The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (79 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

The Scots, like the English, retained the right to accept or reject their kings. In 1040, Mac Bethad declined to pay the taxes that subject kingdoms yielded to the high king. Duncan marched into Moray to collect the payment by force. In the battle that followed, Duncan was killed. His widow fled from Scotland with her two children; Mac Bethad claimed the high kingship of Scotland and refused to yield to the Danish king in the south.

Before he could march to the north and fight against the Scots, Harold Harefoot—halting for a night in Oxford, during a royal progression south—grew ill and died. At once, Harthacanute made for England’s shores. He arrived with sixty ships, was welcomed as the new king of England and Denmark, and immediately made himself unpopular. “He started a very severe tax that was endured with difficulty,” the Chronicle says, “and all who hankered for him before were then disloyal to him.” He didn’t improve his position by ordering Harold Harefoot’s body dug up and flung into a swamp, or by sending his soldiers to collect the severe tax by force when the people of western Mercia were unable to pay it.

13

Fortunately, the English did not have to suffer under his reign for long. Less than two years later, Harthacanute was giving the toast at a wedding when he had a convulsion and fell down dead. It is impossible to know whether he had a stroke or whether the wine in his cup was less than wholesome; in any case, his death left the throne of Denmark open (it was claimed almost at once by Magnus the Good, who united Norway and Denmark under his rule), and it opened the way to the English throne for the last living son of Ethelred the Unready.

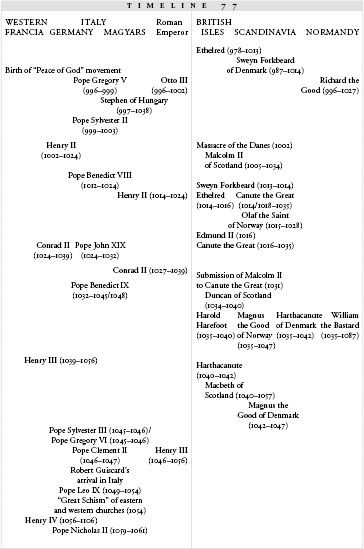

Between 1042 and 1066, Earl Godwin fails to put his sons on the throne, Halley’s Comet passes overhead, and William of Normandy conquers England

E

DWARD WAS NOW

thirty-eight, his personality permanently stamped by his early life. Before his twelfth birthday, his father had died, his mother had married a man who wanted to kill him, and he had been sent away to live in a country whose language he did not know. He was a withdrawn and silent man, known for piety (his devotion earned him the nickname “Edward the Confessor”) but nevertheless hard and unforgiving. The witan acclaimed him as king, and as soon as he was in possession of the throne he ordered that all of his mother’s worldly goods be confiscated: “He took from his mother whatever gold, silver, gems, stones, or other precious objects she had,” writes the chronicler John of Worcester, “because…she had given him less than he wanted.” Hatred had been nursed within him for so many years that he could not let it go, even when the crown was his.

1

Edward soon discovered that the throne was shaky beneath him. By this time, the earls who ruled the four earldoms of England practically controlled the decisions of the witan; they had gained so much power that no king could stay in power without their assistance, and Godwin, the Anglo-Saxon weathercock, was the strongest of them all. In fact, William of Malmesbury says that Godwin told the king as much: “My authority carries very great weight in England,” Godwin says, in Malmesbury’s

Gesta Regum Anglorum

, “and on the side which I incline to, fortune smiles. If you have my support no one will dare oppose you, and conversely.”

2

Godwin probably never said anything quite so explicitly threatening, but Edward certainly understood the old earl’s power. In 1045, the king ensured himself of Godwin’s goodwill by marrying Godwin’s daughter Edith and giving Godwin’s son Harold the title of “Earl of East Anglia.” The Godwin family now controlled two of the four earldoms as well as occupying the king’s bedchamber; and old Godwin himself undoubtedly hoped that his daughter would give birth to the next king of England.

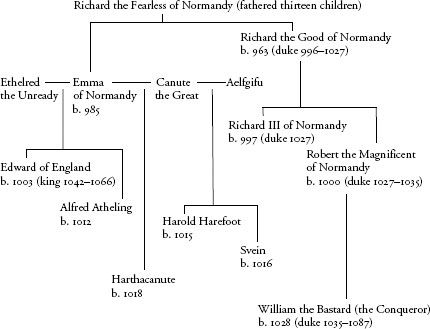

78.1: The English and Danish royal families.

But it seems likely that the marriage was never consummated. Edward was irretrievably celibate: the iron self-possession that had walled him off and protected him during his horrible childhood never allowed him to share his body with another, male or female. Nor was he particularly fond of Edith, who was a political pawn in the game he was playing with Godwin. He married her, says Henry of Huntingdon, “under obligation for his kingdom to the powerful Earl Godwin,” and he never forgot it. (Another chronicler says that those who saw the new queen were struck, simultaneously, by her learning and her “lack of intellectual humility and of personal beauty.”)

3

And he had still not resigned himself to Godwin’s control. Over the next seven years, Edward worked unceasingly to gain the loyalty of the other two earls, Leofric of Mercia and Siward of Northumbria. Both saw advantage for themselves in getting rid of the leechlike Godwins. By 1051, Edward felt secure enough to exile Godwin, Harold, and all the rest of the family. He sent Edith to a nunnery, reclaimed Wessex as a royal possession, and gave young Harold Godwin’s earldom of East Anglia to Leofric’s son; Siward was rewarded for his support with treasure and a bishopric.

4

Old Godwin went to Western Francia, but he refused to accept his exile. He was, says John of Worcester, “a man of assumed charm and natural eloquence in his mother tongue, with remarkable skill in speaking and in persuading the public to accept his decisions.” Now he collected his supporters, sailed up the Thames before Edward could assemble a fleet to keep him out, and made his case directly to the people. “He met the London citizens,” says John of Worcester, “some through mediators, some in person…and succeeded in bringing almost everybody into agreement with his desires.” By this time, Edward’s armed forces had gathered, but they were reluctant to go against public opinion: “Almost all were most loath to fight their kinsmen and fellow countrymen,” John says. “For this reason, the wiser on both sides restored peace between the king and the earl.”

5

Edward had been outmaneuvered. He backed down, in the face of the overwhelming support that Godwin had managed to whip up, and restored the old man to the position of Earl of Wessex. He was also forced to bring Edith back from her nunnery, and to take East Anglia away from Leofric’s son and give it back to young Harold Godwinson.

Old Godwin did not last much longer; he died of a stroke on Easter Monday of 1053 and was buried with great honors. But by then, young Harold had displayed his father’s talent for engaging popular support. He was well liked, charming, and a good administrator; and Edward, once again giving way to public sentiment, awarded Godwin’s old position of earl of Wessex to his son.

The other earls clung to their power in the face of Godwin’s maneuvering. In 1054, Siward of Northumbria won particular renown by marching north, confronting the Scots, and killing the high king Mac Bethad in battle; the Scots were once again forced to swear loyalty to the king of England. But Harold Godwinson matched old Siward’s accomplishment by marching west and fighting against the rebellious Welsh, forcing

them

to swear submission just as the Scots had.

By 1057, Harold and his Godwin brothers held three of the four earldoms of En gland.

*

Harold, the oldest and most powerful brother, soon proved that he had as much power as the king. When his brother Tostig, earl of Northumbria, began to persecute the taxpayers of Northumbria by raising the rates and then sending soldiers to collect the money, Harold took charge of disciplining him—normally the prerogative of the monarch. He marched against Tostig’s soldiers with his own forces, defeated his brother, and forced him to leave England. Tostig fled to Norway and took refuge at the court of Harald Hardrada, king of Norway, who had followed Magnus the Good to the throne. There, Tostig simmered in fury, waiting for revenge.

A series of unexpected events soon gave him the chance to wreak it.

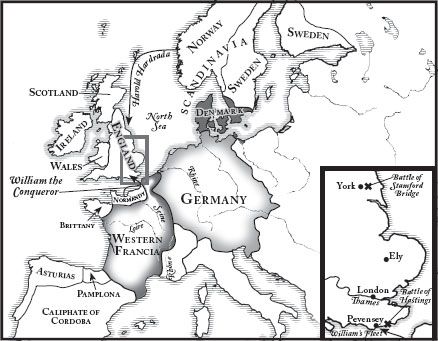

The first happened sometime in 1064, when Harold Godwinson ran into fairly routine trouble at sea. He was sailing in the English Channel when a storm caught him and drove him eastward until his ship came up onto the shores of Normandy. Without ship, men, or money, he was forced to appeal to William the Bastard, duke of Normandy, to provide all three so that he could get home again.

By this time, the chaos in Normandy had resolved itself. Emma’s bastard great-nephew William, who had become duke at the age of eight, had grown into a man and had put down the rebellion in his dukedom with a firm hand. By 1064 he was thirty-six years old with the military experience of a soldier twice his age.

We have no way of knowing exactly what passed between the two men. There are, as historian David Howarth points out, nine different versions of the encounter, with English, Norman, and Danish chroniclers telling different stories about what Harold promised to William in order to get home again. All we can say for certain is that by the time Harold left Normandy, William the Bastard was determined to become the next king of England. Edward the Confessor was just past sixty and clearly uninterested in fathering an heir; William, his first cousin once removed, was his closest adult male relative. Harold’s father Godwin had been a kingmaker; Harold Godwinson could help William gain the favor of the English nobility.

But he could not promise much more. The crown was not his (or anyone else’s) to give away. It lay in the gift of the witan.

6

In any case, William gave Harold Godwinson men and ships and sent him back to England. A little more than a year later, during the Christmas festivities of 1065, Edward the Confessor fell ill. He died on January 5, 1066, and was buried the next day in Westminster Abbey, which had just been finished. On the very same day, just as soon as the coffin was out of sight, the witan met and chose Harold Godwinson to be the next king of England.

He was not the only choice. Edward the Confessor had, some years before, retrieved Edmund Ironside’s grandson from Hungary; the toddler son of the king, who had been saved from death by the king of Sweden and fostered by strangers in Hungary, had married a Hungarian wife and fathered a son named Edgar. Edward the Confessor had brought Edgar back to England and was raising him as an adoptive son.

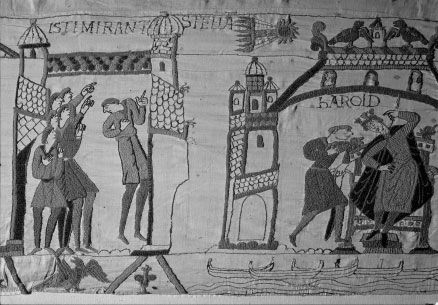

78.2: Detail from the Bayeux Tapestry, showing bystanders pointing at Halley’s Comet as it passes overhead, with Harold and attendant on the right

Credit: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

But Edgar was only fourteen years old and essentially a foreigner. The witan preferred a grown-up, one who had already proved himself in battle; the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

suggests that Edward himself, on his deathbed, had recommended that Harold follow him to the throne. So Harold Godwinson was declared Harold II of England in Westminster Abbey, the first monarch to be crowned there.

At once William the Bastard began to prepare an invasion. Winds and tides held him off for the time being, but Harold knew that the Norman duke was on his way. Sure that the Normans would attack in the spring, when the weather allowed, he assembled a standing army and kept them encamped, on high alert. A dreadful sign in the heavens, during the last week of April, confirmed that a great threat was approaching. It was, the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

says, “a sign such as men never saw before…a haired star.” The elliptical orbit of Halley’s Comet had brought it into sight of England, where it burned in the skies for a full week.

7

But by the end of August, Harold had begun to relax his guard. The English army and navy had been waiting for months: “all the summer and the autumn; and a land-army was kept everywhere by the sea…. When it was the Nativity of St. Mary, the men’s provisions were gone, and no one could hold them there any longer. Then the men were allowed to go home, and the king rode inland, and the ships were sent to London.”

8

78.1: The Battle of Hastings

The feast of the Nativity of St. Mary was on September 8, and it was perfectly reasonable for Harold to conclude that no one was coming. Sailors stayed off the sea during the fall and winter, fearing the same high winds that had driven Harold onto the shores of Normandy two years earlier. But just as Harold was returning to London, ready to take up the task of governing his country, two things happened. His brother Tostig, whose anger had tipped over into obsession, had finally convinced Harald Hardrada of Norway that England would reject Harold Godwinson and rally to his banner as soon as he landed on England’s shores. The two men had recruited men and ships from the unhappy Scots. They were keeping a close eye on the troop movements in the south, and when the English camps began to break up for the winter, the joint Norwegian and Scottish expedition began to move towards invasion.

9