The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (45 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

Empress Wei, who was not an original thinker, then tried to install her husband’s young son (by a concubine) as emperor so that she could be regent—just as the empress Wu had done three decades before. But the court was now familiar with this routine, and a palace rebellion led by the dead emperor’s sister and nephew ended with the young ruler imprisoned and the empress Wei, along with a score of her relatives and supporters, dead in the palace hallways.

The rebels then declared Ruizong, Zhongzong’s younger brother, to be the next emperor. Ruizong, now forty-eight, had (like his brother) already been emperor once; he had been coronated at the age of twenty-two, back in 684, and had ruled for six years under his mother’s thumb, until she had deposed him and declared herself emperor.

Ruizong had gone back to private life after his removal from the throne. He liked obscurity, and he did not want to re-enter the palace fray. But he finally allowed himself to be talked into returning to imperial life. In 710, he was recoronated; but by 712 he was fed up with court intrigue. When a comet appeared in the sky, he hailed it as an omen and abdicated.

He handed the crown over to his son, who became the emperor Tang Xuanzong. Tang Xuanzong, energetic and mature, began to reform the mess left in his father’s wake. He cut the government tax breaks for Buddhist monasteries, which forced a number of monks and nuns to return to civilian, tax-paying life; he reinstituted the Confucian system of choosing officials through a series of examinations, which weakened the power of the aristocratic families that tended to monopolize court positions through claiming the privilege of blood; he drove back the Tibetans and forced them to sue for peace; he stabilized the frontiers by setting up a series of command zones along the trouble spots and giving a military governor vast powers to deal with any difficulties; and he moved the capital back to Chang’an, which (thanks to his new tax policies and the relative peace of the frontiers) began once again to attract trade caravans from as far away as Constantinople.

13

Unlike the emperor Wu, he was able to pour his entire energies into ruling; none of it went towards transforming his power into legitimacy. He would rule for nearly half a century, bringing the Tang dynasty back from the edge of disintegration to the height of its glory, and earning himself the name “Brilliant Emperor.”

Between 705 and 732, Arab armies destroy the Visigoths, fail to capture Constantinople, and are turned back from Frankish land by Odo of Aquitaine (and Charles Martel)

T

HE LATEST GENERAL-TURNED-EMPEROR

of Constantinople, Tiberios III, sat uneasily on the throne. He had received bad news: the young emperor who had been dethroned and mutilated, Justinian the Noseless, had escaped from his prison in Cherson. He was at the court of the Khazars, plotting to get his throne back.

The Khazar khans had driven back the Arabs and conquered Old Great Bulgaria, which made the current khan, Busir Glavan, the strongest ally around. But the Khazars had also been allies of the legitimate Byzantine emperors since the days of Heraclius. In order to convince Busir Glavan to help him overthrow the man who currently wore the crown, Justinian the Noseless promised him something he didn’t yet have and couldn’t get by fighting: the chance to be kin to the Byzantine throne. He offered to marry Busir Glavan’s sister in exchange for help getting his throne back.

Busir Glavan agreed. Shortly afterwards, a secret message came from Tiberios of Constantinople: he would pay the khan handsomely to assassinate Justinian. Busir Glavan was a realist. Justinian would have to fight to get the throne back, and political alliance now was worth more than blood alliance with a man who might be emperor sometime in the uncertain future. He accepted Tiberios’s money and told off two Khazar soldiers to murder his new brother-in-law.

But he had underestimated Justinian. Warned by his wife that something was afoot, Justinian summoned the two soldiers to his house, probably under the pretense that he wanted to hire them as bodyguards. He welcomed them in and, when they were relaxed, strangled both of them with a cord. He then fled again, this time in a fishing boat, and escaped from the Khazar territory.

He managed to pilot the boat north into the Dniester river, crossing as he did so into the First Bulgarian Empire. Asparukh’s son Tervel now ruled over the Bulgarians, and he was an enemy of the Khazars, who had ravaged the original Bulgarian homeland farther east. Justinian convinced Tervel to support him with promises of alliance, cash, and the eventual marriage of his own daughter to Tervel; and in 705 Justinian was able to lead a Bulgarian army to the walls of Constantinople.

1

They spent three days trying to negotiate their way into the city before the ex-emperor lost patience. Familiar with Constantinople’s drainage system, he led his army in through a water main. They stormed the palace and seized Tiberios. Justinian reclaimed the throne and ordered Tiberios put to death. He also returned the favor of his mutilation by blinding the patriarch, who had supported Tiberios’s rule.

Justinian II’s second rule lasted six years, from 705 to 711. He was the only emperor who reigned after mutilation; he wore a silver nose to cover the hole where his own nose had been, and the people of Constantinople found it useful to pretend that the nose was real.

2

But his second reign proved to be nothing more than a single-minded hunt for those who had betrayed him the first time around. The six years became a reign of terror, as he ordered enemies and suspected enemies to be hung on the walls, trampled by horses in the arena, thrown in the sea in sacks, poisoned, and beheaded. In 711 the army rose up and murdered him.

3

No natural successor or strong general was able to pick up the reins of power. Between 711 and 717, three ephemeral emperors claimed and lost the throne of Constantinople.

But the armies of Islam, occupied elsewhere, did not immediately take advantage of this weakness. The caliph Abd al-Malik had died in 705, and his son Walid I was acclaimed as his successor. With Walid I in power, the Arab armies began to move off the North African beach.

The governor, Musa ibn Nusair, had been appointed to the Islamic province of North Africa, Ifriqiya. He in turn appointed as his military commander a Berber soldier named Tariq bin Ziyad, who had once been a slave but had earned his freedom through military service. Together, the governor and the new commander led an assault on the coastal city of Tangiers. They hoped that Tangiers could serve as a staging point for the Arab armies to cross the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea and move into the Visigothic kingdom of Hispania.

4

The realm of the Visigoths was ready to fall.

For nearly a century, the Visigoths had been struggling to keep their kingdom whole. An early hint of their difficulties had already appeared in 636, when the Fifth Council of Toledo—the gathering of priests, scholars, and officials that made the country’s laws—decreed that only a Gothic noble, of Gothic blood, could ever be king. In 653, the Eighth Council of Toledo added another stipulation: the king not only would be a Goth but also would be chosen by the “great nobility”: the Goths of the powerful families.

5

This wrote into law the old Germanic custom of electing warriors to be kings—a practice that most of the other Germanic kingdoms had slowly abandoned. It was a dynamic practice that suited a wandering people well, but in a settled country with customs and laws, the combination of election and royal prerogative was a volatile one. An elected president knows his power to be limited and his time brief, and approaches his new task circumspectly; an elected king comes into an administration with which he has no continuity and begins to exercise autocratic power. The chances to make enemies were endless.

The Toledo decrees reveal a country in which the hope of stability—of some continuity between administrations, of the continued pursuing of shared goals—lay not in laws, in constitution, or in the existence of a royal family, but simply in the assurance that the king would be of Gothic blood. But as the Arab armies approached, this stability was showing itself to be an illusion.

In 694, the king of the Visigoths, Egica, had appointed as co-ruler his eight-year-old son, Wittiza, and had followed this up with a coronation ceremony around 700, when Wittiza reached adulthood (at the age of fourteen or so). Egica was already unpopular because he had claimed some of the land designated for the use of the king as his own personal property—an act that erased the line between the king’s rights as a ruler and his rights as a private person. The coronation of Egica’s young son was a clear attempt to introduce dynastic right to the throne into the Visigothic succession. It had been resented both by the nobles who prized their right to choose a king and by the nobles who thought they had a chance to be chosen. But the desire to revolt against Egica’s presumption was temporarily quenched by an outbreak of plague, so severe that the capital city was deserted by anyone who could afford to get out. Egica and Wittiza left Toledo in 701, and Egica died shortly afterwards, possibly of the sickness.

Although we know little about Wittiza’s solo reign, one contemporary chronicle mentions that he returned the land his father had claimed to the “royal fisc,” transferring it from his personal ownership back into the service of the throne. He was young, but he must have seen the resistance to his father’s innovations.

6

The gesture did not save him. By 711, Wittiza had disappeared from the historic record; his fate remains a mystery, but another king, named Ruderic, sat on the throne with the support of the Gothic nobles. The events that follow are unclear, the accounts confused and contradictory. But mentions of two other kings in different parts of Hispania suggest that support for Ruderic was not unanimous among the Gothic nobles, and that civil war erupted. The system of election, meant to put competent kings on the throne while avoiding blood succession, broke down just at the moment that an attacking army was on its way.

7

The army was a mix of Arabs and Berbers commanded by the Berber general Tariq bin Ziyad. Coastal raids on southern Visigoth towns had already begun. Ruderic assembled what defense he could muster, but some sources hint that his competitors for the throne had already allied themselves with the invaders, possibly even assisting Tariq’s entrance into Hispania. If so, they had overestimated the goodwill of the newcomers. On July 19, 711, Tariq bin Ziyad and his troops met Ruderic at the Battle of Guadalete, and in a shattering defeat, Ruderic, his noblemen, and his officers were wiped out. “God killed Ruderic and his companions, and gave the Muslims the victory,” writes the Arab chronicler Ibn Abd al-Hakam, “and there was never in the West a more bloody battle than this.”

8

This brought an abrupt end to the Visigothic kingdom in Spain: not because the king was dead, but because almost the entire stratum of aristocrats, the men who held the right to elect the monarch, was wiped out. There was no more king—and, more damaging, no one who could claim the right to appoint one. No one had the authority to organize a resistance or to negotiate a treaty with the invaders.

For the next seven years, the Arab and Berber army fought its way across the country, conquering and negotiating with local officials. Tariq himself was recalled from Hispania after a single year, and the newly conquered territory—now known as the Islamic province of al-Andalus—was placed under the command of the governor of North Africa.

In 715, the caliph Walid I died, leaving as his legacy the Arab entrance into Europe. His younger brother Suleiman took up the caliph’s mantle and immediately refocused the energies of the Islamic armies on the Byzantine borders.

Byzantium was still suffering from turnover at the top of the chain of command. The third of three temporary and passing emperors, Theodosius III, sat on the throne.

*

He was a harmless tax official who had been elevated much against his will (in fact, Theophanes the Confessor says that he hid in the woods when he discovered that his soldiers were planning to acclaim him), and he had no stomach for facing the gathering Arab attack. When the armies at Nicaea proclaimed one of their generals, the Syrian Leo, as emperor, Theodosius abdicated with relief and went to a monastery, where he trained for the priesthood and eventually became bishop of Ephesus, a job much more to his liking.

9

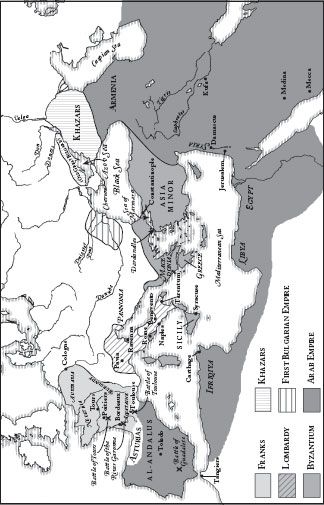

45.1: The Arab Advance

The soldier Leo, now Emperor Leo III, brought an end to the chaos in Constantinople. He prepared at once for an expected Arab assault, and within a matter of months the Arab ships, a fleet eighteen hundred strong, were sighted passing through the Dardanelles—the strait at the far end of the Sea of Marmara. They were under the command of the new caliph Suleiman. At the same time, Suleiman had sent a ground force of eighty thousand around through Asia Minor. The ships drew close to the city from the south just as the troops were arriving from the east.

10

The entrance into the Golden Horn, the harbor at Constantinople, was protected by a giant chain; the ground forces would have had to fight their way forward and lift the chain to allow the ships into the harbor. Before they could do so, Leo III launched an attack force of burning ships, set alight with unquenchable Greek fire, into the approaching fleet. The wind was with him. Hundreds of the Arab ships were set on fire and either sank or went aground.

Suleiman regrouped his remaining ships, at which point Leo III himself unhooked the chain closing off the Golden Horn and opened the harbor. “The enemy thought he wanted to entice them and would stretch [the chain] out again,” writes Theophanes, “and they did not dare to come in to anchor.” Instead they retreated, anchoring at a nearby inlet. Before they could reorganize their attack, two disasters struck them: a sharp and unusually severe winter suddenly descended (“For a hundred days crystalline snow covered the earth,” says Theophanes), and Suleiman grew ill and died.

11

His cousin Umar was proclaimed caliph in Damascus, the current capital of the Abbasid empire, as Caliph Umar II. A new admiral was sent from Egypt; when he arrived in the spring, the attack resumed. But Leo III had arranged a new treaty with the Bulgarians, and a Bulgarian army arrived in midsummer to help lift the siege.

Theophanes claims that twenty-two thousand Arabs died in the battle before the walls. Umar II sent word that the siege should be abandoned, and the Arabs “pulled out in great disgrace” on August 15, 718, and started home. Once again, Constantinople had resisted the Arab flood; it still lay inaccessible to the Islamic conquest, blocking the eastern path into Europe.

12

But the western path had proved much easier for the Arab armies. Almost no roadblocks had been flung into their way by the Visigoths. In 718, a flicker of resistance appeared; a Visigoth noble named Pelayo retreated into the northern mountains with his followers and declared himself king of a Christian kingdom. The kingdom of Asturias, tiny and poverty-stricken, survived repeated Arab attacks, thanks to its mountain defenses; but it did nothing to halt the Arab advance. Under al-Samh, the new governor of al-Andalus, the Islamic army reached the edge of the old Visigothic land and came within hailing distance of the Frankish land known as Aquitaine.

T

HE

F

RANKS, LIKE THE

V

ISIGOTHS

, like the Byzantines, had been suffering a slight crisis in leadership.