hand, died and returned his post to the hands of those who had given it away in the first place.

Henry II was willing to give away posts, as long as the positions were going to return to his control in the future, and as long as the parishes in his domain accepted the priests he appointed without argument or question. Some churches were able to brandish charters at him that promised free elections, the right for the churches to choose their

own

bishop; Henry simply insisted that the phrase

salvo tamen regis sive imperatoris consensu

be added. Certainly these churches could choose their own bishops—as long as the imperial consent was granted to the results of the free election.

9

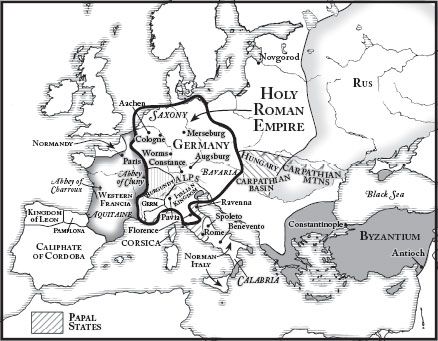

76.1: The Holy Roman Empire

In his ten years as Holy Roman Emperor, Henry II settled quarrels between monasteries, insisted that his own candidates benefit from the “free elections” of German bishops, and even tinkered with the liturgy; attending a service in Rome, he objected that the clergy did not always repeat the Creed during Mass, and insisted that it be inserted.

10

During his reign, the German priest Burchard, bishop of Worms, put together a twenty-volume collection of canon law. Anyone who resists the power of the emperor, reads one canon, is liable to excommunication, since the emperor’s power comes from God himself. No secular law, reads another canon, can be contrary to the law of God, which is above all royal laws. The innate contradiction stands without commentary—as do multiple contradictory canons that demand respect for the authority of the king and the primacy of the church, simultaneously, without resolution. The longer the Holy Roman Emperors ruled, the more glaring these unresolved contradictions became.

11

In 1024, Henry II died unexpectedly. He had been married for years, but he and his wife (a distant descendent of Charlemagne) had no children, and it was rumored that they had decided to be celibate, making their marriage into a spiritual union only. Whether or not this was true, it ended Henry’s dynasty, the Saxon dynasty of emperors, and left Germany, the Italian kingdom, and the Holy Roman Empire headless.

The German noblemen elected another of their own, Conrad II, the first emperor of a new dynasty: the Salians. Like Henry, Conrad II became king of Germany and then had to fight to assert himself in Italy. By 1027, he had control of both realms and was crowned Holy Roman Emperor on Easter of that same year; not long after, he had incorporated both Burgundy and Provence into the empire under his rule.

This rapid coronation as emperor was sheer boot-licking on the part of the pope, John XIX. John XIX was the brother of Benedict VIII, the pope who had crowned Henry II; the tenth-century Frankish monk Rodulfus Glaber tells us that when Benedict died, John used his considerable personal wealth to convince the Romans that he should ascend the papal throne next. The payments were substantial enough, apparently, to make up for the fact that John was actually a layman. With Henry II’s blessing, he had been run up through the ranks of the church in a single day and made pope before nightfall.

12