The Hundred Years War (20 page)

Read The Hundred Years War Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

Henry’s army was recruited by the indenture system, captains being commissioned to hire men-at-arms and archers in specified numbers and at a stipulated rate. The first pay-packets were usually advanced by the captain, after which he was refunded by the exchequer who then supplied money for future payments ; generally the rate was the same as in Edward’s day. The bowmen’s equipment remained what it had been for a century, but the armour of the men-at-arms was very different from that worn at Crécy and Poitiers. For the last fifty years plate had been replacing mail to protect the wearer against arrows. It was still sur- . prisingly flexible as a man-at-arms fought more on foot than on horseback. But it was undeniably very heavy, weighing up to 661bs. English noblemen often imported these elaborate armours from Milan or Nuremburg. The wearers fought with weapons which smashed rather than cut or thrust—maces, battle-hammers and pole-axes. They no longer carried shields as they needed both hands for such tools.

In all Henry raised an army of about 8,000 archers and 2,000 men-at-arms, besides some unarmoured lancers and knifemen. They were supported by a large artillery train with sixty-five gunners, which had been in preparation for the last two years. Provisions, munitions, horses and ships were assembled on the same massive scale as the previous century. The King had a flair for logistics and personally supervised the operation ; to ensure fresh meat he had cattle and sheep driven to the ports on the hoof. Ships were supplied by the Cinque Ports or else hired or impounded, and eventually a fleet of 1,500 vessels assembled in the Solent. The flagship, the

Trinité

Royale, was no less than 540 tons and was manned by a crew of 300. Henry spent many weeks on the coast at Porchester Castle, organizing the entire embarkation with meticulous attention to detail and seemingly inexhaustible energy.

Trinité

Royale, was no less than 540 tons and was manned by a crew of 300. Henry spent many weeks on the coast at Porchester Castle, organizing the entire embarkation with meticulous attention to detail and seemingly inexhaustible energy.

During this time the Earl of March suddenly revealed a conspiracy to murder the King and replace him by the Earl himself, who was the son of Richard II’s heir presumptive. The ‘three corrupted men’ in this ‘Southampton Plot’ were Henry’s first cousin, the Earl of Cambridge, with Sir Thomas Grey, and the royal Treasurer Lord Scrope of Masham ; the Percys and the Lollard Sir John Oldcastle were also involved. In less than a week the three ringleaders had been beheaded. There was no further trouble.

On Sunday 11 August 1415, a bright sunny day, Henry V and his armada set sail. There was only a slight breeze so the voyage across the Channel took three days. Instead of landing at Calais as expected, the English landed in Normandy at the Chef-de-Caux on the Seine estuary, just outside the rich port of Harfleur. The King had told very few even of his closest advisers of the carefully chosen destination ; Harfleur was to be the base from which he would conquer Normandy and strike down the river at Paris. It would be another Calais but with shorter supply lines more suited to campaigning in the French heartland. However, Harfleur was not easy to capture. It had dauntingly strong walls with twenty-six towers and three mighty barbicans-fortified gateways, strengthened by drawbridges and portcullises-together with a deep moat. Its garrison, commanded by the tough and able Sieur d‘Estouteville, numbered several hundred men-at-arms. When Henry called on them to surrender to the rightful Duke of Normandy, he received a sarcastic answer-‘You gave us nothing to look after, so we’ve nothing to give you back.’

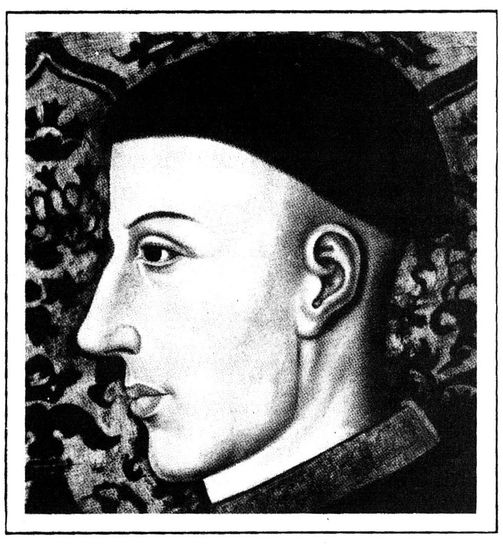

Sir Simon Felbrygg, KG, Richard II’s banner-bearer, who served with John of Gaunt at the relief of Brest; and his wife Margaret, daughter of Przimislaus, Duke of Teschen, and sometime maid-of-honour to King Richard’s queen, Anne of Bohemia. Brass of 1416 at Felbrigg, Norfolk.

The English built a ditch and a stockade all round the town, their ships guarding the estuary effectively cutting Harfleur off from any hope of reinforcements or revictualling. They began to mine the walls, but grew discouraged by the French skill at detecting their tunnels and counter-mining. Henry had to rely on his artillery. This included cast-iron cannon twelve feet long and over two feet in calibre, firing stone balls which weighed nearly half a ton and were capable of demolishing the strongest masonry—though sometimes they splintered, producing a primitive but viciously effective shrapnel. The trouble was to get them into position as the Harfleur garrison had guns too, mounted on the walls. The English built earthworks and dug trenches and slowly edged their cannon forward on clumsy wheeled platforms protected by thick wooden screens. They suffered considerably, but eventually positioned their guns which began to batter away at the walls ; often the King was up all night directing them. Sections of the walls began to collapse, crashing to the ground with a terrifying roar. Yet after a month the English had still failed to take what was only a small town, and partly because of the sweltering heat of high summer, partly because many of them had to sleep on marshy ground and partly through drinking bad wine and cider and contaminated water, dysentery and probably malaria broke out. Many died, including the Earls of Arundel, March and Suffolk and the Bishop of Norwich. ‘In this siege many men died of cold in nights and fruit eating; else of stink of carrions,’ says the chronicler Capgrave. But on 17 September a barbican fell to the English.

Inside the town the bombardment had demolished buildings and caused severe casualties, while food was exhausted ; no reply to desperate appeals for help had been received from the Dauphin and his advisers. On 18 September the garrison asked for a truce until 6 October, when they would surrender if they had not been relieved. Henry would only allow them until 22 September. No help came and on that day, a Sunday, Harfleur surrendered. After walking barefoot to the principal church to give thanks, the King expelled the inhabitants : ‘they put out alle the French people both man woman and chylde and stuffed the town with English men.’ The rich bourgeois were sent back to England to be ransomed, while 2,000 of the ‘poorer sort’ had to find their way to Rouen. Only a few of the very poorest were allowed to stay and these had to take an oath of allegiance.

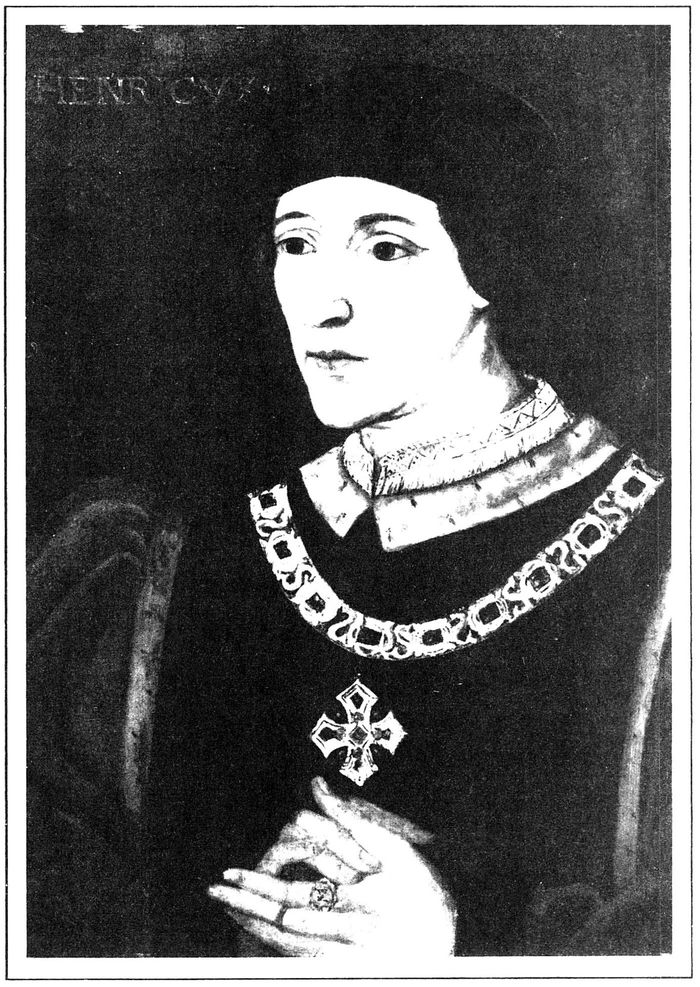

King Henry V (1387-1422)

‘Unto the French the dreadful judgement day

So dreadful will not be as was his sight.’

So dreadful will not be as was his sight.’

John, Duke of Bedford,

Regent of France (1389-1435)

Regent of France (1389-1435)

‘Give me my steeled coat,

I’ll fight for France.’

I’ll fight for France.’

King Henry VI (1421-1471)

Pale ashes of the House of Lancaster !

Thou bloodless remnant of that royal blood !’

Thou bloodless remnant of that royal blood !’

Although Henry had gained a useful new base in France, he had suffered disastrous losses ; about a third of his army were dead, either killed during the siege or from disease, while many of those still on their feet were ill. Besides sending his sick home, he had to leave a garrison. On 3 September he had written in a letter to Bordeaux that he intended to go down the Seine, past Rouen and Paris and then march to Guyenne, a journey of several hundred miles. His advisers convinced him that such a raid was now out of the question but failed to persuade him to return to England. The King insisted on a

chevauchée—he

would march the 160 miles to Calais. It was an odd decision ; perhaps he meant to demonstrate the inability of the French to harm their rightful sovereign chosen by God. On 6 October his troops began to leave Harfleur, the King and the Duke of Gloucester commanding the main army, Sir John Cornwall the advance guard and the Duke of York and the Earl of Oxford the rearguard. They abandoned their artillery and baggage-train, carrying provisions for only eight days, and they took these only because they expected to march through a devastated countryside. They did not foresee any opposition. Henry’s plan was simply to march north-east until the Somme was reached and then south-east down the river to the first undefended ford and, after crossing it, to make straight for Calais.

chevauchée—he

would march the 160 miles to Calais. It was an odd decision ; perhaps he meant to demonstrate the inability of the French to harm their rightful sovereign chosen by God. On 6 October his troops began to leave Harfleur, the King and the Duke of Gloucester commanding the main army, Sir John Cornwall the advance guard and the Duke of York and the Earl of Oxford the rearguard. They abandoned their artillery and baggage-train, carrying provisions for only eight days, and they took these only because they expected to march through a devastated countryside. They did not foresee any opposition. Henry’s plan was simply to march north-east until the Somme was reached and then south-east down the river to the first undefended ford and, after crossing it, to make straight for Calais.

The Dauphin’s forces had decided to intercept the English. An army many times larger assembled, gradually joined by such magnates as the Dukes of Orleans, Bourbon, Alençon, and Brittany, and even by John of Burgundy’s younger brothers, the Duke of Brabant and the Count of Nevers. The Dauphin himself was not allowed to take part. All brought splendidly equipped men-at-arms. It seems likely that Marshal Boucicault and his advance guard had linked up with the Constable d‘Albret and the main body at Rouen even before Henry had left Harfleur. It was all too easy for them to follow the English whose path was marked by blazing farmhouses—King Henry once observed that war without fire was like ‘sausages without mustard’.

We know a good deal about Henry’s

chevauchée

from the narrative of a chaplain who rode with his army. As they marched through the pelting rain the English did not at first realize that they were being pursued, but at ford after ford along the Somme they found their way barred by troops. Blanche Taque, Edward III’s ford, was defended by Boucicault in person. Furthermore the river was in flood. On 19 October Henry at last managed to cross, almost at the source of the Somme, by the two fords of Béthencourt and Voyennes near Peronne ; archers went over first at Béthencourt through water waist-deep, the men rebuilding the causeway which had been destroyed by the French ; while a similar operation was carried out at Voyennes. Enemy horsemen attacked but were beaten off, the crossings being completed shortly after dark. On 20 October French heralds arrived at Henry’s camp, bearing a challenge. ‘Our lords’, they told him, ‘have heard how you intend with your army to conquer the towns, castles and cities of the realm of France and to depopulate French cities. And because of this, and for the sake of their country and their oaths, many of our lords are assembled to defend their rights ; and they inform you by us that before you come to Calais they will meet you to fight with you and be revenged of your conduct.’ Henry replied simply : ‘Be all things according to the will of God.’ Adding that whatever happened he would march to Calais, he sent them away with a hundred gold crowns each. Accepting that he had been outmanoeuvred, the King at once ordered his men to take up positions—obviously he expected to be attacked at any moment. But there was still no sign of the French army.

chevauchée

from the narrative of a chaplain who rode with his army. As they marched through the pelting rain the English did not at first realize that they were being pursued, but at ford after ford along the Somme they found their way barred by troops. Blanche Taque, Edward III’s ford, was defended by Boucicault in person. Furthermore the river was in flood. On 19 October Henry at last managed to cross, almost at the source of the Somme, by the two fords of Béthencourt and Voyennes near Peronne ; archers went over first at Béthencourt through water waist-deep, the men rebuilding the causeway which had been destroyed by the French ; while a similar operation was carried out at Voyennes. Enemy horsemen attacked but were beaten off, the crossings being completed shortly after dark. On 20 October French heralds arrived at Henry’s camp, bearing a challenge. ‘Our lords’, they told him, ‘have heard how you intend with your army to conquer the towns, castles and cities of the realm of France and to depopulate French cities. And because of this, and for the sake of their country and their oaths, many of our lords are assembled to defend their rights ; and they inform you by us that before you come to Calais they will meet you to fight with you and be revenged of your conduct.’ Henry replied simply : ‘Be all things according to the will of God.’ Adding that whatever happened he would march to Calais, he sent them away with a hundred gold crowns each. Accepting that he had been outmanoeuvred, the King at once ordered his men to take up positions—obviously he expected to be attacked at any moment. But there was still no sign of the French army.

Other books

Witch Is Why Time Stood Still (A Witch P.I. Mystery Book 13) by Adele Abbott

Jugando con fuego by Khaló Alí

Last of the Red-Hot Riders by Tina Leonard

Solos by Kitty Burns Florey

Helpless by Daniel Palmer

Dawn by Tim Lebbon

Double Fake by Rich Wallace

Oscar and Lucinda by Peter Carey

The Navigator 2: We the People by Ben Winston

Appointment in Samarra by John O'Hara