The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (80 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

At the same time, and apparently by sheer chance, William the Bastard lost patience. He was tired of waiting for good winds. Late in the second week of September, he launched his attack fleet into the English Channel, where they were promptly battered by an enormous storm that sank some of his ships, blew others off course, and drowned part of his invasion force. Harold of England knew nothing of the struggle offshore. He was in London when he heard horrible news from the north: Harald Hardrada and Tostig had landed near York, with Harald’s black-raven banner flying above them. A hastily assembled English army had marched out to meet them and had been slaughtered. York had agreed to a formal surrender, complete with hostages, to be carried out on September 25.

10

In a superhuman effort, Harold rounded up the dispersing soldiers and left London. They reached York on the morning of the planned surrender. Harald and Tostig rode to the agreed-upon meeting place, Stamford Bridge, to find the king of England and his army waiting in place of the cowed citizens of York and their chosen hostages.

Both armies drew their swords at once. Henry of Huntingdon gives us a vivid picture of the battle: “It was desperately fought,” he says,

the armies being engaged from daybreak to noonday, when, after fierce attacks on both sides, the Norwegians were forced to give way…. Being driven across the river, the living trampling on the corpses of the slain, they resolutely made a fresh stand. Here a single Norwegian, whose name ought to have been preserved, took post on a bridge, and hewing down more than forty of the English with a battle-axe, his country’s weapon, stayed the advance of the whole English army till the ninth hour. At last some one came under the bridge in a boat and thrust a spear into him through the chinks of the flooring.

11

The English army advanced across the bridge and slaughtered the remnants of the Norwegian force. Both Harald Hardrada and Tostig were killed in the fighting; Harold II received the Norwegian surrender from Harald’s son and allowed the young man to go home. He took with him the remnants of the Norwegian force: twenty-four ships, out of an invasion force of more than three hundred.

Harold’s hard-won victory had just lost him his kingdom. He went into York with his men, to provision and rest them for the journey home. They were still in York when another messenger arrived with even worse tidings. A few days earlier, William the Bastard had landed at Pevensey, on the southern coast, and there were at least eight thousand men with him, even after the battering from the channel storms.

Harold hurried his damaged, weary, footsore army on yet another forced march. They arrived in the south of England on October 5, and Harold at once sent ambassadors to William to attempt to resolve the situation without further fighting. William was unyielding. He insisted that Edward the Confessor had intended

him

to receive the crown of England, and he further accused Harold of swearing a sacred oath, after that shipwreck in Normandy, to hand over the throne to William.

A week of fruitless negotiations made it very clear that William would not leave without a fight. On October 14, the English army—mostly foot-soldiers—met the Norman force of cavalry, infantry, and archers near the town of Hastings. They were killed in droves. Later stories embroider the Battle of Hastings with multiple details, but the oldest account, in the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, is brief and stark. “King Harold gathered a great army, and came against him at the grey apple-tree,” it reads, “and there was a great slaughter on either side. There were killed King Harold, and Earl Leofwine his brother, and Earl Gyrth his brother, and many good men. And the French had possession of the place of slaughter.” By day’s end, every Godwin man was dead, and William the Bastard had become William the Conqueror.

There was one heir left in the English line—fourteen-year-old Edgar, still in London. In a last act of defiance, the witan met and crowned him as king. Edgar was young but not stupid. He escaped from his honor guard, got to William, and surrendered as quickly as possible. William sent the boy back to Normandy and ordered him to be treated well. “And then William came to Westminster,” says the

Chronicle

, “and the Archbishop consecrated him as king.”

12

He was now William I, properly crowned in Westminster Abbey. The English struggle against the Vikings had ended; by way of France, a Viking king finally had full possession of the English throne.

Between 1016 and 1108, the Caliphate of Cordoba disintegrates, the northern Christian kingdoms battle with each other, the Muslim Almoravids cross over into Spain, and El Cid accidentally creates an oasis of tolerance

I

N 1016, THE

C

ALIPHATE OF

C

ORDOBA

—which had risen to a sudden and dizzy height of magnificence—paused at the edge of the crest and then plummeted downwards. The caliph Sulayman II was captured and put to death by his rivals for power, and the caliphate itself began to split apart.

The catastrophe of 1016 can be traced back forty years, to the same man who led the caliphate into magnificence: Muhammad ibn Abi Amir, known more widely as al-Mansur, “The Victorious.” In 976, the young caliph Hisham II had inherited the rule of Cordoba on the death of his father. Hisham II was only ten years old, which opened the caliphate up to control by his ministers; and of these, al-Mansur was the most ambitious. He had arrived in Cordoba some years earlier, travelling from his home on the southern coast, and had devoted himself to the study of law—and the task of rising up through the ranks of civil service. “Despite his humble antecedents,” wrote the eleventh-century chronicler Abd Allah, “he achieved great things, thanks to his shrewdness, his duplicity, and his good fortune.”

1

Al-Mansur, who was around forty when Hisham II became caliph, saw the child’s rule as his chance to grasp power. In 978, through a combination of persuasion and threat, he had himself appointed vizier to the little boy—prime minister and household administrator rolled into one.

At once he ordered construction of a new palace. When it was finished, in 981, he moved himself and the entire bureaucracy of Cordoba into it. Hisham II, now fifteen, was left in the caliph’s palace alone, without daily contact from any of his ministers or courtiers. Al-Mansur announced that the boy had decided to devote himself to good works, and kept him isolated. At the same time, the vizier accused of heresy and disloyalty other high officials who might also aspire to power, and had them exiled or put to death. “His pretext,” Abd Allah says, “was that their survival would have led to much discord and dissension and culminated in the ruin of the Muslims.” His name was now spoken, along with the caliph’s, in Friday prayers—proof that he had risen to the top of the palace hierarchy.

2

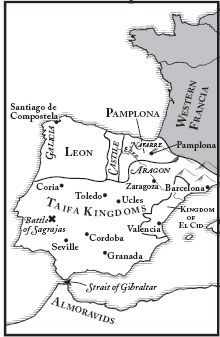

Al-Mansur may have been ruthless, but he was also an excellent strategist and administrator. He reinforced the Cordoban army with crowds of Berber soldiers, brought over from North Africa, and during his rule as vizier, the Caliphate of Cordoba triumphed in battle after battle against the Christian kingdoms to the north. Barcelona, which had been governed by independent Christian dukes for over a century, was sacked in 985. The king of Pamplona, Sancho II, suffered a series of humiliating defeats and finally came to Cordoba to make peace—which al-Mansur accepted, along with Sancho’s daughter as his wife. In 999, the caliph’s armies flooded over the border of the Kingdom of Leon and destroyed much of the city of Santiago de Compostela, which was doubly embarrassing because it was not only Christian territory but also a site of pilgrimage for Christians from all over the world; the bones of the apostle James, the disciple of Jesus, were said to rest in its cathedral.

3

In all, al-Mansur was said to have won fifty-seven battles over the northern resistance: “He gained decisive victories over the enemy,” Abd Allah concluded, “and during his time, Islam enjoyed a glory which al-Andalus had never witnessed before, while the Christians suffered their greatest humiliation.” Under his capable and unforgiving rule, al-Andalus prospered, even with the rightful caliph under house arrest.

4

But the rapid expansion had driven the Muslim kingdom on the peninsula past the place where its underpinnings could support it. Beneath the surface triumphs, the foundations were beginning to disintegrate.

When al-Mansur died in 1002, his son Abd al-Malik was forced to fight continuously to keep the borders of the caliphate out to where al-Mansur had pushed them. He claimed the post of vizier, as though it had become hereditary; and he too kept Hisham away from any involvement in government. But he spent the six years of his caliphate at war and did little governing himself. During the dank cool October of 1008, he was campaigning in the north against the Christian region of Castile when he caught a chest cold. He had always had weak lungs, and the cold turned into a cough that killed him.

5

Now the decay that al-Mansur’s glorious victories had whitewashed began to show through. Al-Malik’s brother, al-Mansur’s younger son Abd al-Rahman, saw no reason to keep on hiding his power beneath the umbrella of a legitimate caliph. To be ruler in all but name didn’t suit him; he wanted the name as well. He forced Hisham II (now in his forties) to name him heir to the caliphate.

This would have brought a final end to the Umayyad hold on the caliphate in Cordoba, and the other members of the Umayyad family—who already resented the privileges claimed by al-Mansur and his family, and who particularly disliked the high position held by so many Berbers in the army, to the exclusion of Arab officers—revolted.

Unfortunately, they didn’t unify behind a single Umayyad candidate—some supported Hisham II, others wanted another Umayyad caliph to replace him—and a civil war broke out. Abd al-Rahman and his Berbers fought against the various Umayyad factions who wanted the caliphate back, and the Umayyads fought against each other. In the years of struggle that followed, both Abd al-Rahman and Hisham II were killed. Eventually, the Umayyad claimant Sulayman managed to beat back the opposition and become caliph, but he held the throne for only a handful of years.

The civil war had so fractured the kingdom that it was vulnerable to outside attack, but the attack didn’t come from the Christian kingdoms in the north. Instead, it came from a Berber soldier named al-Nasir, who in 1016 marched into Cordoba at the head of his own North African forces, took Sulayman II captive, and beheaded him in public with his own hands. He then proclaimed himself caliph in Cordoba. Sulayman’s head and the heads of the Berber chiefs who had fought against al-Nasir instead of joining him were then cleaned up, perfumed and preserved, and carried around al-Andalus by al-Nasir’s men, so that all could see the fate of those who opposed him.

6

Despite the show and tell, al-Nasir survived only two years before he was assassinated in his bath. The rot had set in to stay. After 1018, no caliph managed to rule in Cordoba for more than a few years, and few of the claimants died a natural death. In 1031, the last man to try to claim the title died, and al-Andalus fell apart into a fragmentation of little city-states. Their kings were called

reyes de taifas

, the “party kings,” each the head of his own tiny political movement. Some were Arab, others were Berber. Over the next half-century, over thirty of these

taifa

kingdoms would blanket the former territory of the caliphate.

7

T

HE NORTHERN

C

HRISTIAN KINGDOMS

had spent their entire existence defending themselves against the threat of the caliphate. Now, as the caliphate disintegrated, the Christians of al-Andalus were able to draw their eyes away from the Muslim south. They began, instead, to look at each other: no longer allies, but competitors.

The first aggressor in the north was the king of Pamplona, Sancho III (“the Great”), grandson of the king who had given his daughter in marriage to the vizier al-Mansur. His ambitions had begun to grow back in 1016. His territory already enfolded not only the fortress city of Pamplona (built by the tribe of the Vascones centuries earlier, and sacked by Charlemagne during his retreat from al-Andalus), but also the northern region known as Navarre and the rich upper valley of the Ebro river. As the caliphate to the south turned inwards and started to fracture, Sancho the Great cast a covetous eye on the neighboring Christian territory to his west: Castile, ruled by noblemen who called themselves counts, rather than kings. Sancho the Great began his takeover peacefully, by marrying the count’s daughter. The next year, when the count of Castile died, Sancho the Great offered to “protect” Castile on behalf of its new count: his young brother-in-law Garcia II, a child of three.

Becoming Castile’s regent gave Sancho the Great the opportunity to fold Castile into his territory, making Pamplona the largest northern kingdom. Alfonso V (“the Noble”), king of Leon, took notice. He made secret arrangements of his own to pull Castile back into his own orbit; when Garcia II reached the age of thirteen, Alfonso offered to betroth the young count to his own sister.

Sancho the Great, preserving appearances, agreed enthusiastically to the match—and announced that in order to do his brother-in-law honor, he and his entire army would accompany the boy to Leon for the formal celebration of the betrothal. No sooner had they arrived in Leon than three assassins, brothers from the Castilian family of Vela, attacked the boy and stabbed him to death in front of his sister, his brother-in-law, and their retinue. They then fled—into the kingdom of Pamplona.

8

This was enough to confirm that they were in the pay of Sancho the Great, but he was no fool; he had hired Castilians to preserve deniability, and when they took refuge in his own territory he sent armed men after them, arrested them, and burned them to death for murdering the count. If his young wife had suspicions about her husband’s role in her brother’s death, she never expressed them in public; she became countess of Castile, which meant that the kingdom had effectively been united with Pamplona.

The joint realm, increasingly known as the Kingdom of Navarre, now went to war with Leon. For the next six years, Leonese soldiers resisted the invasion of Sancho the Great’s armies; but the war ended in 1034, when Sancho drove the king of Leon out of his capital city and entered it in triumph. The exiled ruler retreated into the small territory of Galicia, where he was killed three years later.

Sancho the Great now controlled all three Christian kingdoms of the north, plus a few of the smaller regions. The conquered lands “submitted to his rule,” the official court history tells us, “because of his conspicuous integrity and virtue.” In fact Sancho had gained his kingdoms through ruthless war and manipulation, and ruled them without apology: the history concludes, “Because of the extent of the lands he possessed and ruled, he had himself called ‘emperor.’”

9

But the imperial title was merely that. Sancho still thought like a local ruler; instead of passing the entire realm on to his heir, he decreed that the lands would be divided among his four sons. He died in 1035 at the age of sixty-five, barely a year after adding

imperator

to his titles.

The Christian empire fell apart. His four legitimate heirs, along with a fifth illegitimate son, spent the next twenty years ravaging each other’s territory and fighting for dominance. Not until 1056 did peace descend over the north, and then only because all of the heirs but one were dead. The second-born son, Ferdinand, was the last man standing. He claimed his father’s lands for himself, along with the imperial title: Emperor Ferdinand I. Once again, the northern kingdoms were one. The fragmentation in the south had allowed for the unification of the north: the Christian kingdoms of the peninsula, of

Spain

, had begun to take on a single identity, as the Muslim kingdoms of Spain had fallen apart.

79.1: Sancho the Great and the

Taifa

Kingdoms

But it was not a peaceful identity. Two decades of interfamily war had prevented Christian Spain from taking full advantage of the collapse to the south, and Ferdinand himself had built his empire on blood. He tried to wash away the stain with devotion: “King Fernando always used to see to it with special care,” says the twelfth-century

Historia Silense

, “that the better part of the spoils of his victories should be distributed among the churches and Christ’s poor, to the praise of that highest Creator who gave him victory…. [But] Fernando was still enmeshed in corruptible flesh and knew that he was not close to divine grace.”

10

When, in 1065, he felt himself fatally weakening and realized that his last illness was upon him, he took off his royal robes and crown and put on a hair shirt instead. He spent his last days in penance and died wearing the garments of a sinner.

He passed on both his empire and the tradition of civil war to his three sons. The oldest, Sancho II (“the Strong”), became king of Castile; his middle son Alfonso inherited Leon; and his youngest, the little territory of Galicia. But Sancho the Strong was unwilling to leave his brothers in peace. Accompanied by his right-hand man, the general Rodrigo Diaz, he began a war of reunification.

Rodrigo Diaz, better known by his nickname “El Cid” (Arabic for “The Lord”), was only in his early twenties at the time. But he had been a soldier since his early teens and was already experienced in battle. “King Sancho valued Rodrigo Diaz so highly,” writes El Cid’s biographer, “that he made him commander of his whole military following. So Rodrigo throve and became a most mighty man of war.”

11