The Hundred Years War (7 page)

Read The Hundred Years War Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

Modern research has revealed a far greater degree of sophistication in medieval logistics than one might expect from reading Froissart’s ‘honourable and noble adventures of feats of arms’. Even if most armies lived off the country, supply depots were needed while their troops were assembling. Victuals included salted and smoked meat, dried fish, cheese, flour, oats and beans, together with vast quantities of ale. These were gathered from all over England, usually by the sheriffs, and sent to the embarkation point in wagons along the rough, muddy roads, in barges down the rivers, or by sea—in the latter case on board commandeered ships. In addition there were fuel and munitions—among the latter being siege engines (springalds, arbalests, trebuchets and mangonels), weapons (especially bow-staves and arrows and bow-strings), gunpowder and shot. Huge numbers of horses were needed for such an expedition. The ships to transport them, and also the men and their supplies, were requisitioned by royal sergeants-at-arms, who ‘arrested’ them together with their crews, their original cargoes being compulsorily unloaded. The requisitioning took time and troops often had to wait at the ports for long periods before they could cross the sea.

On 13 July 1346 the English armada landed at La Hogue, on the north of the Cherbourg peninsula. As at D-Day in 1944, they were completely unexpected by the Normans, many of whose towns—as Godefroi d‘Harcourt had told Edward—proved to be unwalled. The following day the King launched a

chevauchée

through the Cotentin, deliberately devastating the rich countryside, his men burning mills and barns, orchards, haystacks and cornricks, smashing wine vats, tearing down and setting fire to the thatched cabins of the villagers, whose throats they cut together with those of their livestock. One may presume that the usual atrocities were perpetrated on the peasants—the men were tortured to reveal hidden valuables, the women suffering multiple rape and sexual mutilation, those who were pregnant being disembowelled. Terror was an indispensable accompaniment to every

chevauchée

and Edward obviously intended to wreak the maximum

‘dampnum’

—the medieval term for that total war which struck at an enemy King through his subjects. All ranks of the English army tasted the sweets of plunder. When Barfleur surrendered it did not escape from being sacked and burnt, ‘and much gold and silver was found there, and rich jewels : there was found so much riches, that the boys and villains of the host set nothing by good furred coats’. They then burnt Cherbourg and Montebourg and other towns, ‘and won so much riches that it was marvel to reckon on it’. A party of 500 men-at-arms rode off with Godefroi d’Harcourt for a distance of ‘six or seven leagues’ to lay waste and to plunder, and were astonished by the plenty which they found—‘the granges full of corn, the houses full of all riches, rich burgesses, carts and chariots, horse, swine, muttons and other beasts ... but the soldiers made no count to the King nor to none of his officers of the gold and silver that they did get’. The burgesses were probably sent back to England to be ransomed, a fate which seems to have been the lot of the entire town of Barfleur.

chevauchée

through the Cotentin, deliberately devastating the rich countryside, his men burning mills and barns, orchards, haystacks and cornricks, smashing wine vats, tearing down and setting fire to the thatched cabins of the villagers, whose throats they cut together with those of their livestock. One may presume that the usual atrocities were perpetrated on the peasants—the men were tortured to reveal hidden valuables, the women suffering multiple rape and sexual mutilation, those who were pregnant being disembowelled. Terror was an indispensable accompaniment to every

chevauchée

and Edward obviously intended to wreak the maximum

‘dampnum’

—the medieval term for that total war which struck at an enemy King through his subjects. All ranks of the English army tasted the sweets of plunder. When Barfleur surrendered it did not escape from being sacked and burnt, ‘and much gold and silver was found there, and rich jewels : there was found so much riches, that the boys and villains of the host set nothing by good furred coats’. They then burnt Cherbourg and Montebourg and other towns, ‘and won so much riches that it was marvel to reckon on it’. A party of 500 men-at-arms rode off with Godefroi d’Harcourt for a distance of ‘six or seven leagues’ to lay waste and to plunder, and were astonished by the plenty which they found—‘the granges full of corn, the houses full of all riches, rich burgesses, carts and chariots, horse, swine, muttons and other beasts ... but the soldiers made no count to the King nor to none of his officers of the gold and silver that they did get’. The burgesses were probably sent back to England to be ransomed, a fate which seems to have been the lot of the entire town of Barfleur.

On 26 July Edward’s army reached Caen, larger than any town in England apart from London, and soon stormed their way through the bridge gate. When the garrison surrendered, the English started to plunder, rape and kill, ‘for the soldiers were without mercy’. The desperate inhabitants then began to throw stones, wooden beams and iron bars from the rooftops down into the narrow streets, killing more than 500 Englishmen. Edward ordered the entire population to be put to the sword and the town burnt, ‘and there were done in the town many evil deeds, murders and robberies’—although Godefroi d‘Harcourt persuaded the King to rescind his order. The sack lasted three days and 3,000 townsmen died. One chronicler says that the English took ‘only jewelled clothing or very valuable ornaments’. The plunder was sent back to the fleet by barges. Edward seems to have done better than anyone: Froissart relates how from Caen the King ‘sent into England his navy of ships charged with clothes, jewels, vessels of gold and silver, and other riches, and of prisoners more than 60 knights and 300 burgesses’—the latter for ransom.

One of the prisoners was the Abbess of Caen, who must surely have complained that her captivity was against all the usages of Christian war. The King had issued the customary order to spare churches and consecrated buildings, but even so, nuns were raped and many religious houses suffered. The priory of Gerin was burnt to the ground and later the strongly defended monastery town of Troarn fell by storm.

Among the spoils of Caen was Philip VI’s

ordonnance

of 1339 for the invasion of England. Edward, who possessed an almost modern flair for propaganda, at once had copies made to be read in every parish church in England; in London, after a splendid pontifical procession, it was read at St Paul’s by the Archbishop of Canterbury ‘that he might thereby rouse the people’.

ordonnance

of 1339 for the invasion of England. Edward, who possessed an almost modern flair for propaganda, at once had copies made to be read in every parish church in England; in London, after a splendid pontifical procession, it was read at St Paul’s by the Archbishop of Canterbury ‘that he might thereby rouse the people’.

The English King then continued his march in the direction of Paris, still slaying and burning. He was able to pay his soldiers generously in addition to their loot, Jean le Bel tells us. The approach of the English was announced by flames in the distance and by mobs of terrified refugees. Philip massed as many troops as possible and sent reinforcements to Rouen—it seems likely he feared that if Edward captured the Norman capital he would control the lower Seine and be able to obtain fresh troops of his own from Flanders. Edward’s main objective had been achieved—to distract the French from Guyenne and Brittany, and lessen the pressure on Lancaster and Dagworth.

The English army finally stopped at Poissy, advance parties burning Saint-Cloud and Saint-Germain within sight of the walls of Paris. The English King had no intention of attacking the French capital—he had no proper siege train, and in any case his troops were hopelessly outnumbered by the vast army which Philip was assembling at Saint-Denis just outside Paris. The French had demolished all the bridges along that part of the Seine, hoping to trap the English. However, Edward managed to repair the bridge at Poissy over which he retreated northwards, destroying everything he could; at Mareuil he burnt the town, the fortress and even the priory. He next found his way barred by the river Somme, along which the bridges had also been broken down. Fortunately a local peasant showed him a sandy-bottomed ford just below Abbeville—‘the Passage of Blanche-taque’. The opposite bank was defended by several thousand enemy troops including Genoese crossbowmen, but after some volleys from their own archers the English forced their way across ‘in a sore battle’ : Philip was snapping at their heels and even captured some of their baggage, but luckily the river rose and prevented the French from crossing too.

Once over the Somme Edward thanked God. Although outnumbered he was no longer frightened of a battle—the way was now clear for him to retreat to Flanders if things went wrong. In any case a halt was essential, as his men were exhausted by their forced march; it is known that their food and wine, and even their shoes, were used up. Accordingly he camped on the downs near the little town of Crécy-en-Ponthieu.

The English King had found a perfect position, on rising ground. In front of him was the ‘Valley of the Clerks’, both his front and his right were protected by the little river Maie, while his flank was guarded by the great wood of Crécy which was ten miles long and four miles deep. The most obvious direction from which he might be attacked, the front, led up a downland slope which gave his archers an admirably clear field of fire. His army, now somewhat reduced, consisted of about 2,000 men-at-arms and perhaps 500 light lancers together with something like 7,000 English and Welsh bowmen and 1,500 knifemen—approximately 11,000 men, though estimates vary. The enemy was obviously near, so Edward drew up his troops in order of battle. On the right, on the slope above the Maie, he placed 4,000 men under the sixteen-year-old Black Prince (supported by such veterans as Sir Reynold Cobham, Sir John Chandos and Godefroi d’Harcourt). The centre of this division consisted of 800 men-at-arms on foot in a long line, probably six deep ; 2,000 archers were placed on the flanks—deliberately, so they could shoot at the French from the side when the latter attacked the centre—while behind these archers stood the knifemen. On his left Edward sited a second division, under the Earls of Northampton and Arundel, with 500 dismounted men-at-arms and 1,200 archers in the same formation as the division on the right. The archers of both divisions dug a large number of small holes, a foot deep and a foot square, in front of their positions in order to make the enemy horses stumble. Edward himself commanded the third division—700 men-at-arms on foot, 2,000 archers and the remaining knifemen—which he stationed somewhere behind to serve as a reserve.

Edward, having drawn up his army, says Jean le Bel, ‘went among his men, exhorting each of them with a laugh to do his duty, and flattered and encouraged them to such an extent that cowards became brave men’. He also warned them not to plunder the enemy wounded until he gave permission. ‘This done,’ adds the chronicler, ‘he allowed everyone to break ranks so that they could eat and drink until the trumpets sounded.’ (Large supplies of wine had been found at the nearby town of Le Crotoy by the quartermasters, while herds of cattle had been driven into the camp.)

‘Then’, says Froissart, ‘every man lay down on the earth and by him his helmet and bow to be the more fresher when their enemies should come.’ Meanwhile Edward established his command post at a windmill on the high ground on which his own division was stationed, from where he could see the entire battlefield. At noon news reached him that the French were coming up, whereupon he ordered the trumpets to sound and everyone rejoined his ranks.

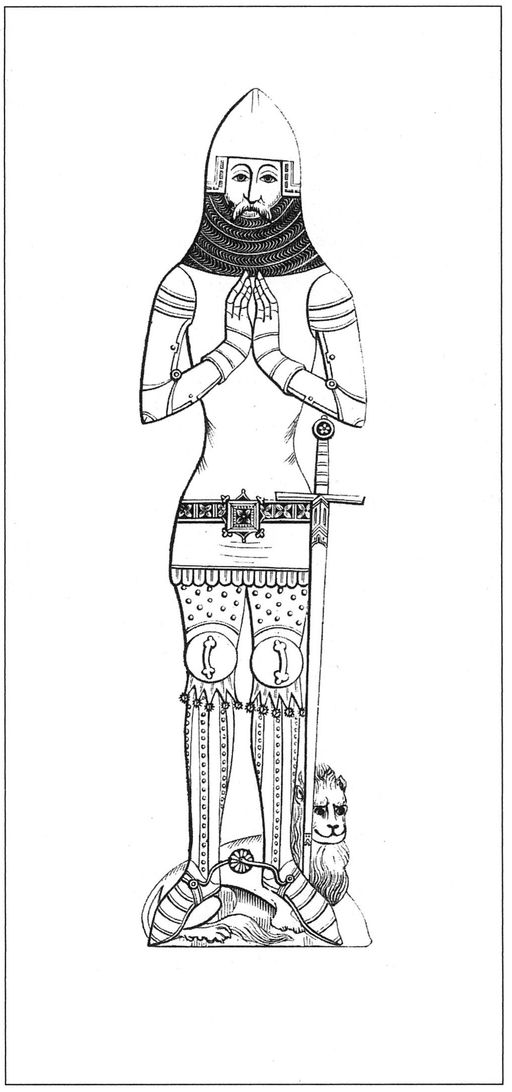

Thomas Cheyne, shield-bearer to King Edward III. He is wearing armour of a type that came in a few years after Crécy and stayed in fashion for the rest of the century, with a tight fitting cloth

jupon

over a steel breastplate on top of a chainmail shirt. Brass of 1368 in the parish church of Drayton Beauchamp, Buckinghamshire.

jupon

over a steel breastplate on top of a chainmail shirt. Brass of 1368 in the parish church of Drayton Beauchamp, Buckinghamshire.

It was Saturday 26 August 1346. King Philip, who had spent the night at Abbeville, had some reason to feel confident as his troops outnumbered Edward’s by nearly three to one—at least 30,000 including 20,000 men-at-arms. Unfortunately for Philip, when he rode out of Abbeville at sunrise after hearing Mass, his army was still arriving and it continued to do so throughout the day. With his usual caution the French King sent four men to investigate the enemy position. One, a knight called Le Moine de Bazeilles, reporting that the English were waiting in a carefully arranged order of battle, told Philip: ‘My own counsel, saving your displeasure, is that you and all your company rest here and lodge for this night for ... it will be very late and your people be weary and out of array, and ye shall find your enemies fresh and ready to receive you.’ The knight continued that next morning the King would be able to form up his troops and look for the right place to attack the English, ‘for, Sir, surely they will abide you’. Philip thought this excellent advice and gave orders for his troops to halt and make camp.

But there was always a problem in controlling excessively large medieval armies, and by now ‘the flower of France’ was completely out of control. While those in front tried to halt, the men-at-arms behind kept on coming and the front had to move on again. ‘So they rode proudly forward without any order or good array until they came in sight of the English who stood waiting for them in fine order, but then it seemed shameful to retreat.’ At the same time all the roads between Abbeville and Crécy were jammed with peasants and townsmen waving swords and spears, yelling ‘Down with them! let us slay them all !’ Eventually Philip, who was up in front, realized that he had lost any hope of restraining his troops. In desperation he ordered an attack—

‘Make the Genoese go on before, and begin the battle, in the name of God and Saint Denis.’ By then it was evening. The sun was beginning to set.

Trumpets, drums and kettledrums sounded, and a line of Genoese crossbowmen advanced to within 200 or even 150 yards of the English. As they did so they were drenched to the skin by a short but violent thunderstorm. At the same moment that they began to discharge their quarrels the English archers stepped forward and shot with such rapidity that ‘it seemed as if it snowed’. The Genoese had marched long miles carrying their heavy instruments, and it is probable that they had discarded the pavises or large shields which crossbowmen normally used to protect themselves while reloading. Highly vulnerable, they at once began to drop beneath the arrow-storm, which they had never before experienced. Tired, demoralized—even the setting sun, which had reappeared, was in their eyes—the survivors started running. This stage of the engagement may have lasted no more than a minute.

Other books

Lottery by Kimberly Shursen

Stand by Me by Neta Jackson

Finding Alice by Melody Carlson

Meet the Gecko by Wendelin van Draanen

Bad Girls, Bad Girls, Whatcha Gonna Do? by Cynthia Voigt

Butcher Bird by Richard Kadrey

Out of Focus (Chosen Paths #2) by L. B. Simmons

A Festival of Murder by Tricia Hendricks

Spiraling by H. Karhoff