The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (82 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

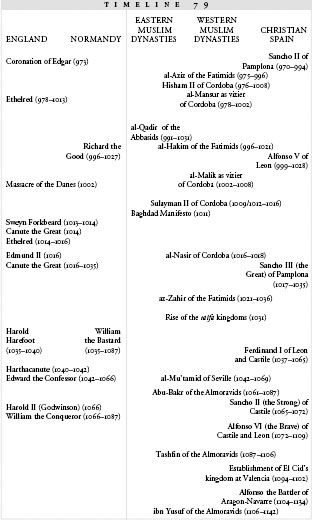

The old man died not long after, and Alfonso the Battler became king of Aragon and Navarre, Leon and Castile,

rex Hispania

. But he held Leon and Castile only through his wife, and their marriage was a disaster. Urraca was a grown woman in her late twenties, not a naive young girl. She had a four-year-old son from her previous marriage, and this child, not Alfonso the Battler, had the right to become the next ruler of Leon and Castile. She insisted on ruling her own part of the empire without her new husband’s help, going so far as to banish her old tutor because he referred to Alfonso the Battler as “king of Castile.” On top of the political problems, she simply didn’t like Alfonso; there was a “want of affection between the wedded pair,” says one chronicler. They quarrelled, and separated within a matter of months.

21

But Alfonso the Battler still claimed the title of king over the whole realm. During the next eight years, he fought a constant war with the Almoravid armies along the frontier. Urraca also sent the armies of Leon-Castile against the Almoravids.

Periodically, the estranged husband and wife also fought against each other; once Alfonso the Battler even captured his spouse and kept her for a while as a prisoner of war. The hostility between the Christian king and queen thwarted their attempts to fight the North African enemy; thanks to their decaying marriage, the Almoravids kept power a little longer.

Between 1025 and 1071, the empress Zoe crowns three husbands, and the Seljuq Turks make themselves an empire

B

ACK TO THE EAST

, eleventh-century Constantinople emerged from its self-absorption just in time to see a brand new enemy appear on the eastern horizon.

Basil the Bulgar-Slayer died in 1025; Constantine VIII, his young brother and heir, wore the sole crown of Byzantium for only three years. He was in his sixties and had spent his entire life hunting, horseback riding, and eating. He had no skill at governing and no experience as a soldier: “a man of sluggish temperament, with no great ambition for power,” Michael Psellus writes, “physically strong, but a craven at heart.” As a ruler, his greatest expertise was in “the art of preparing rich savoury sauces.” He had no sons and no heir; he had three daughters but had refused to let any of them marry, afraid that their husbands might try to unseat him. His reign was one of staggering irresponsibility.

1

When his last illness struck him in 1028, he was finally forced to arrange for a successor. The city governor of Constantinople, Romanos Argyros, was an experienced official in his sixties and also happened to be the great-grandson of Emperor Romanos I; Constantine suggested that Romanos Argyros marry his middle daughter, Zoe, and be crowned along with her.

Romanos Argyros was already married, and Zoe was forty-eight years old, but he didn’t turn down the chance to become emperor. He sent his wife to a monastery and proposed to the middle-aged princess. The two were married on November 12, 1028; three days later, Constantine VIII died, and Romanos Argyros and his new wife were crowned as Romanos III and Empress Zoe, rulers of Byzantium.

Romanos turned out to be a man with grand dreams and no talent for carrying them out. He gathered a huge army and marched against the Muslim border to the east; he raised taxes, hoping to make himself famous through enormous building projects; and he worked hard at siring an heir so that his dynasty would last forever. All of these projects backfired. The assault on the Muslim border ended with an embarrassing defeat; the new taxes made him hugely unpopular; and Zoe, nearly fifty, was well past childbearing years. Michael Psellus remarks that Romanos found it easier to ignore this unpleasant truth: “Even in the face of natural incapacity, he clung ever more firmly to his ambitions, led on by his own faith in the future,” the chronicler says. He hired specialists, doctors who claimed that they could cure sterility; he “submitted himself to treatment with ointments and massage, and he enjoined his wife to do likewise.” The specialists suggested to Zoe that she bejewel herself with magic charms whenever her husband visited her, which he did, often.

2

Ultimately, though, Romanos was forced to give up hope. He was too old to continue the sexual marathon he had instituted, and Zoe showed no signs of recovering from menopause. Discouraged, he abandoned her bedchamber altogether.

This was fine with Zoe. She had begun a torrid affair with the palace chamberlain, Michael the Paphlagonian, a handsome and pliable young man whose brother was a powerful palace eunuch. As Romanos’s popularity plummeted, Zoe decided that the elderly husband her father had lumbered her with had to go. She probably began to dose his food with poison; his courtiers noticed that he grew weak and short of breath, his face swollen and discolored. His hair began to fall out. One morning he was bathing alone when he slipped beneath the water and drowned. Apparently Zoe had expected the accidental drowning, because she married Michael the Paphlagonian on the evening of the same day and ordered the patriarch to crown him as emperor.

3

Although charming and clever, Michael was frequently ill (he was probably epileptic), and his short reign was a disaster on both political and personal fronts. It soon became clear that a puppet-master held his strings: not the empress, but Michael’s brother John, the powerful palace eunuch.

Many of the castrated men who served in Constantinople were slaves or prisoners, but Byzantium had its share of native-born eunuchs. Young boys with royal blood were often castrated to keep them from claiming the throne; even more commonly, rural parents with numerous sons would castrate two or three and send them off to the capital city to make their fortunes. They couldn’t all stay on the farm, and since eunuchs had no sons of their own and no ambitions to build dynasties, they had a distinct advantage at court.

4

John and Michael came from a farming family in Paphlagonia with five sons; John had been castrated, Michael spared. John’s competence and Michael’s beauty had secured both a place at court, and John, the more intelligent and driven of the two, had masterminded his brother’s affair with the empress. Now Michael was emperor, and John, nicknamed “Orphanotrophus” because he had charge of the official state orphanage in Constantinople, was the power behind the throne. Psellus, who as a boy met the eunuch in person, says that John Orphanotrophus was shrewd, meticulous, and devoted to his brother’s success: “He never forgot his zeal for duty, even at the times which he devoted to pleasure,” Psellus says. “[N]othing ever escaped his notice…. [E]veryone feared him and trembled at his superintendence.”

5

Under John’s guidance, Michael began to hem Zoe in, reducing her influence at court. He confined her to her chambers and ordered that anyone visiting her had to be cleared by her honor guard. Meanwhile, he had also stopped sleeping with her; his epilepsy had grown worse, and he had become impotent. Zoe fought back in the only way she could; now well into her fifties, she began an affair with another younger man, a bureaucrat named Constantine Monomachos who had just entered his thirties.

Michael IV was annoyed enough by this to exile Constantine Monomachos to the island of Lesbos, the traditional exile-spot for malfeasants. But Constantine Monomachos was hardly Michael’s greatest problem. The epileptic attacks were coming more frequently, often in full view of Michael’s subjects; he could no longer go out in public without a band of attendants, who would circle him, if he fell into a seizure, so that no one could see his convulsions.

John Orphanotrophus took steps to preserve the family’s power; he suggested that Michael adopt as his son and heir their twenty-five-year-old nephew (their older sister’s son), also named Michael. The adoption was completed in 1040. By the middle of 1041, Michael IV was barely able to walk: “The power of nature could not be mastered,” Psellus writes, “nor could the emperor vanquish and overwhelm this disease for ever. Secretly and step by step it advanced to the final dissolution.” He died in December, aged thirty-one, and his nephew was crowned as Michael V in his place.

6

Michael V was anxious to shake off the control of his powerful uncle. Once he was on the throne, he ordered both his uncle and his adoptive mother Zoe banished. He had overestimated his authority, though. John Orphanotrophus was respected, if not particularly popular, but Zoe, still beautiful, charismatic, and badly treated, was loved: “The indignation was universal, and all were ready to lay down their lives for Zoe,” Psellus says. He was actually in Constantinople at the time of the riot, and describes mobs in the streets armed with axes, broadswords, spears, and stones, ready to kill Michael V as soon as he showed his face.

7

In disguise, Michael sneaked down to the port and set sail for a nearby monastery. He took refuge in the church there, clinging to the altar. The mob followed him, dragged him away, and blinded him with a sharp iron. They left him there and returned to the city, where Zoe and her sister Theodora were acclaimed as co-empresses. “So the Empire passed into the hands of the two sisters,” Psellus says, “and for the first time in our lives, we saw the transformation of the women’s quarters into an emperor’s council chamber.”

8

Zoe, now sixty-three, recalled from exile and married her young bureaucratic lover, Constantine Monomachos, and had him crowned as emperor—the third man to gain his power through marriage to her. It was an impressive career for an eleventh-century woman. Even in her sixties, she remained attractive. “She had golden hair, and her whole body was radiant with the whiteness of her skin,” writes Michael Psellus, who saw her himself. “There were few signs of age in her; in fact…you would have said that here was a young woman, for no part of her skin was wrinkled, but all smooth and taut, and no furrows anywhere.” The golden hair undoubtedly owed something to art—Psellus adds that she kept an entire chamber stocked with lotions, creams, and other beauty aids—but Zoe was apparently gifted with amazingly good genes.

9

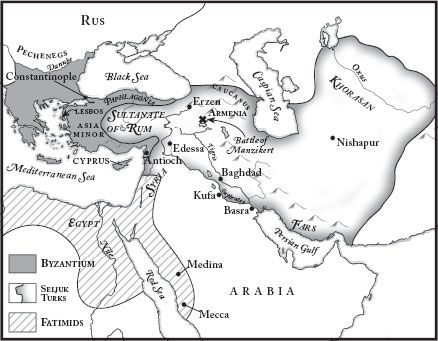

The men who ascended to power with her help were not as lucky. Constantine Monomachos now found himself at the head of an empire threatened on almost every side by outside powers. The personal had taken center stage at court for too long; Byzantium had begun to slip, little by little, from the heights that Basil II had attained. Constantine Monomachos was forced to deal with a rebellion by one of his generals, an attack from the Rus, a migration of Pecheneg refugees across the frozen Danube, and hostile Muslim forces to the east. He coped with these problems one by one, but in 1048, six years after his coronation, he came face to face with an enemy he could not conquer.

10

T

HE ENEMY WAS

T

OGRUL

, the Turkish chief who had led his coalition in the conquest of the Ghaznavid lands west of the Indus mountains. Togrul had now been at the head of his tribe, the Seljuq Turks, for twenty years. They were, in the words of historian René Grousset, “a horde without tradition, and the least civilized of all the nomad clans,” but Togrul had provided them with a path into nationhood. He had himself crowned sultan of the Turks in 1038 and had established his capital at Nishapur. His Turks were now strong enough to challenge Byzantium.

11

The first Turkish raid into Byzantine territory came in 1046; it was only a tentative prod at the Byzantine borders, and the Turks who came into Armenia withdrew without causing any real damage. But in 1048, a much larger Turkish army breached the eastern border and captured the rich border city of Erzen. Constantine Monomachos sent an army of fifty thousand to drive the invaders back; in a sharp nasty battle on the city’s plain, the Byzantine soldiers were badly defeated. The Seljuq Turks took thousands of prisoners, with the Byzantine commanding general among them, and captured the army supplies as well: thousands of wagons filled with food, dry goods, and money.

12

Constantine Monomachos decided to make a treaty with the Seljuq Turks instead of continuing to fight. In exchange for peace and the return of the captives, he agreed to give up some of the land on the eastern frontier. He also sent expensive gifts to Togrul and promised that he would allow Muslims to worship freely in Constantinople; the Turks had converted to Islam, and this was a gesture of friendship. Togrul accepted the terms and sent Constantine’s commander back to Constantinople unharmed.

For the moment, fighting was over. But the treaty was a devil’s deal. Like every emperor since Basil II, Constantine Monomachos’s biggest concern was surviving as emperor; fighting to keep the throne he had married, rather than inherited, absorbed him. As he held onto the empire, it shrank in his hands like a treasured and much-guarded balloon.

He was also ill. He had suffered for some time from a disease that racked him with painful muscle convulsions and slowly paralyzed him. “His fingers…completely altered from their natural shape, warped and twisted with hollows here and projections there,” Psellus writes. “His feet were bent and his knees, crooked like the point of a man’s elbow.” He was forced to give up first riding and then walking. Breathing became difficult; talking caused him pain; beating off the Turks must have seemed entirely impossible.

13

Soon the problem of the Turks passed to the next generation. Zoe died in 1050 at seventy-two, still wearing thin dresses and presiding as the great beauty of Constantinople. The much younger Constantine Monomachos followed her in 1055; the elderly Theodora, left alone on the throne, died in 1056. Before her death she declared that the throne should pass to her trusted minister Michael Bringas, a man who was not much younger than she, and who instantly was nicknamed “Michael Gerontas,” or “Michael the Aged.”

Meanwhile Togrul was closing his grip tightly around the Muslim lands to the south. The Buyid dynasty, much weaker than it had once been, still controlled Baghdad; in 1056, as Michael the Aged was ascending to the throne in Constantinople, Togrul marched into Baghdad and removed it firmly from Buyid control, driving the last Buyid rulers into exile. The Abbasid caliph still lived in Baghdad. He still retained some spiritual authority, although not a shred of political power, and Togrul made a deal with him. The caliph could remain peacefully in Baghdad as long as he agreed to recognize Togrul as supreme sultan, highest authority in the Muslim world, in the Friday prayers. Once, the mention of anyone other than the caliph or his heir in the Friday prayers had been tantamount to treachery. Now the caliph himself would pray for the sultan. In the Abbasid realm, the divorce between political and spiritual power was complete.