The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (42 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Uthman’s enemies surrounded his house, intending to kill him. He had ruled not as a prophet of God, but as Commander of the Faithful, and although he claimed divine sanction for his authority, the support of the faithful was his ultimate legitimization. He had lost it.

Standing on the walls of his house, he warned his assassins, “If you kill me, you will never pray together again, nor will God ever remove dissension from among you.” They answered, “You

were

worthy of authority, but since then you have changed.”

15

Then they broke into his house and stabbed him to death with iron-headed arrows, grasped like spears in their hands.

Rather than being buried at once, as Muslim custom dictated, Uthman’s body was thrown into a courtyard and left for three days. His family had to appeal to Ali (who had become the de facto leader of the city) to get permission to take the body. He was buried in a Jewish cemetery; no Muslim cemetery would allow him to be interred.

N

OT LONG AFTER

, a gathering of Ali’s supporters—rebels and many of the Quraysh who were not from the Banu Umayya clan—declared him to be the next caliph. He must have seen this coming. Nevertheless, he hesitated. Another voice was protesting, and it was a strong one: the voice of Aishah, widow of the Prophet and daughter of the first caliph Abu Bakr. She insisted that Ali had no right to rule, that the leadership of the Muslim community (widely dispersed as it was) should stay within the clan of the Umayyad, with its blood tie to Muhammad himself.

Ali found himself in an odd position. He did not particularly want to come up against the wife of the Prophet in conflict. On the other hand, her argument was a difficult one. The Banu Umayya clan was related to Muhammad, but distantly: the Banu Umayya and the Banu Hashim, Muhammad’s actual clan, had a common ancestor. Ali, by contrast,

was

Banu Hashim. He was not only Muhammad’s son-in-law but also his cousin; and his son Hasan was the grandson of the Prophet, child of Muhammad’s daughter Fatima.

Yet it was already known that Ali did not intend for the Quraysh tribe, to which both clans belonged, to continue to hold all the power for itself. In arguing that

Uthman’s

clan, rather than Muhammad’s own, become the “royal family” of the Islamic empire, Aishah was working to keep the tribe in power.

Ultimately Ali decided to accept the title of caliph. Later, he wrote to the Muslim governor of Egypt about his decision: “It could not even be imagined that the Arabs would snatch the seat of the caliphate from the family and descendents of the Holy Prophet, and that they would be swearing the oath of allegiance for the caliphate to a different person. At every stage I kept myself aloof from that struggle of supremacy and power-politics till I found the heretics had openly taken to heresy and schism and were trying to undermine and ruin the religion preached by our Holy Prophet.” He believed that establishing the caliphate in the Banu Umayya clan would make it unambiguously into a political position, destroying its close connection to Muhammad and his mission.

16

Yet to prevent this from happening, he would be forced to fight. Aishah and her supporters had already left Medina, heading for the city of Basra at the head of the Persian Gulf, where they hoped to gather more supporters for their cause. Ali gathered soldiers and followed them. In December of 656, six months after he had accepted the title, he met his enemies outside Basra’s walls in the Battle of the Camel. More Arabs had come down from Kufa to support him, and he won a quick victory. Aishah’s supporters were killed, and she was forced to return to private life.

17

But this first fight over the caliphate began a civil war: the

Fitna

, the “Trials.” Ali moved the seat of his caliphate from Medina to Kufa; Kufa was much more central to the newly conquered empire and was solidly behind him. He sent new governors, friendly to his cause, to take over the administration of the rebellious provinces. But one of the old governors refused. Muawiyah, founder of the navy, was still serving as governor of Syria, and Uthman had been his cousin. Instead of relinquishing his post, he threatened to fight back unless Uthman’s murderers were put to death.

18

Although Ali had not been directly involved in the bloodshed, the culprits were some of his strongest supporters; executing them was not an option. He wrote back to Muawiyah in defiance, accusing him of seeking justice (and even adopting Islam) for personal gain:

When you saw that all the big people of Arabia had embraced Islam and had gathered under the banner of the Holy Prophet, you also walked in…. By Allah, I know you too well to argue with you or to advise you. Apostasy and avariciousness have taken a firm hold of your mind, your intelligence is of an inferior order and you cannot differentiate what in the end is good for you and what is not…. You have also written so much about the murderers of Caliph Uthman. The correct thing for you to do is to take the oath of allegiance to me as others have done and present the case in my court of justice and then I shall pass my judgment according to the tenets of the Holy Qur’an.

19

Muawiyah had no intention of taking any oath. The two men traded increasingly testy messages (“I received your letter,” Ali wrote, “and to me it appears to be an idiotic confusion of irrelevant ideas”) until it became clear that only armed confrontation would sort out their difficulties.

20

They met in July of 657 on the upper Euphrates, each at the head of an army. Neither commander seems to have been comfortable with the idea of battle between two groups of Muslims: “Do not take the initiative in fighting,” Ali told his men, “let them begin it, and do not attack those who have surrendered.” When the battle did begin, the fighting dragged on inconclusively for three days. Finally Muawiyah’s men pulled back, impaled leaves of the Qur’an on the tips of their spears, and insisted that the two leaders work out their differences according to the laws of Islam. Ali’s soldiers joined in the demand, and the rivals gave in to the inevitable.

21

Negotiations, carried on through various intermediaries, were long-drawn-out and unsatisfactory for both sides. Eventually, Ali ended up with the title of caliph, ruling from Kufa; Muawiyah remained in Syria, without a title but ruling independently. Practically, the empire had been divided; its existence under one caliphate was a convenient myth.

Ali’s tenure as caliph remained troubled. The undercurrent of guilt over Uthman’s murder continued to run through his camp. In 658, a segment of his army broke away, accusing Ali of injustice because he had not avenged Uthman’s death. Injustice invalidated his charter; the unrighted wrong meant that he could not rule as true caliph.

Ali first tried to arbitrate with these rebels, whom his other troops called

Kharijis

, “Seceders.” Then he attacked them. He was unable to get rid of them, and the soldiers who were still loyal to him had little stomach for continually warring against their own kin. His power was dwindling.

22

In 661, a Khariji assassin murdered Ali in his camp. His remaining supporters tried to arrange the election of his son Hasan, the Prophet’s grandson, as caliph. But far more Arabs were arrayed behind Muawiyah. Hasan, a mature man in his forties who was not suicidal, agreed to come to a settlement with Muawiyah (and his sixty thousand soldiers). He would retire peacefully to Medina as a private person; in return Muawiyah promised that the caliphate would pass back to Hasan should Muawiyah die before him.

The Fitna had ended, and the Banu Umayya had risen to power: Muawiyah, the fifth caliph after the Prophet, was Umayyad. But like his predecessor, he was forced to fight constantly against rebels who resented his power.

The Islamic empire, which had once been centered around the community of the faithful, was beginning to look more and more like any other medieval empire: a conquered mass of peoples, some in constant rebellion, with ongoing struggles for power at the top and an ever-present tendency for the whole thing to fly apart. In turning those first Arab warriors outward, Abu Bakr had preserved the unity of the

umma.

But victory and conquest were already tearing at it from the inside.

Between 643 and 702, the emperor tries to leave Constantinople, the Lombards and the Bulgarians move towards nationhood, and North Africa falls to the armies of Islam

T

HE

L

OMBARDS OF

I

TALY

suffered no inconveniences from the Arab invasions to the east. In fact, the eastern wars made it possible for the Lombard king Rothari, elected in 636, to throw off almost all remaining tendrils of Byzantine control. While the emperor was occupied fighting with the armies of Islam, Rothari busied himself with systematically wiping out the emperor’s claim on all Italian lands—except for the enclave at Ravenna and the walled city of Rome itself.

These gains meant that it was time for the Lombards to mature away from their beginnings as conquering invaders, toward existence as a nation.

The Lombards were partly worshippers of the old Germanic gods, partly Arian Christians, partly Catholic Christians. A shared religion could have provided them with cohesion, but Rothari, a man of vision, wanted to give them more than cohesion. He wanted to give them statehood; so in 643 he created a written law, something they had never had. “This king Rothari,” writes Paul the Deacon, “collected, in a series of writings, the laws of the Langobards [Lombards] which they were keeping in memory only and custom, and he directed this code to be called the Edict.”

The Edict of Rothari, all 388 chapters of it, was written in Latin, but the laws were Lombard: Germanic spirit inhabiting Roman flesh. Pulling a man’s beard, an insult among Germanic warriors, drew a steep fine; those who deserted a comrade in battle were sentenced to death; a man who wished to transfer property to another had to do so in the presence of the

thing

, the assembly of freemen.

1

The laws helped to establish the borders of the Lombard kingdom, which to this point had been rather amorphous. “All

waregang

who come from outside our frontiers into the boundaries of our kingdom,” Rothari decreed, referring to foreign warriors settling in Lombard land, “ought to live according to the Lombard laws.” The Lombard lands in Italy were becoming Lombardy, a country for the wandering Lombards to call home.

2

As part of its transition into statehood, Lombardy was leaning towards orthodox Catholicism. The Arian Christianity of its leaders had been a marker of their Germanic blood, a leftover of the days when they were outsiders both to orthodoxy and to political power. Rothari’s successor, Aripert, became the first Catholic king of Lombardy, moving the Italian kingdom closer to the political mainstream.

In 661, when Aripert died, a brief war erupted between his sons. It ended with one son dead, the other in flight, and the crown in the hands of Duke Grimoald of Benevento, one of the semi-independent Lombard chiefs who was supposed to be loyal to the Lombard king.

All the way over in Constantinople, Constans II decided to intervene. Constans, fourteen when he came to the throne, had watched Egypt and North Africa fall to the Arabs at the same time that Italy was breaking away. Now, in 661, he was thirty years old, father of three sons, and nicknamed “Constans the Bearded” because of his remarkably heavy beard. He had assumed control of the empire, and the civil war in Lombardy gave him a plan. The Arab assault may have seemed unstoppable, but Italy was vulnerable; Constans II decided to leave Constantinople, set up his campaign headquarters in Tarentum, on the instep of the Italian boot, and reconquer the peninsula.

3

Constans II was not popular in Constantinople, which no doubt made the idea of re-establishing the throne in Rome even more attractive. But the plan reveals the extent to which the Byzantines still thought of themselves as Roman. Few of them had ever been to the Eternal City; no emperor had visited Rome in generations; Italy itself had long been out of Byzantine hands. Yet somehow Rome still occupied a place in the imagination. Constans II, heading for Rome, was out to recapture the glorious past.

By 663, Constans II was established in Tarentum and carrying on a reasonably successful war against the Lombard holdings in the south. A number of southern cities surrendered to him, and soon he was approaching the walls of Benevento, Grimoald’s hometown. King Grimoald, now at the Lombard capital Pavia, far to the north, had left one of his sons in charge of the city. The son sent to him for help, and Grimoald began the journey south with his royal army.

It must have been a large army, because Constans II was “greatly alarmed” at the news of Grimoald’s approach. He retreated, first to the coastal city of Naples (which had agreed to receive him; it had been loyal to Constantinople since Belisarius had taken it away from the Ostrogoths in 536) and then to Rome (the first visit of an emperor to the old city since Romulus Augustus had been dethroned). He stayed in Rome only twelve days, attended divine services conducted by the pope, raided the city for any remaining gold or copper ornaments he could melt down and use to fund his war, and then departed for Sicily. He landed on the island, went to Syracuse, and declared it to be his new capital. His intention to reclaim Rome hadn’t survived his first sight of the city. He had been imagining glories, but the real city—shabby, depopulated, demoralized—seemed beyond repair.

4

From Syracuse, he again began to launch attacks on the south of Italy. He ruled the island like an emperor of old: despotic, demanding, and imperious. He also sent for his wife and sons, a clear indication that he intended to stay in the west, away from Constantinople.

5

Thanks to his efforts, Byzantium kept control of the southern Italian coast. But his tyrannical behavior made him unpopular; his apparent desertion of New Rome, even more so. In 668, one of his house servants (undoubtedly part of a larger conspiracy) battered him on the head with a soap box until he died. His son Constantine IV was acclaimed in Constantinople and, profiting from his father’s poor example, remained there.

6

I

N

670,

TWO YEARS AFTER

Constantine IV’s accession, the Arab advance along the North African coast began again. At the same time, the Arab spread continued to the east. In the mountains north of India, Arab armies drove the king of the Shahi out of Kabul, his capital;

*

the Shahi kingdom kept control of the Khyber Pass but was forced to move its capital city east to Udabhandapura.

7

The multipronged expansion reached Constantinople in 674, when Arab armies laid siege to the city itself. The siege lasted four years, but Constantinople was able to continually refresh its supplies by sea, and conditions never became desperate. The Arab navy launched a final sea attack in 678, but the Byzantine ships made use of their famous “Greek fire,” a chemical concoction launched through tubes that kept burning even when it met the water, and finally the Arab ships withdrew—followed shortly after by the land forces.

8

While the emperor and his men were occupied with the defense of Constantinople, the Bulgarian tribes were given the space and time to expand.

Thirty years earlier, the emperor Heraclius had recognized the kingship of the Bulgarian chief Kubrat, north of the Azov Sea. Kubrat had died in 669, after a long reign during which he pushed the boundaries of Old Great Bulgaria up to the Donets and down to the Danube. Like a Frankish chief, he left the kingdom to his five sons jointly.

In his history, the

Chronographikon syntomon

, the ninth-century patriarch Nicephorus says that while on his deathbed Kubrat brought his sons around him and challenged each to break a bundle of sticks with his bare hands. When they all failed, he undid the bundle and broke the sticks easily, one by one. “Stay united,” he told them, “for a bundle is not easily broken.”

9

Instead, the five sons split apart almost at once. The second son, Kotrag, went north to the Volga and settled with his followers, where they became known as the Silver Bulgars. The third son, Asparukh, settled between the Dniester and the Prut river with over thirty thousand followers of his own. The fourth, Kouber, led a little band of Bulgarians first into Pannonia and then back toward Macedonia; the fifth son, Alcek, took his crowd all the way to Italy and formed a little Bulgarian enclave there. The oldest son, Bayan, remained in his homeland, ruling over the diminished population that remained once his brothers had left. The wisdom of Kubrat’s warning became clear: almost at once, the Khazars attacked Bayan, reduced his kingdom to rubble, and swallowed his territory, bringing an end to the original Old Great Bulgarian kingdom.

Constantine IV tried to emulate the Khazar khan; in 679, once he had recovered somewhat from the siege of Constantinople, he marched against Asparukh’s thirty thousand Bulgarians, who lay just on Byzantium’s western border. He was at first successful. But Theophanes says that he was forced to withdraw from the lines because he was suffering from gout, and that his troops became disheartened and fled.

10

The Bulgarian warleader Asparukh then made an alliance with the Slavic tribes nearby, fought his way down into Thracia, and generally caused a headache for the Byzantine armies on the northwestern border. By 681, Constantine IV had decided that he’d better make peace. He swore out a treaty with Asparukh, even agreeing to pay the Bulgars yearly tribute.

The Byzantine tribute payments and the conquests gave Asparukh more than a temporary settlement: his group of refugees, funded by Constantinople’s tribute payments, became the First Bulgarian Empire.

T

HE PEACE WITH THE

First Bulgarian Empire was followed, somewhat unexpectedly, by peace with the Arabs.

Muawiyah, the fifth caliph after the Prophet, died late in 680. He was followed by a string of short-lived caliphs: four within five years. Finally in 685, a caliph with the ability to both direct campaigns and administer the increasingly chaotic empire came to the throne: Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, who began his rule by ruthlessly squelching the Arabs who supported other candidates to the caliphate. It would take him six years to wipe out the opposition—six years of spending more energy fighting other Arabs, rather than the rest of the world—at a time when he was also dealing with famine and an outbreak of sickness, possibly a minor visitation of the plague, in Syria.

11

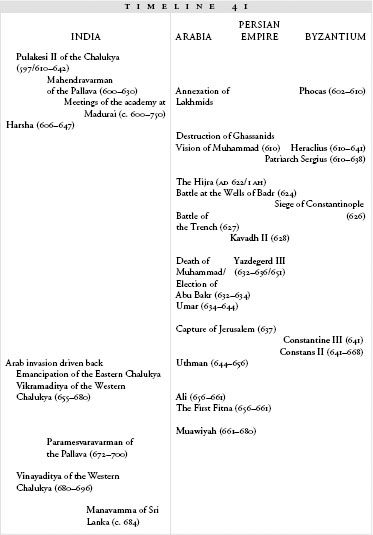

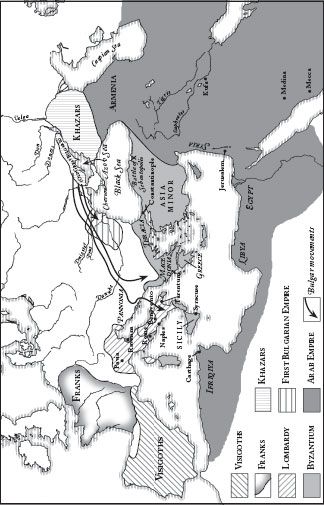

42.1: Byzantium, the Arabs, and the Bulgars

He sent to Constantine IV, offering to pay tribute in order to confirm a peace, and Constantine IV agreed to the terms. Shortly afterwards, Constantine IV died and left the throne of Constantinople to his son Justinian II.

12

Justinian II, only sixteen, inherited an empire that had slowly been reorganized over the previous decades into more efficient, more easily defensible divisions. Rather than the unwieldy provinces of the earlier empire, Byzantium was now divided into “themes.” Instead of being defended by troops dispatched from the capital, under the command of officers unfamiliar with their assigned territories, themes were defended by native soldiers: since Heraclius, the emperors had slowly been awarding land in the themes to soldiers in return for lifelong military service, and the tax system had been gradually reorganized so that the citizens in each theme paid their taxes directly to the local troops, rather than sending the money to the capital, where it might or might not get back to where it was meant to be.

The armies in each theme thus had strong motivation to protect it. Local loyalties, which always had the potential to rip an empire apart, had been directed into defending it. There were four themes in Asia Minor, another in Thracia, and two more in Greece and Sicily.

13

Justinian II also inherited the peace treaty with Abd al-Malik, which he agreed to renew. This gave Justinian time to get his bearings as emperor, while Abd al-Malik was able to finish putting down the rebellions against his caliphate. By 692, he had mastered his enemies and was, without competition, the only caliph of the Muslims.

Both men now wanted to break the treaty: al-Malik was ready to go back to conquering, and Justinian wanted to prove his worth as emperor. In late 692, al-Malik provided a useful excuse for both of them when he paid his tribute with Arab coins rather than Byzantine currency.

He had been working for some time to stabilize the financial affairs in the Islamic empire by creating a standard Arabic coinage. Justinian II at once announced the coins counterfeit and unacceptable, and declared war. He had hired, to reinforce his own army, thirty thousand or so Bulgarian troops as mercenaries: “He levied 30,000 men, armed them, and named them the ‘special army,’” Theophanes writes. He was “confident in them,” certain he could meet al-Malik in battle with success.

14

He was wrong. The Arab forces pushed into Byzantine land; when the armies met in 694 at the Battle of Sebastopolis, on the southern shore of the Black Sea, the Bulgarians cut and ran. Al-Malik had sent them money behind the scenes and promised them more if they would retreat once the battle began. The Byzantine troops were unable to hold the front without their allies and retreated. Al-Malik, flushed with victory, began a series of raids on the Byzantine coast.